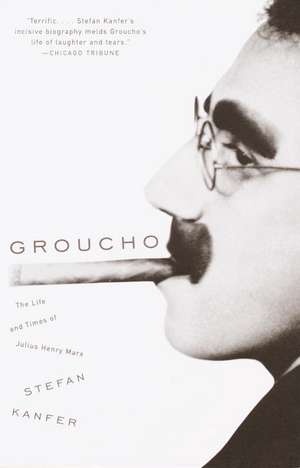

Groucho: The Life and Times of Julius Henry Marx

Autor Stefan Kanferen Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 apr 2001

Here is the amazing career of the man the world recognized as Groucho: the improbable disasters of the vaudeville years; the Marx Brothers, an act so funny W.C. Fields refused to follow it; the unprecedented Broadway success of The Cocoanuts and Animal Crackers; the cinematic triumphs of Duck Soup and A Night at the Opera; and the marvelous come-back career as king of the game show hosts with You Bet Your Life. Here, too, is the man himself: a lonely middle child who aspired to be a doctor; a man who sabotaged three marriages; a father alternately indulgent and cruel. Intelligent and thorough, hilarious and sad, Groucho is a spectacular biography of the century’s most influential comedian.

Preț: 126.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 190

Preț estimativ în valută:

24.24€ • 25.36$ • 20.13£

24.24€ • 25.36$ • 20.13£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 03-17 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375702075

ISBN-10: 0375702075

Pagini: 498

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE PHOTO INSERTS (34 HALFTONES)

Dimensiuni: 132 x 202 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0375702075

Pagini: 498

Ilustrații: 2 8-PAGE PHOTO INSERTS (34 HALFTONES)

Dimensiuni: 132 x 202 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.45 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

Stefan Kanfer's books include The Eighth Sin, A Summer World, The Last Empire, and Serious Business. He was the primary interviewer in the Academy Award-nominated documentary The Line King. A former writer and editor at Time and a Literary Lion of the New York Public Library, he has been a writer-in-residence at the City University of New York, the State University of New York at Purchase, and Wesleyan University. He lives in New York and on Cape Cod.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Introduction

On the night of May 21, 1972, a frail, bald, eighty-two-year-old trouper enters from the wings of Carnegie Hall and takes center stage. He has not performed in New York for some fifty years, and in that time he has risen to the status of pantheon figure. He has been on the cover of Time twice. Scholars have written Ph.D. theses about his humor; his remarks have appeared in H. L. Mencken's The American Language, as well as in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations and The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Whatever awards broadcasting has to offer he has won. He has been impersonated by George Gershwin, made the subject of a Broadway musical, feted in London and Paris. The French government has just invited him to Cannes, where he is to be made Commandeur dans l'Ordre dès Arts et dès Lettres.

Ticket holders have become used to him as an ageless two-dimensional black-and-white figure. They have to get used to him as a man -- especially this man. For arthritis and small strokes have made his missteps a parody of the old choreography, and his rheumy eyes can barely decipher the cue cards. All the same, he seems to occupy the entire hall, and 2,800 onlookers, some of them sporting clawhammer coats, greasepaint moustaches, and oversize cigars in homage to the speaker's signature costume, rise to their feet and applaud for nearly five minutes. Groucho Marx is no longer in full control of his body or his memory, but his fans have decided that these infirmities are irrelevant and unworthy of comment. As he sings and reminisces in a broken voice, senior members of the audience look past old age to see the springy vaudevillian of their youth, playing straight man to his brother in a schoolroom routine:

What is the shape of the world?

I don't know.

Well, what shape are my cufflinks?

Square.

Not my weekday cufflinks. The ones I wear on Sundays.

Oh. Round.

All right, what is the shape of the world?

Square on weekdays, round on Sundays.

What are the principal parts of a cat?

Eyes, ears, neck, feet.

You forgot the most important. What does a cat have that you don't have?

Kittens.

Middle-aged fans are more familiar with his celebrated stage lines, supposedly launched when one of his brothers tried to throw him off stride:

The garbage man is outside!

Tell him we don't want any.

I'd like-a to say goom-bye to your wife.

Who wouldn't?

In their minds the past fuses with the present, and they recall the outrageous comedian of some forty years before capering in films, walking on half-bent knees and waggling his expressive eyebrows as he insults plutocrats, pursuing or insulting Mrs. Upjohn, Mrs. Rittenhouse, Mrs. Teasdale (all played by the same woman), without missing a diphthong:

As chairwoman of the reception committee, I welcome you with open arms.

Is that so? How late do you stay open?

I've sponsored your appointment because I feel you are the most able statesman in all Freedonia.

Well, that covers a lot of ground. Say, you cover a lot of ground yourself. You'd better beat it. I hear they're going to tear you down and put up an office building where you're standing. You can leave in a taxi. If you can't leave in a taxi, you can leave in a huff. If that's too soon, you can leave in a minute and a huff. You know you haven't stopped talking since I came here? You must have been vaccinated with a phonograph needle.

They recall his annihilations of high society ("The strains of Verdi will come back to you tonight, and Mrs. Claypool's check will come back to you in the morning"), the campus ("But Professor Wagstaff, if we tear down the dormitories where will the students sleep?" "Where they always slept. In the classroom"), the medical profession ("Either this man is dead or my watch has stopped"), statecraft ("We have to have a war. I've already paid a month's rent on the battlefield").

They quote anew the offscreen anecdotes, recalling, for example, how Groucho had approached Greta Garbo from behind, lifted her hat, and then apologized: "Sorry, I thought you were a guy I knew from Pittsburgh." How he rejected the offer of a Hollywood group: "I don't want to join any organization that would have me as a member." How he responded when the members of an anti-Semitic swimming club refused admission to his daughter: "She's only half Jewish. How about if she only goes in up to her waist?"

The youngest fans -- and there are many in attendance -- know another Groucho: the master of ceremonies of their favorite quiz show, You Bet Your Life, equipped with a real moustache, operating sans props or supporting cast, fluently putting down guests like the housewife who proudly declared that she had twenty-two children because she loved her husband (Groucho: "I love my cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while") or the heavily accented linguist who boasted that he could speak eleven languages (Groucho: "Which one are you speaking now?").

The performer's well-known grenades detonate onstage and off, as audience members remind each other of richer times:

Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.

One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I don't know.

I never forget a face, but in your case I'll make an exception.

Outside of a dog, a book is man's best friend. Inside of a dog, it's too dark to read.

Even now this frail figure, this embodiment of Yeats's image of old age as a coat upon a coat hanger, throws a long shadow. He was, after all, the centerpiece of Duck Soup. In that film Groucho plays the dictator of a mythic country, Freedonia, and his extravagant satire so threatened Benito Mussolini that the fascist leader barred it from Italy. Groucho was also the star of Horse Feathers. Winston Churchill was watching that movie when the top Nazi official, Rudolf Hess, parachuted onto the Duke of Hamilton's estate carrying a peace offer. If the Prime Minister would allow Germany to go to war against Russia unopposed, Germany would declare a ceasefire with Britain. To underline his point, that night twelve hundred Luftwaffe planes flew over London in the heaviest blitz of the two-year-old war. At the time Churchill was at Ditchley Park. His memoirs record that, after dinner, "News arrived of the heavy air raid. There was nothing that I could do about it so I watched the Marx Brothers in a comic film which my hosts had arranged. I went out twice to inquire about the air raid and heard it was bad. The merry film clicked on, and I was glad of the diversion."

It was Groucho whose jaunty attitude compelled the Missouri-born T. S. Eliot, the most prominent poet of the age, to write a fan letter meekly requesting an autographed portrait. The anti-Semitic bard and the Jewish comedian struck up an odd friendship, now recalled by the speaker on the Carnegie Hall stage: "I read up on Murder in the Cathedral and a few other things, and I thought I'd impress him. And all he wanted to talk about was the Marx Brothers. That's what happens when you come from St. Louis." This leads to a reminiscence of the poet's funeral, attended by most of the leading intellectuals of the time. Groucho could not erase the feeling that he was as out of place as a bagel at high tea. Laurence Olivier, seated nearby, calmed his fears and urged him to say a little something, if only for the widow's sake. "It was a tough audience for an old vaudeville actor. And this came to me while I was standing on the stage: It was a story about a man who was condemned to be hanged. And the priest said to him, 'Have you any last words to say before we spring the trap?' And the man says, 'Yes, I don't think this damn thing is safe.' "

Warmed by remembered laughter and current applause, Groucho seems for a moment to be his younger self as he reaches back for more anecdotes. He remembers the night he went to the Winter Garden when Harry Houdini headlined the show. "I was sans moustache. That means 'without.' I'm sitting in the second row and Houdini is doing a trick. He would take some needles and put them in his mouth. And then a spool of thread. And then he would thread the needles with his tongue. He asked for a volunteer out in the audience. And who do you think went up on the stage? And he opened his mouth wide: 'I want to prove that there's no trickery. What do you see in there?' And I said, 'Pyorrhea.' "

As he goes on, the energy and affection of the audience are reflected in his invigorated movements and sturdier voice. He nods to an accompanist, Marvin Hamlisch, and with surprising fervor summons up a song from the distant past -- a 1914 number disowned by his friend Irving Berlin, but which Groucho has always loved because it spoke out against war. In these last fading days of the Vietnam conflict, he wants everyone to know how he feels. (They already know; Groucho is on record as suggesting that the only way to get rid of President Nixon is assassination.) Taking the part of the devil addressing his son, Groucho croons Irving Berlin's forgotten tune:

You stay down here where you belong.

The folks above you, they don't know right from wrong.

To please their kings they've all gone out to war,

But not a one of them knows what they're fighting for.

Way up above they say that I'm a devil and I'm bad;

But the kings up there are bigger devils than your dad;

They're breaking the hearts of mothers,

Making butchers out of brothers;

You'll find more hell up there than there is down below!

The house booms its approval. Heartened, the speaker delightedly rambles on, scattering anecdotes like coins before the crowd. He recalls an old acquaintance, Otto Kahn, who walked down Fifth Avenue with a deformed friend. "You know," said Kahn, "I used to be a Jew." His friend responded, "Really? I used to be a hunchback." Groucho drops the name of his old friend W. C. Fields. "One day he allowed me in his house. And he had a ladder leading to an attic. And in this attic he had fifty thousand dollars' worth of whiskey. And I say to him, 'Bill, what have [you] got that booze there for? We haven't had prohibition in twenty-five years.' He says: 'It may come back.' "

And yet when Groucho takes his final curtain calls and the house lights are turned up, there remains a melancholy undertow to this unprecedented evening of laughter and memories. The star's complicated and irrepressible siblings have gone, Chico in 1961, Harpo three years later. Groucho will be next, and the general feeling is that the event is not far away. So the audience lingers in the aisles, reluctant to leave the theater, as if staying a bit longer might give the star a few more ergs of vitality, a few more months of life.

Most New Yorkers get from their apartments to the concert in about twenty minutes. It has taken Groucho more than six decades to get to Carnegie Hall. Tales of that trek have been related from the first days of his celebrity. They change with the venue, the journalist, and sometimes the mood of the teller. Yet the hard facts of his life and art are as unique, as beguiling -- and, in a funny way, as American -- as anything he has ever invented for public consumption.

From the Hardcover edition.

On the night of May 21, 1972, a frail, bald, eighty-two-year-old trouper enters from the wings of Carnegie Hall and takes center stage. He has not performed in New York for some fifty years, and in that time he has risen to the status of pantheon figure. He has been on the cover of Time twice. Scholars have written Ph.D. theses about his humor; his remarks have appeared in H. L. Mencken's The American Language, as well as in Bartlett's Familiar Quotations and The Oxford Dictionary of Quotations. Whatever awards broadcasting has to offer he has won. He has been impersonated by George Gershwin, made the subject of a Broadway musical, feted in London and Paris. The French government has just invited him to Cannes, where he is to be made Commandeur dans l'Ordre dès Arts et dès Lettres.

Ticket holders have become used to him as an ageless two-dimensional black-and-white figure. They have to get used to him as a man -- especially this man. For arthritis and small strokes have made his missteps a parody of the old choreography, and his rheumy eyes can barely decipher the cue cards. All the same, he seems to occupy the entire hall, and 2,800 onlookers, some of them sporting clawhammer coats, greasepaint moustaches, and oversize cigars in homage to the speaker's signature costume, rise to their feet and applaud for nearly five minutes. Groucho Marx is no longer in full control of his body or his memory, but his fans have decided that these infirmities are irrelevant and unworthy of comment. As he sings and reminisces in a broken voice, senior members of the audience look past old age to see the springy vaudevillian of their youth, playing straight man to his brother in a schoolroom routine:

What is the shape of the world?

I don't know.

Well, what shape are my cufflinks?

Square.

Not my weekday cufflinks. The ones I wear on Sundays.

Oh. Round.

All right, what is the shape of the world?

Square on weekdays, round on Sundays.

What are the principal parts of a cat?

Eyes, ears, neck, feet.

You forgot the most important. What does a cat have that you don't have?

Kittens.

Middle-aged fans are more familiar with his celebrated stage lines, supposedly launched when one of his brothers tried to throw him off stride:

The garbage man is outside!

Tell him we don't want any.

I'd like-a to say goom-bye to your wife.

Who wouldn't?

In their minds the past fuses with the present, and they recall the outrageous comedian of some forty years before capering in films, walking on half-bent knees and waggling his expressive eyebrows as he insults plutocrats, pursuing or insulting Mrs. Upjohn, Mrs. Rittenhouse, Mrs. Teasdale (all played by the same woman), without missing a diphthong:

As chairwoman of the reception committee, I welcome you with open arms.

Is that so? How late do you stay open?

I've sponsored your appointment because I feel you are the most able statesman in all Freedonia.

Well, that covers a lot of ground. Say, you cover a lot of ground yourself. You'd better beat it. I hear they're going to tear you down and put up an office building where you're standing. You can leave in a taxi. If you can't leave in a taxi, you can leave in a huff. If that's too soon, you can leave in a minute and a huff. You know you haven't stopped talking since I came here? You must have been vaccinated with a phonograph needle.

They recall his annihilations of high society ("The strains of Verdi will come back to you tonight, and Mrs. Claypool's check will come back to you in the morning"), the campus ("But Professor Wagstaff, if we tear down the dormitories where will the students sleep?" "Where they always slept. In the classroom"), the medical profession ("Either this man is dead or my watch has stopped"), statecraft ("We have to have a war. I've already paid a month's rent on the battlefield").

They quote anew the offscreen anecdotes, recalling, for example, how Groucho had approached Greta Garbo from behind, lifted her hat, and then apologized: "Sorry, I thought you were a guy I knew from Pittsburgh." How he rejected the offer of a Hollywood group: "I don't want to join any organization that would have me as a member." How he responded when the members of an anti-Semitic swimming club refused admission to his daughter: "She's only half Jewish. How about if she only goes in up to her waist?"

The youngest fans -- and there are many in attendance -- know another Groucho: the master of ceremonies of their favorite quiz show, You Bet Your Life, equipped with a real moustache, operating sans props or supporting cast, fluently putting down guests like the housewife who proudly declared that she had twenty-two children because she loved her husband (Groucho: "I love my cigar, but I take it out of my mouth once in a while") or the heavily accented linguist who boasted that he could speak eleven languages (Groucho: "Which one are you speaking now?").

The performer's well-known grenades detonate onstage and off, as audience members remind each other of richer times:

Time flies like an arrow. Fruit flies like a banana.

One morning I shot an elephant in my pajamas. How he got in my pajamas I don't know.

I never forget a face, but in your case I'll make an exception.

Outside of a dog, a book is man's best friend. Inside of a dog, it's too dark to read.

Even now this frail figure, this embodiment of Yeats's image of old age as a coat upon a coat hanger, throws a long shadow. He was, after all, the centerpiece of Duck Soup. In that film Groucho plays the dictator of a mythic country, Freedonia, and his extravagant satire so threatened Benito Mussolini that the fascist leader barred it from Italy. Groucho was also the star of Horse Feathers. Winston Churchill was watching that movie when the top Nazi official, Rudolf Hess, parachuted onto the Duke of Hamilton's estate carrying a peace offer. If the Prime Minister would allow Germany to go to war against Russia unopposed, Germany would declare a ceasefire with Britain. To underline his point, that night twelve hundred Luftwaffe planes flew over London in the heaviest blitz of the two-year-old war. At the time Churchill was at Ditchley Park. His memoirs record that, after dinner, "News arrived of the heavy air raid. There was nothing that I could do about it so I watched the Marx Brothers in a comic film which my hosts had arranged. I went out twice to inquire about the air raid and heard it was bad. The merry film clicked on, and I was glad of the diversion."

It was Groucho whose jaunty attitude compelled the Missouri-born T. S. Eliot, the most prominent poet of the age, to write a fan letter meekly requesting an autographed portrait. The anti-Semitic bard and the Jewish comedian struck up an odd friendship, now recalled by the speaker on the Carnegie Hall stage: "I read up on Murder in the Cathedral and a few other things, and I thought I'd impress him. And all he wanted to talk about was the Marx Brothers. That's what happens when you come from St. Louis." This leads to a reminiscence of the poet's funeral, attended by most of the leading intellectuals of the time. Groucho could not erase the feeling that he was as out of place as a bagel at high tea. Laurence Olivier, seated nearby, calmed his fears and urged him to say a little something, if only for the widow's sake. "It was a tough audience for an old vaudeville actor. And this came to me while I was standing on the stage: It was a story about a man who was condemned to be hanged. And the priest said to him, 'Have you any last words to say before we spring the trap?' And the man says, 'Yes, I don't think this damn thing is safe.' "

Warmed by remembered laughter and current applause, Groucho seems for a moment to be his younger self as he reaches back for more anecdotes. He remembers the night he went to the Winter Garden when Harry Houdini headlined the show. "I was sans moustache. That means 'without.' I'm sitting in the second row and Houdini is doing a trick. He would take some needles and put them in his mouth. And then a spool of thread. And then he would thread the needles with his tongue. He asked for a volunteer out in the audience. And who do you think went up on the stage? And he opened his mouth wide: 'I want to prove that there's no trickery. What do you see in there?' And I said, 'Pyorrhea.' "

As he goes on, the energy and affection of the audience are reflected in his invigorated movements and sturdier voice. He nods to an accompanist, Marvin Hamlisch, and with surprising fervor summons up a song from the distant past -- a 1914 number disowned by his friend Irving Berlin, but which Groucho has always loved because it spoke out against war. In these last fading days of the Vietnam conflict, he wants everyone to know how he feels. (They already know; Groucho is on record as suggesting that the only way to get rid of President Nixon is assassination.) Taking the part of the devil addressing his son, Groucho croons Irving Berlin's forgotten tune:

You stay down here where you belong.

The folks above you, they don't know right from wrong.

To please their kings they've all gone out to war,

But not a one of them knows what they're fighting for.

Way up above they say that I'm a devil and I'm bad;

But the kings up there are bigger devils than your dad;

They're breaking the hearts of mothers,

Making butchers out of brothers;

You'll find more hell up there than there is down below!

The house booms its approval. Heartened, the speaker delightedly rambles on, scattering anecdotes like coins before the crowd. He recalls an old acquaintance, Otto Kahn, who walked down Fifth Avenue with a deformed friend. "You know," said Kahn, "I used to be a Jew." His friend responded, "Really? I used to be a hunchback." Groucho drops the name of his old friend W. C. Fields. "One day he allowed me in his house. And he had a ladder leading to an attic. And in this attic he had fifty thousand dollars' worth of whiskey. And I say to him, 'Bill, what have [you] got that booze there for? We haven't had prohibition in twenty-five years.' He says: 'It may come back.' "

And yet when Groucho takes his final curtain calls and the house lights are turned up, there remains a melancholy undertow to this unprecedented evening of laughter and memories. The star's complicated and irrepressible siblings have gone, Chico in 1961, Harpo three years later. Groucho will be next, and the general feeling is that the event is not far away. So the audience lingers in the aisles, reluctant to leave the theater, as if staying a bit longer might give the star a few more ergs of vitality, a few more months of life.

Most New Yorkers get from their apartments to the concert in about twenty minutes. It has taken Groucho more than six decades to get to Carnegie Hall. Tales of that trek have been related from the first days of his celebrity. They change with the venue, the journalist, and sometimes the mood of the teller. Yet the hard facts of his life and art are as unique, as beguiling -- and, in a funny way, as American -- as anything he has ever invented for public consumption.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Thoroughly absorbing.... Groucho has finally gotten a biographer worthy of him.”–The Wall Street Journal

Descriere

The author of "The Last Empire" takes an authoritative, affectionate, and unsparingly honest look at the life and times of Groucho, the comedian behind the ever-present cigar. of photos.