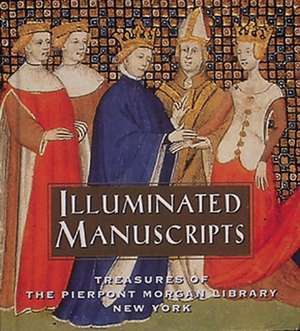

Illuminated Manuscripts: Treasures of the Pierpont Morgan Library New York: Tiny Folio

Pierpont Morgan Library Autor William M. Voelkle, Susan L'Engleen Limba Engleză Hardback – 30 sep 1998

Glorious works of art as well as documents of bygone eras, painted an illuminated manuscripts supply perhaps the greatest and by far the best-preserved evidence of daily life during the Middle Ages and Renaissance. This Tiny Folio draws on one of the greatest collections in the world to illustrate the angels, demons, and everyday denizens of the medieval world.

Din seria Tiny Folio

-

Preț: 74.82 lei

Preț: 74.82 lei - 11%

Preț: 379.29 lei

Preț: 379.29 lei -

Preț: 68.68 lei

Preț: 68.68 lei -

Preț: 68.93 lei

Preț: 68.93 lei -

Preț: 75.01 lei

Preț: 75.01 lei -

Preț: 75.88 lei

Preț: 75.88 lei -

Preț: 75.64 lei

Preț: 75.64 lei -

Preț: 68.93 lei

Preț: 68.93 lei -

Preț: 68.99 lei

Preț: 68.99 lei -

Preț: 68.73 lei

Preț: 68.73 lei -

Preț: 77.11 lei

Preț: 77.11 lei -

Preț: 68.78 lei

Preț: 68.78 lei -

Preț: 62.83 lei

Preț: 62.83 lei -

Preț: 66.78 lei

Preț: 66.78 lei -

Preț: 69.05 lei

Preț: 69.05 lei - 19%

Preț: 28.20 lei

Preț: 28.20 lei -

Preț: 59.55 lei

Preț: 59.55 lei -

Preț: 68.46 lei

Preț: 68.46 lei - 20%

Preț: 55.20 lei

Preț: 55.20 lei - 24%

Preț: 50.75 lei

Preț: 50.75 lei - 21%

Preț: 53.59 lei

Preț: 53.59 lei - 20%

Preț: 55.20 lei

Preț: 55.20 lei - 6%

Preț: 65.00 lei

Preț: 65.00 lei -

Preț: 68.84 lei

Preț: 68.84 lei

Preț: 61.76 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 93

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.82€ • 12.29$ • 9.76£

11.82€ • 12.29$ • 9.76£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 24 martie-07 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 20.07 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789202161

ISBN-10: 0789202166

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 107 x 114 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Tiny Folio

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0789202166

Pagini: 288

Dimensiuni: 107 x 114 x 22 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Tiny Folio

Locul publicării:United States

Cuprins

Foreword

Introduction

Biblical Scenes

Saints, Rites, and Rituals

Royalty, Pastimes, and Professions

Flora and Fauna

The Supernatural

Selected Bibliography

Index of Illustrations

Introduction

Biblical Scenes

Saints, Rites, and Rituals

Royalty, Pastimes, and Professions

Flora and Fauna

The Supernatural

Selected Bibliography

Index of Illustrations

Notă biografică

Charles E. Pierce, Jr., is former director of the Pierpont Morgan Library.

William M. Voelkle is the Library's Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts.

Susan Lengle is a curatorial assistant.

William M. Voelkle is the Library's Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts.

Susan Lengle is a curatorial assistant.

Extras

Foreword

It is generally acknowledged that Pierpont Morgan was the greatest collector of our century. Within a period of some twenty years before his death in 1913, he assembled vast collections of antiquities, paintings, sculptures, tapestries, porcelains, watches, and other decorative objects. But none of these was to find a permanent home in The Pierpont Morgan Library. That building, commissioned from Charles McKim in 1902 and finished in 1906, was destined to house the collections that were evidently closest to his heart: autograph manuscripts, rare books and bindings, old master drawings, Mesopotamian cylinder seals, papyri, and medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. Of these, it is perhaps the last for which the Library is best known.

Pierponts son, Jack, who founded the Morgan Library in 1924, made important additions until his death in 1943. The present volume, which includes many manuscripts acquired since 1943, conveys the full range and quality of the collection as it now exists. By making accessible to a larger audience the delights of an art form usually buried in closed books, this volume also helps fulfill the goals of the founders.

Charles E. Pierce, Jr.

Director, The Pierpont Morgan Library

Introduction

Medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts are many-splendored things, objects of both great beauty and tremendous pictorial variety and richness. They are like museums between the covers of books and constitute the largest surviving body of painting from this period. Because the pictures have been protected by bindings, their incredible freshness has been preserved and they have avoided the vicissitudes suffered by panel and wall painting. Since the miniatures have been largely spared from the hand of the restorer, they provide the most reliable resource for the study of medieval and Renaissance color. But since they are parts of books much can also be learned about how earlier men and women lived, what they wrote, read, and thought, and how they used and contributed to knowledge. One can also observe the different ways in which books were written, decorated, and bound over the centuries. The specific subjects selected, the nature of their representations, and the size of their illustrations are also telling.

The types of books, too, speak much about the medieval citizens personal concerns. Aside from Bibles, there are all kinds of service books, such as Sacramentaries, Missals, Lectionaries, Graduals, Breviaries, Antiphonaries, Psalters, and Books of Hours; various theological works and commentaries; and lives of the saints and other forms of devotional literature. There are scientific manuscripts dealing with astrology, astronomy, medicine, plants, animals, and minerals; and works of a more practical nature telling when and how to plant, how to take care of horses and dogs, how to hunt and fight. There are works of historical interest, such as biographies and chronicles, and texts dealing with law, exploration, and cartography. And there are books for edification, such as works by classical authors, and works for pleasure, such as the medieval romances. The images in such manuscripts are incredibly varied, however, and have remained largely hidden and little known. Furthermore, they are also light sensitive and can only be exhibited for short periods of time. In this handy volume, however, two hundred and fifty images from one of the worlds greatest collections, The Pierpont Morgan Library, have been made accessible.

Given the stature of the Morgan collection, which in quality ranks with the half-dozen or so great national libraries of the Old World, one might assume that John Pierpont Morgan was the first to collect illuminated manuscripts in America. Nothing could be further from the truth, for the earliest illuminated manuscript recorded in America was the early fifteenth-century Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation), which Elihu Yale gave in 1714 to the college that bears his name. Nor was Morgan the first to collect medieval manuscripts in New York, for the Union Theological Seminary had acquired thirty-seven manuscripts from Professor Leander van Ess in 1838. And, in November 1884, shortly after it was founded, the Grolier Club held what was probably the first exhibition of illuminated manuscripts in America. Eight years later a larger exhibition was held, this time with a catalog, indicating the rising number of collectors. These collectors included Robert Hoe and Henry Walters, the latter having acquired his first manuscript (a Book of Hours) by 1895, when he both became a member of the Grolier Club and received his inheritance.

Morgan, however, was not yet among these, for he did not start collecting on a large scale until after his fathers death in 1890, when he acquired the means to do so. Even then, he did not become a member of the Grolier Club until 1897. And his first documented manuscript with full-page miniatures was not medieval at all, but an early nineteenth-century Ragamala (M.211) made in Jaipur. It came with the purchase of James Tooveys collection of bindings and books on June 2, 1899, which also included six Western manuscripts (two were fifteenth-century humanist manuscripts [M.118, M.244]; one, a seventeenth-century copy of Les douze empereurs [M.121], or The Twelve Caesars, did contain portrait busts). The Toovey collection, referred to by contemporaries as a "Library of Leather and Literature, was, in fact, purchased for its bindings and early printed books. Morgan had already been inclined toward fine bindings, having tried his hand at bookbinding as a teenager. The Ragamala was evidently part of the Toovey collection on account of its gold embroidered silk binding.

The real cornerstone of the medieval collection, however, was laid following a cable sent on July 4, 1899, to Pierpont Morgan by his precocious book-collecting nephew, Junius Spencer Morgan. In the cable Junius informed his uncle that he could obtain for him a famous ninth-century Gospels in a jeweled binding, a treasure unequaled in France or England, for ten thousand pounds. Morgan wisely took his nephews advice and purchased the manuscript. Known as the Lindau Gospels (after the location of the Swabian convent that once owned it on the island of Lindau on Lake Constance), it became Morgans first major illuminated manuscript. Its number is easy to remember, for it is M.1. The manuscript was written at the Swiss Abbey of St. Gall at the end of the ninth century, but the two covers, which were added later, were made elsewhere. The front cover, made about 880 in one of the imperial workshops of Charles the Bald, is one of the finest examples of Carolingian goldsmith work, while the back cover was made about a century earlier, probably in Salzburg, Austria.

Evidently inspired by this auspicious beginning, Morgan again took his nephews advice and purchased, in 1900, the library of Theodore Irwin (of Oswego, New York). Among the several thousand books were sixteen manuscripts, including the Golden Gospels of Henry VIII (M.23) and a French Apocalypse (M.133, see pages 76-77) of about 1415 made for Jean, duc de Berry, the most famous patron of illumination in the early fifteenth century.

The most important bulk purchase, however, was made during the summer of 1902, when Morgan acquired the impressive collection of Richard Bennett of Manchester. The seven hundred volumes included thirty-two books printed by William Caxton (the first English printer) and 110 manuscripts, thirty of which had belonged to William Morris. Important English manuscripts included the late twelfth-century Worksop Bestiary (M.81, pages 218-219, and 244) and the late thirteenth-century Windmill Psalter. As before, the collection was purchased through Junius Spencer Morgan. Indeed, the important role played by Junius has not been sufficiently made known, and it is tempting to suggest that without him, Morgan might never have collected manuscripts at all, or at least not on the same scale. The Bennett collection provided Morgan with a nucleus around which to build.

Although it is often assumed that Morgan purchased everything in bulk, this is hardly the case for the manuscripts. In fact, the total number of manuscripts that came as parts of collections was only slightly less than the 144 Ludwig manuscripts that formed the nucleus for the manuscript collection of The J. Paul Getty Museum. Normally, manuscripts were acquired singly or in small groups. The celebrated Book of Hours illuminated by Giulio Clovio for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese is a case in point (M.69, pages 24-25, 32, 55, 61, 216-217, and 277). It was offered by the Frankfurt firm of Goldschmidt in 1903, while Morgan was taking the cure at Aix-les-Bains. The manuscript had everything going for it: beauty, fame, importance, distinguished provenance, and even a binding then attributed to Cellini. Vasari, in his Lives of the Painters, described each of its full-page miniatures, regarding it as one of the sights of Rome. Morgan was so pleased with the manuscript that, uncharacteristically, he took it with him personally rather than have it sent.

Meanwhile, the construction of Morgans library (1902-6) by the firm of McKim, Mead, and White had begun, and it was clear that Morgan would soon need a librarian. Here again, it was Junius who brought Belle da Costa Greene to the attention of Morgan. She had, at the time, been working in the library of Princeton University. Arriving in 1905, Greene soon became Morgans trusted aid, playing a pivotal role in developing the collection of manuscripts. By Morgans death in 1913 about six hundred manuscripts had been assembled, and these already constituted the most important collection in America. The justly famous Da Costa Hours (M.399, pages 54, 109, 162, 180, and 195-199), acquired in 1907, was not, as one might assume, named after Belle da Costa Greene, but after its second owner, Don Alvaro Da Costa, the armorer of King Manuel I of Portugal. It was illuminated in Bruges about 1515 by Simon Bening, the last great Flemish illuminator.

After Morgans death, his son, J. P. (Jack) Morgan, Jr., retained Belle Greene as librarian. Although Jack had assured her that acquisitions would continue after World War I, she purchased, in 1916, and apparently on her own initiative, the Librarys celebrated Old Testament Miniatures (M.638, pages 26-27, 136, and 150). It is also known as the Maciejowski or Shah Abbas Bible because Cardinal Bernard Maciejowski sent it to Isfahan as part of a papal mission organized by Clement VIII, which presented it to the shah in 1608. Belle Greene must have been quite relieved when she wrote to Sidney Cockerell on December 12, 1916, that the younger "Mr. Morgan was quite keen to see the manuscript and that he quite thoroughly approves of my purchasing it-which is a good omen (for me) and, I would add, for the Morgan Library. The manuscript, Jacks first major acquisition, thus provided an important turning point and represented a line of continuity, for the book had already been offered to his father in 1910. Even though Belle Greene did not realize that the manuscript was probably made for King Louis IX, she recognized its importance and did not want to lose it a second time. One of the greatest French manuscripts of the thirteenth century, it contains in its eighty-six pages about three hundred scenes; the scale and elaboration of the Old Testament cycle, which begins with the Creation and ends with King David, is without parallel.

In 1924, Jack, realizing that the collection had become too important to remain in private hands, founded The Pierpont Morgan Library in memory of his fathers love of rare books, naming Belle da Costa Greene its first director. Although Jack added only two hundred manuscripts, they were of the highest quality and importance. Whereas most of the manuscripts purchased by his father dated from the twelfth to the sixteenth century, he pushed the range back to the eighth century and added Byzantine manuscripts as well.

Among the last were the Librarys two finest Byzantine manuscripts: a mid-tenth-century copy of De materia medica of Dioscorides (M.652); and a late-eleventh-century Lectionary made in Constantinople (M.639, page 91). Significant Western additions included the earliest illustrated Beatus Apocalypse (M.644, pages 82-84), illuminated by Maius about 950 (1919); The Berthold Sacramentary (M.710, pages 44, 95, and 264), the most luxurious German manuscript of the early thirteenth century (1926); The Psalter and Book of Hours of Yolande de Soissons (M.729, pages 48, 67, 110, and 175), one of the richest illustrated French manuscripts of the late thirteenth century (1927); a fragmentary Book of Hours (M.732, pages 41 and 210-211) illuminated by Jean Bourdichon (1927); and the Life, Passion, and Miracles of St. Edmund (M.736, pages 122 and 140) of about 1130, one of the earliest illustrated lives of an English saint (1927). It should be pointed out that even after the Library was founded in 1924, Jack continued to purchase expensive manuscripts for the Library, especially those mentioned above.

Six years after Jacks death in 1943, the Librarys second director, Frederick B. Adams, Jr., founded the Association of Fellows, a group of interested supporters who made possible the continued growth of the collection, both by gifts in kind and cash. The first major manuscript acquired with the assistance of the Fellows was a Book of Hours (M.834, page 68) illuminated by Jean Fouquet (later completed by Jean Colombe), the most important fifteenth-century French painter (1950). A second important acquisition was half of the celebrated Hours of Catherine of Cleves (M.917, pages 50, 100-105, 190-91, and 233) a peerless Dutch Book of Hours (1963); it was made in Utrecht about 1440. The other half (M.945, pages 232, 263, and 268) was purchased (1970) under the third director, Charles Ryskamp, who also acquired in the same year the Prayer Book (M.944, page 98) painted by Michelino da Bezosso in Milan about 1420, his masterpiece.

In 1983 Clara S. Peck bequeathed her richly illustrated manuscript of Gaston Phébuss Livre de la chasse (M.1044, pages 167, 169, 186-88, and 228-31), illuminated in Paris about 1410. But the most significant gift of manuscripts to the Library came the following year, when it received the William S. Glazier Collection of seventy-five manuscripts (for example see G.25, pages 34 and 141, and G.44, pages 42, 56, and 70), until then the most important collection in private hands. In 1985, with the death of Curt F. Bühler, for many years the Librarys Keeper of Printed Books, the Library received his collection of sixty manuscripts. Two more large bequests were made under the current director, Charles E. Pierce, Jr.: the E. Clark Stillman Collection brought twenty-one manuscripts and the Julia P. Wightman Collection contained thirty-six. Thanks to the continued support of the Fellows and Friends of the Library, the collection has continued to grow, now numbering nearly thirteen hundred manuscripts.

This Tiny Folio is arranged thematically, to reflect the structure of medieval and Renaissance life and its concerns: biblical scenes; saints, rites, and rituals; royalty, pastimes, and professions; flora and fauna; and the supernatural. Although this mini-museum of pictures represents but a minuscule proportion of all that the Morgan manuscripts contain, it may serve to open the door, if slightly, to a vast world of pictorial possibility, surprise, and insight

It is generally acknowledged that Pierpont Morgan was the greatest collector of our century. Within a period of some twenty years before his death in 1913, he assembled vast collections of antiquities, paintings, sculptures, tapestries, porcelains, watches, and other decorative objects. But none of these was to find a permanent home in The Pierpont Morgan Library. That building, commissioned from Charles McKim in 1902 and finished in 1906, was destined to house the collections that were evidently closest to his heart: autograph manuscripts, rare books and bindings, old master drawings, Mesopotamian cylinder seals, papyri, and medieval and Renaissance manuscripts. Of these, it is perhaps the last for which the Library is best known.

Pierponts son, Jack, who founded the Morgan Library in 1924, made important additions until his death in 1943. The present volume, which includes many manuscripts acquired since 1943, conveys the full range and quality of the collection as it now exists. By making accessible to a larger audience the delights of an art form usually buried in closed books, this volume also helps fulfill the goals of the founders.

Charles E. Pierce, Jr.

Director, The Pierpont Morgan Library

Introduction

Medieval and Renaissance illuminated manuscripts are many-splendored things, objects of both great beauty and tremendous pictorial variety and richness. They are like museums between the covers of books and constitute the largest surviving body of painting from this period. Because the pictures have been protected by bindings, their incredible freshness has been preserved and they have avoided the vicissitudes suffered by panel and wall painting. Since the miniatures have been largely spared from the hand of the restorer, they provide the most reliable resource for the study of medieval and Renaissance color. But since they are parts of books much can also be learned about how earlier men and women lived, what they wrote, read, and thought, and how they used and contributed to knowledge. One can also observe the different ways in which books were written, decorated, and bound over the centuries. The specific subjects selected, the nature of their representations, and the size of their illustrations are also telling.

The types of books, too, speak much about the medieval citizens personal concerns. Aside from Bibles, there are all kinds of service books, such as Sacramentaries, Missals, Lectionaries, Graduals, Breviaries, Antiphonaries, Psalters, and Books of Hours; various theological works and commentaries; and lives of the saints and other forms of devotional literature. There are scientific manuscripts dealing with astrology, astronomy, medicine, plants, animals, and minerals; and works of a more practical nature telling when and how to plant, how to take care of horses and dogs, how to hunt and fight. There are works of historical interest, such as biographies and chronicles, and texts dealing with law, exploration, and cartography. And there are books for edification, such as works by classical authors, and works for pleasure, such as the medieval romances. The images in such manuscripts are incredibly varied, however, and have remained largely hidden and little known. Furthermore, they are also light sensitive and can only be exhibited for short periods of time. In this handy volume, however, two hundred and fifty images from one of the worlds greatest collections, The Pierpont Morgan Library, have been made accessible.

Given the stature of the Morgan collection, which in quality ranks with the half-dozen or so great national libraries of the Old World, one might assume that John Pierpont Morgan was the first to collect illuminated manuscripts in America. Nothing could be further from the truth, for the earliest illuminated manuscript recorded in America was the early fifteenth-century Speculum humanae salvationis (Mirror of Human Salvation), which Elihu Yale gave in 1714 to the college that bears his name. Nor was Morgan the first to collect medieval manuscripts in New York, for the Union Theological Seminary had acquired thirty-seven manuscripts from Professor Leander van Ess in 1838. And, in November 1884, shortly after it was founded, the Grolier Club held what was probably the first exhibition of illuminated manuscripts in America. Eight years later a larger exhibition was held, this time with a catalog, indicating the rising number of collectors. These collectors included Robert Hoe and Henry Walters, the latter having acquired his first manuscript (a Book of Hours) by 1895, when he both became a member of the Grolier Club and received his inheritance.

Morgan, however, was not yet among these, for he did not start collecting on a large scale until after his fathers death in 1890, when he acquired the means to do so. Even then, he did not become a member of the Grolier Club until 1897. And his first documented manuscript with full-page miniatures was not medieval at all, but an early nineteenth-century Ragamala (M.211) made in Jaipur. It came with the purchase of James Tooveys collection of bindings and books on June 2, 1899, which also included six Western manuscripts (two were fifteenth-century humanist manuscripts [M.118, M.244]; one, a seventeenth-century copy of Les douze empereurs [M.121], or The Twelve Caesars, did contain portrait busts). The Toovey collection, referred to by contemporaries as a "Library of Leather and Literature, was, in fact, purchased for its bindings and early printed books. Morgan had already been inclined toward fine bindings, having tried his hand at bookbinding as a teenager. The Ragamala was evidently part of the Toovey collection on account of its gold embroidered silk binding.

The real cornerstone of the medieval collection, however, was laid following a cable sent on July 4, 1899, to Pierpont Morgan by his precocious book-collecting nephew, Junius Spencer Morgan. In the cable Junius informed his uncle that he could obtain for him a famous ninth-century Gospels in a jeweled binding, a treasure unequaled in France or England, for ten thousand pounds. Morgan wisely took his nephews advice and purchased the manuscript. Known as the Lindau Gospels (after the location of the Swabian convent that once owned it on the island of Lindau on Lake Constance), it became Morgans first major illuminated manuscript. Its number is easy to remember, for it is M.1. The manuscript was written at the Swiss Abbey of St. Gall at the end of the ninth century, but the two covers, which were added later, were made elsewhere. The front cover, made about 880 in one of the imperial workshops of Charles the Bald, is one of the finest examples of Carolingian goldsmith work, while the back cover was made about a century earlier, probably in Salzburg, Austria.

Evidently inspired by this auspicious beginning, Morgan again took his nephews advice and purchased, in 1900, the library of Theodore Irwin (of Oswego, New York). Among the several thousand books were sixteen manuscripts, including the Golden Gospels of Henry VIII (M.23) and a French Apocalypse (M.133, see pages 76-77) of about 1415 made for Jean, duc de Berry, the most famous patron of illumination in the early fifteenth century.

The most important bulk purchase, however, was made during the summer of 1902, when Morgan acquired the impressive collection of Richard Bennett of Manchester. The seven hundred volumes included thirty-two books printed by William Caxton (the first English printer) and 110 manuscripts, thirty of which had belonged to William Morris. Important English manuscripts included the late twelfth-century Worksop Bestiary (M.81, pages 218-219, and 244) and the late thirteenth-century Windmill Psalter. As before, the collection was purchased through Junius Spencer Morgan. Indeed, the important role played by Junius has not been sufficiently made known, and it is tempting to suggest that without him, Morgan might never have collected manuscripts at all, or at least not on the same scale. The Bennett collection provided Morgan with a nucleus around which to build.

Although it is often assumed that Morgan purchased everything in bulk, this is hardly the case for the manuscripts. In fact, the total number of manuscripts that came as parts of collections was only slightly less than the 144 Ludwig manuscripts that formed the nucleus for the manuscript collection of The J. Paul Getty Museum. Normally, manuscripts were acquired singly or in small groups. The celebrated Book of Hours illuminated by Giulio Clovio for Cardinal Alessandro Farnese is a case in point (M.69, pages 24-25, 32, 55, 61, 216-217, and 277). It was offered by the Frankfurt firm of Goldschmidt in 1903, while Morgan was taking the cure at Aix-les-Bains. The manuscript had everything going for it: beauty, fame, importance, distinguished provenance, and even a binding then attributed to Cellini. Vasari, in his Lives of the Painters, described each of its full-page miniatures, regarding it as one of the sights of Rome. Morgan was so pleased with the manuscript that, uncharacteristically, he took it with him personally rather than have it sent.

Meanwhile, the construction of Morgans library (1902-6) by the firm of McKim, Mead, and White had begun, and it was clear that Morgan would soon need a librarian. Here again, it was Junius who brought Belle da Costa Greene to the attention of Morgan. She had, at the time, been working in the library of Princeton University. Arriving in 1905, Greene soon became Morgans trusted aid, playing a pivotal role in developing the collection of manuscripts. By Morgans death in 1913 about six hundred manuscripts had been assembled, and these already constituted the most important collection in America. The justly famous Da Costa Hours (M.399, pages 54, 109, 162, 180, and 195-199), acquired in 1907, was not, as one might assume, named after Belle da Costa Greene, but after its second owner, Don Alvaro Da Costa, the armorer of King Manuel I of Portugal. It was illuminated in Bruges about 1515 by Simon Bening, the last great Flemish illuminator.

After Morgans death, his son, J. P. (Jack) Morgan, Jr., retained Belle Greene as librarian. Although Jack had assured her that acquisitions would continue after World War I, she purchased, in 1916, and apparently on her own initiative, the Librarys celebrated Old Testament Miniatures (M.638, pages 26-27, 136, and 150). It is also known as the Maciejowski or Shah Abbas Bible because Cardinal Bernard Maciejowski sent it to Isfahan as part of a papal mission organized by Clement VIII, which presented it to the shah in 1608. Belle Greene must have been quite relieved when she wrote to Sidney Cockerell on December 12, 1916, that the younger "Mr. Morgan was quite keen to see the manuscript and that he quite thoroughly approves of my purchasing it-which is a good omen (for me) and, I would add, for the Morgan Library. The manuscript, Jacks first major acquisition, thus provided an important turning point and represented a line of continuity, for the book had already been offered to his father in 1910. Even though Belle Greene did not realize that the manuscript was probably made for King Louis IX, she recognized its importance and did not want to lose it a second time. One of the greatest French manuscripts of the thirteenth century, it contains in its eighty-six pages about three hundred scenes; the scale and elaboration of the Old Testament cycle, which begins with the Creation and ends with King David, is without parallel.

In 1924, Jack, realizing that the collection had become too important to remain in private hands, founded The Pierpont Morgan Library in memory of his fathers love of rare books, naming Belle da Costa Greene its first director. Although Jack added only two hundred manuscripts, they were of the highest quality and importance. Whereas most of the manuscripts purchased by his father dated from the twelfth to the sixteenth century, he pushed the range back to the eighth century and added Byzantine manuscripts as well.

Among the last were the Librarys two finest Byzantine manuscripts: a mid-tenth-century copy of De materia medica of Dioscorides (M.652); and a late-eleventh-century Lectionary made in Constantinople (M.639, page 91). Significant Western additions included the earliest illustrated Beatus Apocalypse (M.644, pages 82-84), illuminated by Maius about 950 (1919); The Berthold Sacramentary (M.710, pages 44, 95, and 264), the most luxurious German manuscript of the early thirteenth century (1926); The Psalter and Book of Hours of Yolande de Soissons (M.729, pages 48, 67, 110, and 175), one of the richest illustrated French manuscripts of the late thirteenth century (1927); a fragmentary Book of Hours (M.732, pages 41 and 210-211) illuminated by Jean Bourdichon (1927); and the Life, Passion, and Miracles of St. Edmund (M.736, pages 122 and 140) of about 1130, one of the earliest illustrated lives of an English saint (1927). It should be pointed out that even after the Library was founded in 1924, Jack continued to purchase expensive manuscripts for the Library, especially those mentioned above.

Six years after Jacks death in 1943, the Librarys second director, Frederick B. Adams, Jr., founded the Association of Fellows, a group of interested supporters who made possible the continued growth of the collection, both by gifts in kind and cash. The first major manuscript acquired with the assistance of the Fellows was a Book of Hours (M.834, page 68) illuminated by Jean Fouquet (later completed by Jean Colombe), the most important fifteenth-century French painter (1950). A second important acquisition was half of the celebrated Hours of Catherine of Cleves (M.917, pages 50, 100-105, 190-91, and 233) a peerless Dutch Book of Hours (1963); it was made in Utrecht about 1440. The other half (M.945, pages 232, 263, and 268) was purchased (1970) under the third director, Charles Ryskamp, who also acquired in the same year the Prayer Book (M.944, page 98) painted by Michelino da Bezosso in Milan about 1420, his masterpiece.

In 1983 Clara S. Peck bequeathed her richly illustrated manuscript of Gaston Phébuss Livre de la chasse (M.1044, pages 167, 169, 186-88, and 228-31), illuminated in Paris about 1410. But the most significant gift of manuscripts to the Library came the following year, when it received the William S. Glazier Collection of seventy-five manuscripts (for example see G.25, pages 34 and 141, and G.44, pages 42, 56, and 70), until then the most important collection in private hands. In 1985, with the death of Curt F. Bühler, for many years the Librarys Keeper of Printed Books, the Library received his collection of sixty manuscripts. Two more large bequests were made under the current director, Charles E. Pierce, Jr.: the E. Clark Stillman Collection brought twenty-one manuscripts and the Julia P. Wightman Collection contained thirty-six. Thanks to the continued support of the Fellows and Friends of the Library, the collection has continued to grow, now numbering nearly thirteen hundred manuscripts.

This Tiny Folio is arranged thematically, to reflect the structure of medieval and Renaissance life and its concerns: biblical scenes; saints, rites, and rituals; royalty, pastimes, and professions; flora and fauna; and the supernatural. Although this mini-museum of pictures represents but a minuscule proportion of all that the Morgan manuscripts contain, it may serve to open the door, if slightly, to a vast world of pictorial possibility, surprise, and insight

Descriere

Glorious works of art as well as chronicles of a past age, illuminated manuscripts supply some of the finest and best-preserved evidence of what life was like during the medieval and Renaissance periods. This little Tiny Folios book contains spectacular examples of early book illustration from one of the greatest libraries of illuminated manuscripts in the world. 240 full-color illus.