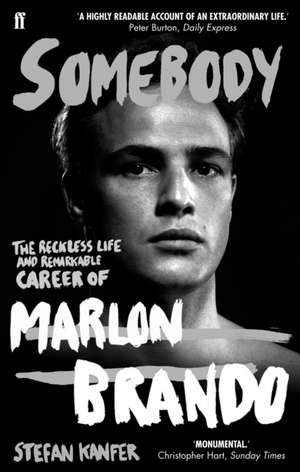

Somebody

Autor Stefan Kanferen Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 iul 2011

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 82.87 lei 3-5 săpt. | +12.85 lei 6-12 zile |

| FABER & FABER – 6 iul 2011 | 82.87 lei 3-5 săpt. | +12.85 lei 6-12 zile |

| Vintage Books USA – 31 oct 2009 | 111.99 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 82.87 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 124

Preț estimativ în valută:

15.86€ • 16.59$ • 13.17£

15.86€ • 16.59$ • 13.17£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 13-27 martie

Livrare express 26 februarie-04 martie pentru 22.84 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780571244133

ISBN-10: 0571244130

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 123 x 198 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

ISBN-10: 0571244130

Pagini: 384

Dimensiuni: 123 x 198 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Ediția:Main

Editura: FABER & FABER

Notă biografică

Stefan Kanfer’s books include The Eighth Sin, A Summer World, The Last Empire, Serious Business, Groucho, Ball of Fire, and Stardust Lost. He was a writer and editor at Time for more than twenty years and was its first bylined film critic, a post he held between 1967 and 1972. He is also the primary interviewer in the Academy Award-nominated documentary The Line King and editor of an anthology of Groucho Marx’s comedy, The Essential Groucho. He is a Literary Lion of the New York Public Library and the recipient of numerous writing awards. He lives in New York City and on Cape Cod.

Extras

1

1924-1942

In Disgrace with Fortune

It was typical of Marlon to enter the world upside down. The breech birth took place shortly after 11 p.m., April 3, 1924, in the Omaha Maternity Hospital.

His earliest home was right out of the imaginings of Hollywood at a time when the film industry, dominated by Jewish immigrants, was beginning to reinvent its host country. If status was denied to these rough, uneducated Eastern Europeans, observed historian Neal Gabler, the movies offered an ingenious option. The first moguls "would fabricate their empire in the image of America. They would create its values and myths, its traditions and archetypes. It would be an America where fathers were strong, families stable, people attractive, resilient, resourceful, and decent." This is the superficially idyllic America into which Marlon was born.

Yet even in the peaceful Midwest, ideal turf of the Dream Factory, there were dark spots no one could ignore. In the year of Marlon's birth, for example, two adolescents, Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold, kidnapped and murdered fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks in a Chicago suburb. That was in May. Detectives closed in shortly afterward, the culprits were arraigned in June, and by August they were on trial for their lives. The defense, headed by star lawyer Clarence Darrow, enlisted mind doctors, "alienists," in the parlance of the day, to establish irresponsibility by reason of insanity. Sigmund Freud was asked to aid the cause, but he was in fragile health and declined the invitation. After being called "cowardly perverts," "atheists," and "mad dogs," Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life imprisonment. But the debate about capital punishment continued unchecked, touching the plains and cities of Nebraska. At virtually the same time, Chicago crime raged on, fueled by Prohibition. The outlawing of alcohol had become official in 1920; since then the racketeers and illegal importers had grown, peddling booze to the country's flourishing speakeasies. Turf wars began: Al Capone's brother Frank was gunned down by police when he led some two hundred armed men into Cicero, Illinois, in support of ?Mafia-?backed politicians. And North Side gang leader Dion O'Banion was shot and killed by three men who had entered his flower shop after hours. The murder began a ?five-?year war with the Capone gang that was to culminate in the notorious St. Valentine's Day massacre.

Closer to home, Omaha wrestled with its own Prohibition troubles and with a more intractable problem. Since the end of the Great War, the city's African American population had more than doubled. With the influx came resentments and racial taunts. The Omaha Bee was particularly inflammatory. The paper's favorite topic concerned rumored assaults and rapes of white women by black men. The accused were hauled before judges and juries. When they failed to convict, another newspaper, the Mediator, warned of vigilantism in Omaha if the "respectable colored population could not purge those from the Negro community who were assaulting white girls." A few months later a volatile combination of labor unrest and racial suspicion erupted. Before it ended, a black man was lynched, two other blacks died of wounds suffered during a street fight, the county courthouse lay in ruins, and the city came under federal military control.

All these provoked conversation at the Brando dinner table through the 1920s and early 1930s, marking an odd contrast to the rustic atmosphere at 1026 South Street. Outwardly all was lyrical. Three children--two pretty sisters and their robust younger brother--played in the large front yard; the backdrop was a capacious wood-shingled house redolent of fresh-cut hay, wild flowers, and smoke from a wood-burning stove. In the next decade Andy Hardy movies would take place in just such an environment.

But there was a secondary aroma, and it revealed what no passerby could sense. "When my mother drank," recalled Marlon, "her breath had a sweetness to it I lack the vocabulary to describe." A furtive alcoholic, she took frequent hits from a bottle she called her "change-of-life" medicine. Dodie-Dorothy Pennebaker Brando-began to spend longer and longer periods with that vessel until, Marlon noted in his memoir, "the anguish that her drinking produced was that she preferred getting drunk to caring for us."

"Us" referred to Marlon senior and his children, Frances (known to the family as Frannie), Jocelyn (Tiddy), and Marlon junior (Bud). Dodie had reasons for allowing her husband to fend for himself. Wrote his namesake, "It was an era when a traveling salesman slipped five dollars to a bellboy, who would return with a pint of whisky and a hooker. My pop was such a man."

The condition of such families as the Brandos, and such cities as Omaha, was well known to Sinclair Lewis. He had portrayed them in his 1922 bestseller Babbitt, with its hypocritical real-estate-salesman protagonist and his unhappy wife, and the superficially respectable city in which they lived. "At that moment in Zenith, a cocaine-runner and a prostitute were drinking cocktails in Healy Hanson's saloon on Front Street. Since national prohibition was now in force, and since Zenith was notoriously law-abiding, they were compelled to keep the cocktails innocent by drinking them out of tea-cups. The lady threw her cup at the cocaine-runner's head. He worked his revolver out of the pocket in his sleeve, and casually murdered her."

For Marlon senior, as for George F. Babbitt, money was not a problem; a peddler of products for contractors and architects, the paterfamilias earned more than enough to maintain his family in solid middle-class comfort. Affection, however, was in short supply. He would return home to shower Dodie with gifts, then journey back to a life of one-night stands. There were presents for the kids as well, but precious little concern. Marlon senior continually denigrated his namesake; he mocked the boy's behavior, his way of speaking, his posture. Hugs were only dispensed on birthdays or at Christmastime; Junior couldn't recall a single compliment from his father from kindergarten through adolescence. As a result the child sought attention elsewhere-mainly at school, where he made a habit of flouting authority, and getting punished for it.

Senior's ominous moods and black silences were harder for his daughters to deal with. "I don't remember forgiveness," Frannie Brando wrote many years later. "No forgiveness! In our home, there was blame, shame, and punishment that very often had no relationship to the 'crime,' and I think the sense of burning injustice it left with all of us marked us deeply."

That behavior had profound and twisted sources. Although a number of biographies have suggested that the name Brando was originally spelled Brandeau and was of French origin, the family's founding relative was Johann Wilhelm Brandau, a German immigrant who settled in New York State in the early 1700s. Neighbors who remembered Marlon senior from his school days said there was something "Teutonic and closed" about the youth, but this may have been the perception of hindsight. In any case, he had reason to be withdrawn; his mother ran off without a backward glance when the boy was four. Thereafter, the abandoned father varied between dark and uncommunicative periods and loud, unpredictable demands. In adolescence, Marlon senior was shunted from one spinster aunt to another. He grew up rude and misogynistic, given to binge drinking and bullying. Bud came to see his father in cinematic terms as a British officer in the Bengal Lancers, "perhaps a Victor McLaglen with more refinement."

Dorothy Pennebaker came from a background of mavericks, gold prospectors, and Christian Scientists. She married at twenty-one but continued to attract whistles and social attention as a vivacious flapper with artistic yearnings. Early on, Dodie made a small name for herself by cultivating members of Omaha's little bohemian colony, and beating out the competition for roles at the Omaha Community Playhouse. From walk-ons and juvenile leads she progressed to starring parts in Pygmalion and Anna Christie. It occurred to Dodie that she might take a trip to New York and try a stab at Broadway-especially after she won rave reviews for her appearance in Beyond the Horizon opposite a twenty-one-year-old Omahan named Henry Fonda. All too soon, though, Marlon senior's rages, as well as his open and continual adulteries, eroded her confidence on- and offstage. She consumed more liquor, took her own lovers, and narrowed her creative impulses.

Like many homes of the period, the Brando house had a piano in the parlor. Radio was still in its infancy, and recordings were still only a pale echo of true musical sound. Dodie had received lessons as a child, and she still got more pleasure out of playing than she did out of listening. Solos at the keyboard supplanted group work at the theater. Surrounded by her children--in one of the very few family activities-she played folk airs and popular numbers, from Irving Berlin's inventive tunes to a list of lesser numbers, including "I'm Looking Over a Four-Leaf Clover" and "Am I Blue?" To please her, Marlon learned them all. He could never summon up the digits of his Social Security I.D., and there were times when he couldn't recall his own telephone number. But the music and lyrics from those days around the keyboard never left him. When, at the age of sixty-five, he wrote his autobiography, scores of titles were suggested by friends and publishers, but in the end he settled on Songs My Mother Taught Me.

2

When Bud was six, the Calcium Carbonate Corporation offered his father a new job as sales manager. Employment opportunities were few in 1930, the first full year of the Depression. Marlon senior seized the day, even though it meant relocation to Evanston, Illinois. His wife was not so happy with the decision; she still clung to the fading illusion of herself as a stage star, and Evanston had no playhouse and few nonconformists.

Dodie struggled to get her bearings in the new neighborhood. Melancholia settled in like an old acquaintance who had come for a weekend visit and refused to go away. Every day the Chicago Tribune brought bad news, and every week Time magazine summed them up. Breadlines across the country, new bankruptcies. And lynchings; God, those poor people. She sometimes read the stories aloud to the kids, unsure of whether the reports went over their heads or burrowed into their psyches. "All night two hundred men and boys searched for Davie Harris, found him at dawn, cringing in an empty barn. They lugged him up to the levee, mocked his yammerings for mercy. 'De Lord save me,' cried Harris as guns cracked about him, shots riddled his body. Deputy Sheriff Dayu arrived 'too late' to make arrests. Deputy Sheriff Courtney expected no investigation 'until next fall.' "

In the back of the publications Dodie read news of live performances in the East. They opened old wounds. Like the rest of the country, Broadway was suffering from financial woes. The year before there had been 233 productions; this year there would be 187, and fewer were scheduled for next year. Vaudeville was reeling; five years before there were fifteen hundred theaters in the circuits. One fifth remained. And yet the Fabulous Invalid went on, as it always did, as it always would. Eva Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory staged Allison's House, based on the life of Emily Dickinson; it was said to be a shoo-in for the Pulitzer. Maxwell Anderson's Elizabeth the Queen starred Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne at the Guild Theatre. Eugene O'Neill's Marco Millions was successfully revived at the Liberty. The Gershwins had a new show, Girl Crazy. "I Got Rhythm" was on the radio every night; you couldn't get away from it. The columnists said that Ethel Merman could hold a note longer than the Chase National Bank. And Harold Arlen had written the score for Earl Carroll's Vanities. I should have gone east, Dodie would muse aloud. It's not too late even now.

Then again, that might not be the best move. Three quarters of the New York actors were supposed to be heading for Hollywood. And why not? The studios dominated show business now that sound had come in. Powerful men ran them: Goldwyn, Mayer, the Warners, Zanuck. These dream merchants could read the public like a map. All Quiet on the Western Front and Hell's Angels were playing everywhere. Who knew that this would be the year to look back at the Great War? They did. Who knew that you could make money with a gangster picture like The Widow from Chicago? Who knew you could make a star of Edward G. Robinson, a little Jewish man with fat lips? They did. Maybe I should have gone west, not middle west, Dodie grumbled. Meantime, the neighbors whispered that Mrs. Brando was the kind of woman who saw the glass as half full. That was because she had drunk the other half.

The rumors were cruel, and they were accurate. Too many afternoons Dodie disappeared into an alcohol-saturated haze, unreachable by her children. Frannie and Tiddy were on the cusp of adolescence and found new friends at the tony Lincoln School. Bud attended the same institution, but retreated into his own fantasies. The most obsessive of these concerned the family housekeeper, a young woman of Danish and Indonesian descent called Ermi. During the day he played card games with her; at night the two often slept in the same bed. She was nude, he remembered-though this might have been a boy's wishful dream- and a sound sleeper. On his part the attachment was all-consuming; to her it was of no importance whatever. In fact, she never bothered to tell him that she was about to be married. The housekeeper merely informed him one day that she was leaving on a trip and would return soon.

It took several weeks for Bud to realize that Ermi was not coming back. The night he realized she was gone forever, he experienced a foretaste of death. "I felt abandoned," he said almost five decades later. "My mother had long ago deserted me for her bottle; now Ermi was gone, too." To Bud this was one of the informing incidents of his childhood. Looking back he decided that Ermi's defection kept repeating itself in his life. He would seek out a woman who would encourage him up to a point-and then abruptly and permanently exit. According to Marlon, the day Ermi went away "I became estranged from this world." That summary contained everything a self-dramatizing figure could desire: bittersweet melodrama, unrequited romance, and Freudian insight. It might even have been true.

In her study Adult Children of Alcoholics, Dr. Janet Geringer Woi? titz lists the characteristics of her subjects when young. They tend to:

Guess what normal behavior is.

Lie when it would be just as easy to tell the truth.

Judge themselves without mercy.

Constantly seek approval and affirmation.

Be impulsive. Such behavior would lead to confusion, self-loathing and loss of control.

All these attributes were part of Bud's emerging temperament. At home, as he saw it, "there was a constant, grinding, unseen miasma of anger." Infected by the rage around him, he continued to act out his hostilities, burning insects, slashing tires, tiptoeing close to birds-and then plugging them with the BB gun his father had given him as a birthday present. Bud was no happier in the classroom than he was in the house. One morning he took a can of lighter fluid, squirted the word shit on a blackboard and ignited the letters. The incident helped to burnish his bad-boy reputation; he seemed to thrive on that. All the same, after every incident there came a time of remorse and self-reproach.

From the Hardcover edition.

1924-1942

In Disgrace with Fortune

It was typical of Marlon to enter the world upside down. The breech birth took place shortly after 11 p.m., April 3, 1924, in the Omaha Maternity Hospital.

His earliest home was right out of the imaginings of Hollywood at a time when the film industry, dominated by Jewish immigrants, was beginning to reinvent its host country. If status was denied to these rough, uneducated Eastern Europeans, observed historian Neal Gabler, the movies offered an ingenious option. The first moguls "would fabricate their empire in the image of America. They would create its values and myths, its traditions and archetypes. It would be an America where fathers were strong, families stable, people attractive, resilient, resourceful, and decent." This is the superficially idyllic America into which Marlon was born.

Yet even in the peaceful Midwest, ideal turf of the Dream Factory, there were dark spots no one could ignore. In the year of Marlon's birth, for example, two adolescents, Richard Loeb and Nathan Leopold, kidnapped and murdered fourteen-year-old Bobby Franks in a Chicago suburb. That was in May. Detectives closed in shortly afterward, the culprits were arraigned in June, and by August they were on trial for their lives. The defense, headed by star lawyer Clarence Darrow, enlisted mind doctors, "alienists," in the parlance of the day, to establish irresponsibility by reason of insanity. Sigmund Freud was asked to aid the cause, but he was in fragile health and declined the invitation. After being called "cowardly perverts," "atheists," and "mad dogs," Leopold and Loeb were sentenced to life imprisonment. But the debate about capital punishment continued unchecked, touching the plains and cities of Nebraska. At virtually the same time, Chicago crime raged on, fueled by Prohibition. The outlawing of alcohol had become official in 1920; since then the racketeers and illegal importers had grown, peddling booze to the country's flourishing speakeasies. Turf wars began: Al Capone's brother Frank was gunned down by police when he led some two hundred armed men into Cicero, Illinois, in support of ?Mafia-?backed politicians. And North Side gang leader Dion O'Banion was shot and killed by three men who had entered his flower shop after hours. The murder began a ?five-?year war with the Capone gang that was to culminate in the notorious St. Valentine's Day massacre.

Closer to home, Omaha wrestled with its own Prohibition troubles and with a more intractable problem. Since the end of the Great War, the city's African American population had more than doubled. With the influx came resentments and racial taunts. The Omaha Bee was particularly inflammatory. The paper's favorite topic concerned rumored assaults and rapes of white women by black men. The accused were hauled before judges and juries. When they failed to convict, another newspaper, the Mediator, warned of vigilantism in Omaha if the "respectable colored population could not purge those from the Negro community who were assaulting white girls." A few months later a volatile combination of labor unrest and racial suspicion erupted. Before it ended, a black man was lynched, two other blacks died of wounds suffered during a street fight, the county courthouse lay in ruins, and the city came under federal military control.

All these provoked conversation at the Brando dinner table through the 1920s and early 1930s, marking an odd contrast to the rustic atmosphere at 1026 South Street. Outwardly all was lyrical. Three children--two pretty sisters and their robust younger brother--played in the large front yard; the backdrop was a capacious wood-shingled house redolent of fresh-cut hay, wild flowers, and smoke from a wood-burning stove. In the next decade Andy Hardy movies would take place in just such an environment.

But there was a secondary aroma, and it revealed what no passerby could sense. "When my mother drank," recalled Marlon, "her breath had a sweetness to it I lack the vocabulary to describe." A furtive alcoholic, she took frequent hits from a bottle she called her "change-of-life" medicine. Dodie-Dorothy Pennebaker Brando-began to spend longer and longer periods with that vessel until, Marlon noted in his memoir, "the anguish that her drinking produced was that she preferred getting drunk to caring for us."

"Us" referred to Marlon senior and his children, Frances (known to the family as Frannie), Jocelyn (Tiddy), and Marlon junior (Bud). Dodie had reasons for allowing her husband to fend for himself. Wrote his namesake, "It was an era when a traveling salesman slipped five dollars to a bellboy, who would return with a pint of whisky and a hooker. My pop was such a man."

The condition of such families as the Brandos, and such cities as Omaha, was well known to Sinclair Lewis. He had portrayed them in his 1922 bestseller Babbitt, with its hypocritical real-estate-salesman protagonist and his unhappy wife, and the superficially respectable city in which they lived. "At that moment in Zenith, a cocaine-runner and a prostitute were drinking cocktails in Healy Hanson's saloon on Front Street. Since national prohibition was now in force, and since Zenith was notoriously law-abiding, they were compelled to keep the cocktails innocent by drinking them out of tea-cups. The lady threw her cup at the cocaine-runner's head. He worked his revolver out of the pocket in his sleeve, and casually murdered her."

For Marlon senior, as for George F. Babbitt, money was not a problem; a peddler of products for contractors and architects, the paterfamilias earned more than enough to maintain his family in solid middle-class comfort. Affection, however, was in short supply. He would return home to shower Dodie with gifts, then journey back to a life of one-night stands. There were presents for the kids as well, but precious little concern. Marlon senior continually denigrated his namesake; he mocked the boy's behavior, his way of speaking, his posture. Hugs were only dispensed on birthdays or at Christmastime; Junior couldn't recall a single compliment from his father from kindergarten through adolescence. As a result the child sought attention elsewhere-mainly at school, where he made a habit of flouting authority, and getting punished for it.

Senior's ominous moods and black silences were harder for his daughters to deal with. "I don't remember forgiveness," Frannie Brando wrote many years later. "No forgiveness! In our home, there was blame, shame, and punishment that very often had no relationship to the 'crime,' and I think the sense of burning injustice it left with all of us marked us deeply."

That behavior had profound and twisted sources. Although a number of biographies have suggested that the name Brando was originally spelled Brandeau and was of French origin, the family's founding relative was Johann Wilhelm Brandau, a German immigrant who settled in New York State in the early 1700s. Neighbors who remembered Marlon senior from his school days said there was something "Teutonic and closed" about the youth, but this may have been the perception of hindsight. In any case, he had reason to be withdrawn; his mother ran off without a backward glance when the boy was four. Thereafter, the abandoned father varied between dark and uncommunicative periods and loud, unpredictable demands. In adolescence, Marlon senior was shunted from one spinster aunt to another. He grew up rude and misogynistic, given to binge drinking and bullying. Bud came to see his father in cinematic terms as a British officer in the Bengal Lancers, "perhaps a Victor McLaglen with more refinement."

Dorothy Pennebaker came from a background of mavericks, gold prospectors, and Christian Scientists. She married at twenty-one but continued to attract whistles and social attention as a vivacious flapper with artistic yearnings. Early on, Dodie made a small name for herself by cultivating members of Omaha's little bohemian colony, and beating out the competition for roles at the Omaha Community Playhouse. From walk-ons and juvenile leads she progressed to starring parts in Pygmalion and Anna Christie. It occurred to Dodie that she might take a trip to New York and try a stab at Broadway-especially after she won rave reviews for her appearance in Beyond the Horizon opposite a twenty-one-year-old Omahan named Henry Fonda. All too soon, though, Marlon senior's rages, as well as his open and continual adulteries, eroded her confidence on- and offstage. She consumed more liquor, took her own lovers, and narrowed her creative impulses.

Like many homes of the period, the Brando house had a piano in the parlor. Radio was still in its infancy, and recordings were still only a pale echo of true musical sound. Dodie had received lessons as a child, and she still got more pleasure out of playing than she did out of listening. Solos at the keyboard supplanted group work at the theater. Surrounded by her children--in one of the very few family activities-she played folk airs and popular numbers, from Irving Berlin's inventive tunes to a list of lesser numbers, including "I'm Looking Over a Four-Leaf Clover" and "Am I Blue?" To please her, Marlon learned them all. He could never summon up the digits of his Social Security I.D., and there were times when he couldn't recall his own telephone number. But the music and lyrics from those days around the keyboard never left him. When, at the age of sixty-five, he wrote his autobiography, scores of titles were suggested by friends and publishers, but in the end he settled on Songs My Mother Taught Me.

2

When Bud was six, the Calcium Carbonate Corporation offered his father a new job as sales manager. Employment opportunities were few in 1930, the first full year of the Depression. Marlon senior seized the day, even though it meant relocation to Evanston, Illinois. His wife was not so happy with the decision; she still clung to the fading illusion of herself as a stage star, and Evanston had no playhouse and few nonconformists.

Dodie struggled to get her bearings in the new neighborhood. Melancholia settled in like an old acquaintance who had come for a weekend visit and refused to go away. Every day the Chicago Tribune brought bad news, and every week Time magazine summed them up. Breadlines across the country, new bankruptcies. And lynchings; God, those poor people. She sometimes read the stories aloud to the kids, unsure of whether the reports went over their heads or burrowed into their psyches. "All night two hundred men and boys searched for Davie Harris, found him at dawn, cringing in an empty barn. They lugged him up to the levee, mocked his yammerings for mercy. 'De Lord save me,' cried Harris as guns cracked about him, shots riddled his body. Deputy Sheriff Dayu arrived 'too late' to make arrests. Deputy Sheriff Courtney expected no investigation 'until next fall.' "

In the back of the publications Dodie read news of live performances in the East. They opened old wounds. Like the rest of the country, Broadway was suffering from financial woes. The year before there had been 233 productions; this year there would be 187, and fewer were scheduled for next year. Vaudeville was reeling; five years before there were fifteen hundred theaters in the circuits. One fifth remained. And yet the Fabulous Invalid went on, as it always did, as it always would. Eva Le Gallienne's Civic Repertory staged Allison's House, based on the life of Emily Dickinson; it was said to be a shoo-in for the Pulitzer. Maxwell Anderson's Elizabeth the Queen starred Alfred Lunt and Lynn Fontanne at the Guild Theatre. Eugene O'Neill's Marco Millions was successfully revived at the Liberty. The Gershwins had a new show, Girl Crazy. "I Got Rhythm" was on the radio every night; you couldn't get away from it. The columnists said that Ethel Merman could hold a note longer than the Chase National Bank. And Harold Arlen had written the score for Earl Carroll's Vanities. I should have gone east, Dodie would muse aloud. It's not too late even now.

Then again, that might not be the best move. Three quarters of the New York actors were supposed to be heading for Hollywood. And why not? The studios dominated show business now that sound had come in. Powerful men ran them: Goldwyn, Mayer, the Warners, Zanuck. These dream merchants could read the public like a map. All Quiet on the Western Front and Hell's Angels were playing everywhere. Who knew that this would be the year to look back at the Great War? They did. Who knew that you could make money with a gangster picture like The Widow from Chicago? Who knew you could make a star of Edward G. Robinson, a little Jewish man with fat lips? They did. Maybe I should have gone west, not middle west, Dodie grumbled. Meantime, the neighbors whispered that Mrs. Brando was the kind of woman who saw the glass as half full. That was because she had drunk the other half.

The rumors were cruel, and they were accurate. Too many afternoons Dodie disappeared into an alcohol-saturated haze, unreachable by her children. Frannie and Tiddy were on the cusp of adolescence and found new friends at the tony Lincoln School. Bud attended the same institution, but retreated into his own fantasies. The most obsessive of these concerned the family housekeeper, a young woman of Danish and Indonesian descent called Ermi. During the day he played card games with her; at night the two often slept in the same bed. She was nude, he remembered-though this might have been a boy's wishful dream- and a sound sleeper. On his part the attachment was all-consuming; to her it was of no importance whatever. In fact, she never bothered to tell him that she was about to be married. The housekeeper merely informed him one day that she was leaving on a trip and would return soon.

It took several weeks for Bud to realize that Ermi was not coming back. The night he realized she was gone forever, he experienced a foretaste of death. "I felt abandoned," he said almost five decades later. "My mother had long ago deserted me for her bottle; now Ermi was gone, too." To Bud this was one of the informing incidents of his childhood. Looking back he decided that Ermi's defection kept repeating itself in his life. He would seek out a woman who would encourage him up to a point-and then abruptly and permanently exit. According to Marlon, the day Ermi went away "I became estranged from this world." That summary contained everything a self-dramatizing figure could desire: bittersweet melodrama, unrequited romance, and Freudian insight. It might even have been true.

In her study Adult Children of Alcoholics, Dr. Janet Geringer Woi? titz lists the characteristics of her subjects when young. They tend to:

Guess what normal behavior is.

Lie when it would be just as easy to tell the truth.

Judge themselves without mercy.

Constantly seek approval and affirmation.

Be impulsive. Such behavior would lead to confusion, self-loathing and loss of control.

All these attributes were part of Bud's emerging temperament. At home, as he saw it, "there was a constant, grinding, unseen miasma of anger." Infected by the rage around him, he continued to act out his hostilities, burning insects, slashing tires, tiptoeing close to birds-and then plugging them with the BB gun his father had given him as a birthday present. Bud was no happier in the classroom than he was in the house. One morning he took a can of lighter fluid, squirted the word shit on a blackboard and ignited the letters. The incident helped to burnish his bad-boy reputation; he seemed to thrive on that. All the same, after every incident there came a time of remorse and self-reproach.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Well-researched and beautifully written, the book is as fascinating . . . as the subject himself.” —Los Angeles Times

“Miraculous. . . . A landmark in Brando studies.” —David Thomson

“[A] vivid chronicle. . . . The Marlon Brando story is a fascinating and tragic one, and Kanfer gives it the size and understanding necessary to provide an enthralling read.” —Peter Bogdanovich

“Stefan Kanfer strikes an original note by portraying him, albeit with great sensitivity and tact, as a man permanently teetering on the brink of madness–clearly part of his mesmeric screen presence.” —The Sunday Times (London)

“Miraculous. . . . A landmark in Brando studies.” —David Thomson

“[A] vivid chronicle. . . . The Marlon Brando story is a fascinating and tragic one, and Kanfer gives it the size and understanding necessary to provide an enthralling read.” —Peter Bogdanovich

“Stefan Kanfer strikes an original note by portraying him, albeit with great sensitivity and tact, as a man permanently teetering on the brink of madness–clearly part of his mesmeric screen presence.” —The Sunday Times (London)