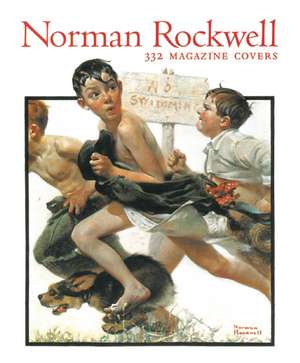

Norman Rockwell: 332 Magazine Covers: Tiny Folio

Autor Christopher Finchen Limba Engleză Hardback – iul 2013

Norman Rockwell's best-loved works, collected in a handsome clothbound volume

Norman Rockwell gave us a picture of America that was familiar—astonishingly so—and at the same time unique, because only he could bring it to life with such authority.

Rockwell best expressed this vision of America in his justly famous cover illustrations for the Saturday Evening Post, painted between 1916 and 1963. All of his Post covers are reproduced in splendid full color in this oversized volume, with commentaries by Christopher Finch, the noted writer on art and popular culture.

Norman Rockwell gave us a picture of America that was familiar—astonishingly so—and at the same time unique, because only he could bring it to life with such authority.

Rockwell best expressed this vision of America in his justly famous cover illustrations for the Saturday Evening Post, painted between 1916 and 1963. All of his Post covers are reproduced in splendid full color in this oversized volume, with commentaries by Christopher Finch, the noted writer on art and popular culture.

Din seria Tiny Folio

-

Preț: 74.82 lei

Preț: 74.82 lei -

Preț: 68.68 lei

Preț: 68.68 lei -

Preț: 75.01 lei

Preț: 75.01 lei -

Preț: 75.01 lei

Preț: 75.01 lei -

Preț: 75.88 lei

Preț: 75.88 lei -

Preț: 75.64 lei

Preț: 75.64 lei -

Preț: 68.93 lei

Preț: 68.93 lei -

Preț: 68.99 lei

Preț: 68.99 lei -

Preț: 68.73 lei

Preț: 68.73 lei -

Preț: 77.11 lei

Preț: 77.11 lei -

Preț: 68.78 lei

Preț: 68.78 lei -

Preț: 61.76 lei

Preț: 61.76 lei -

Preț: 62.83 lei

Preț: 62.83 lei -

Preț: 66.78 lei

Preț: 66.78 lei -

Preț: 69.05 lei

Preț: 69.05 lei - 19%

Preț: 28.20 lei

Preț: 28.20 lei -

Preț: 59.55 lei

Preț: 59.55 lei -

Preț: 68.46 lei

Preț: 68.46 lei - 20%

Preț: 55.20 lei

Preț: 55.20 lei - 24%

Preț: 50.75 lei

Preț: 50.75 lei - 21%

Preț: 53.59 lei

Preț: 53.59 lei - 20%

Preț: 55.20 lei

Preț: 55.20 lei - 6%

Preț: 65.00 lei

Preț: 65.00 lei -

Preț: 68.84 lei

Preț: 68.84 lei

Preț: 379.29 lei

Preț vechi: 426.17 lei

-11% Nou

Puncte Express: 569

Preț estimativ în valută:

72.60€ • 78.89$ • 61.02£

72.60€ • 78.89$ • 61.02£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 31 martie-14 aprilie

Livrare express 14-20 martie pentru 154.40 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789211446

ISBN-10: 0789211440

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: colour illustrations

Dimensiuni: 279 x 330 x 47 mm

Greutate: 3.57 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Tiny Folio

ISBN-10: 0789211440

Pagini: 400

Ilustrații: colour illustrations

Dimensiuni: 279 x 330 x 47 mm

Greutate: 3.57 kg

Ediția:New.

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Tiny Folio

Cuprins

Table of Contents from Norman Rockwell: 332 Magazine Covers

Norman Rockwell Portrayed Americans as Americans Chose to See Themselves

Color Plates

Catalog of Covers

Norman Rockwell Portrayed Americans as Americans Chose to See Themselves

Color Plates

Catalog of Covers

Notă biografică

Christopher Finch was born in Guernsey, Channel Islands, in 1939 and came to the United States in 1968 to join the curatorial staff of the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis. His books include the best sellers Norman Rockwell’s America, The Art of Walt Disney, and Rainbow, a biography of Judy Garland, which was turned into a motion picture for NBC television.

Extras

Excerpt from Norman Rockwell: 332 Magazine Covers

Norman Rockwell Portrayed Americans as Americans Chose to See Themselves

Norman Rockwell began his career as an illustrator in 1910, the year that Mark Twain died. He sold his first cover paintings when there were still horse-drawn cabs on the streets of many American cities, and he began his association with The Saturday Evening Post in 1916, the year in which Woodrow Wilson was elected to a second term in the White House and the year in which Chaplin's movie The Floorwalker broke box office records across the country. Young women were enjoying the comparative freedom of ankle-length skirts, and their beaux were serenading them with such immortal ditties as “The Sunshine of Your Smile” and “Yackie Hacki Wicki Wackie Woo.” In literature this was the age of Booth Tarkington, Edith Wharton, and O. Henry. Ernest Hemingway, still in his teens, was a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star, and F. Scott Fitzgerald—soon to become a frequent contributor to the Post—was still at Princeton. The New York Armory show of 1913 had introduced the American public to recent trends in European painting, but traditional values still reigned supreme in the American art world. Only a handful of artists aspired to anything more novel than the mild postimpressionism of painters like John Sloan and Maurice Prendergast. The movies were becoming a potent force in popular entertainment, but few people took them seriously or thought they might one day take their place alongside established art forms.

It was a world in transition, but the transition had not yet accelerated to the giddy speed it would achieve in the twenties. People could be thrilled by the exploits of pioneer aviators without being conscious of the impact that flying machines would have on modern warfare. It was possible to enjoy the conveniences provided by such relatively new inventions as the telephone, the phonograph, the vacuum cleaner, and the automobile without being too troubled by the notion that technology might someday soon threaten the established order of things.

The illustrator and cover artist working in the mid-teens of the twentieth century was generally asked to embody established values. The latest model Hupmobile Runabout might well be the subject of a given picture—an advertisement, perhaps—but the people who were shown admiring or driving in the newfangled vehicle were presumed to espouse the same values as their parents and their grandparents. The set of the jaw, the glint in the eye had not changed much since the middle of the nineteenth century. The women wore their hair a little differently, perhaps, and men were doing without beards, but these are superficial differences. The fact is that the minds of the people who edited and bought magazines like Colliers, Country Gentleman, Literary Digest, and The Saturday Evening Post had been formed, to a large extent, in the Victorian era.

Norman Rockwell himself, born on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, had a classic late Victorian upbringing. He spent his childhood in a solidly middle-class, God-fearing household in which it was the custom for his father to read the works of Dickens out loud to the entire family. Thus Rockwell had little difficulty in adapting to the conventions that were current in the field of magazine illustration at the outset of his career. Although a New Yorker, he was especially drawn to rural subject matter (he is on record as saying that he felt more at home in the country). This reinforced his affection for traditional idioms, since it focused his attention on the most conservative elements of the population, those who were least susceptible to change of any kind.

In short, Rockwell began his career right in the mainstream of the illustrators of his day, sharing the assumptions and concerns of his contemporaries and of the editors who employed him. His work is remarkable because he sustained through half a century the values that he espoused in those early days when the world was changing more drastically than anyone could have imagined possible. It would be easy enough, of course, to find fault with his refusal to break with those values, but that would be unjust. Rockwell simply continued to believe in what he had always believed in, and in his own way, he did, in fact, change and grow throughout his career. He learned how to embrace the modern age without abandoning his own principles. But he was also forced to modify and enrich his approach to the art of illustration in order to reconcile those principles to a world that was evolving so fast it seemed, at times, on the verge of flying apart.

His earliest paintings are conventional, almost to the point of banality, because the values they embody could be taken so much for granted. As he was forced to deal with a changing environment, however, he was obliged to become more inventive and original. A situation that could be presented in the simplest of terms in 1916, for example, might still be valid a quarter of a century later, but only if it were made more specific. Stereotypes had to be replaced by carefully individualized characters. More and more detail had to be introduced to make a situation more particular. As time passed, Rockwell was called upon to draw on all his resources as an illustrator in order to put his audience—which was always changing—along with him. As circumstances became, theoretically at least, more hostile to his kind of traditional image-making, he rose to the challenge. His work became richer and more resonant, reaching a peak in the forties and fifties when most of the men who had been his rivals at the outset of his career were already long forgotten. His most remarkable quality was his ability to grow and adapt—to remain flexible—without ever modifying the basic tenets of his art.

What seems to have enabled him to do this was a belief in the fundamental decency of the great majority of his fellow human beings. This belief was the most deep-seated of all his values, and it enabled him to perceive a continuity in behavior patterns undisturbed by shifts in social mores. The twentieth century has offered plenty of evidence of man's ability to shed his humanity, and Rockwell was certainly aware of this, yet he clung to his belief and decency. It was an article of faith, and it gave his work its particular flavor of innocence.

Over the past hundred years or so, artists and critics have been ambiguous in their attitudes toward innocence. The "naive" vision of such painters as Henri Rousseau has been much prized, yet more schooled artists have often been led astray when they attempted to embrace such a vision (indeed it would be difficult for such a vision to survive schooling). Picasso, the most protean of all twentieth-century artists—greatly admired by Rockwell, it should be noted—was able to run the full gamut: from a childlike delight in transforming bicycle parts into the likeness of a bulls head to the nightmare vision of Guernica—but Picasso was, in every way, an exception to the rules.

Rockwell's art has nothing, of course, to do with the innovations of modern painting. He was essentially a popular artist—an entertainer—and he was always fully aware that his work was intended to be seen in reproduction. The originals—generally painted on a relatively large scale—are, however, beautiful objects in their own right. He was looking to the general public rather than to a small, highly informed audience, and it was this perhaps that enabled him to sustain the innocence of his vision. Dealing with mass communication rather than the higher reaches of aesthetic decision-making, he has no place in the developing pattern of art history. It is futile even to compare him with American realists like Edward Hopper, whose subject matter occasionally had something in common with Rockwell's. Hopper was always concerned primarily with plastic values, as is the case with any "pure" painter. Rockwell, on the other hand, had to think first and foremost about conveying information about his subject, as must be the case with any illustrator. An illustrator may, of course, have many of the same skills as the "pure" painter, but he deploys them in a different way. Essentially he borrows from existing idioms of easel painting—whether traditional, as in Norman Rockwell's case, or more experimental, as was the case with his notable contemporary Rockwell Kent—and uses them as a means of conveying information. Interestingly, it is known that Norman Rockwell himself, during the twenties, was drawn to modern idioms-the result of a sojourn in Paris—but rejected them in favor of older conventions. The reason for this, we may suppose, was his recognition of the fact that his gift was not painterly at all (remarkable as his painterly skills were). It was, rather, his ability as a pictorial storyteller.

Most of Rockwell's finest covers are, in effect, anecdotes. With occasional exceptions, he can give us only one scene—an isolated episode—but, in his mature work especially, he knows how to pack that scene with so much significant detail that the events that precede it, and follow from it, are, so to speak, latent in the single image. A great short story writer, like Guy de Maupassant, can conjure up a whole life within the span of a dozen pages. Rockwell, at his best, was capable of doing the same kind of thing with a single picture. Because of this he deserves to be thought of as something more than just an illustrator. An illustrator, by definition, is someone who takes another person's story (or advertising copy) and adds a visual dimension. Rockwell, in his cover art, went far beyond this. He was not only the illustrator, but also the author of the story. In his work, image and anecdote were inseparable; each sprang naturally from the other…

Norman Rockwell Portrayed Americans as Americans Chose to See Themselves

Norman Rockwell began his career as an illustrator in 1910, the year that Mark Twain died. He sold his first cover paintings when there were still horse-drawn cabs on the streets of many American cities, and he began his association with The Saturday Evening Post in 1916, the year in which Woodrow Wilson was elected to a second term in the White House and the year in which Chaplin's movie The Floorwalker broke box office records across the country. Young women were enjoying the comparative freedom of ankle-length skirts, and their beaux were serenading them with such immortal ditties as “The Sunshine of Your Smile” and “Yackie Hacki Wicki Wackie Woo.” In literature this was the age of Booth Tarkington, Edith Wharton, and O. Henry. Ernest Hemingway, still in his teens, was a cub reporter for the Kansas City Star, and F. Scott Fitzgerald—soon to become a frequent contributor to the Post—was still at Princeton. The New York Armory show of 1913 had introduced the American public to recent trends in European painting, but traditional values still reigned supreme in the American art world. Only a handful of artists aspired to anything more novel than the mild postimpressionism of painters like John Sloan and Maurice Prendergast. The movies were becoming a potent force in popular entertainment, but few people took them seriously or thought they might one day take their place alongside established art forms.

It was a world in transition, but the transition had not yet accelerated to the giddy speed it would achieve in the twenties. People could be thrilled by the exploits of pioneer aviators without being conscious of the impact that flying machines would have on modern warfare. It was possible to enjoy the conveniences provided by such relatively new inventions as the telephone, the phonograph, the vacuum cleaner, and the automobile without being too troubled by the notion that technology might someday soon threaten the established order of things.

The illustrator and cover artist working in the mid-teens of the twentieth century was generally asked to embody established values. The latest model Hupmobile Runabout might well be the subject of a given picture—an advertisement, perhaps—but the people who were shown admiring or driving in the newfangled vehicle were presumed to espouse the same values as their parents and their grandparents. The set of the jaw, the glint in the eye had not changed much since the middle of the nineteenth century. The women wore their hair a little differently, perhaps, and men were doing without beards, but these are superficial differences. The fact is that the minds of the people who edited and bought magazines like Colliers, Country Gentleman, Literary Digest, and The Saturday Evening Post had been formed, to a large extent, in the Victorian era.

Norman Rockwell himself, born on the Upper West Side of Manhattan, had a classic late Victorian upbringing. He spent his childhood in a solidly middle-class, God-fearing household in which it was the custom for his father to read the works of Dickens out loud to the entire family. Thus Rockwell had little difficulty in adapting to the conventions that were current in the field of magazine illustration at the outset of his career. Although a New Yorker, he was especially drawn to rural subject matter (he is on record as saying that he felt more at home in the country). This reinforced his affection for traditional idioms, since it focused his attention on the most conservative elements of the population, those who were least susceptible to change of any kind.

In short, Rockwell began his career right in the mainstream of the illustrators of his day, sharing the assumptions and concerns of his contemporaries and of the editors who employed him. His work is remarkable because he sustained through half a century the values that he espoused in those early days when the world was changing more drastically than anyone could have imagined possible. It would be easy enough, of course, to find fault with his refusal to break with those values, but that would be unjust. Rockwell simply continued to believe in what he had always believed in, and in his own way, he did, in fact, change and grow throughout his career. He learned how to embrace the modern age without abandoning his own principles. But he was also forced to modify and enrich his approach to the art of illustration in order to reconcile those principles to a world that was evolving so fast it seemed, at times, on the verge of flying apart.

His earliest paintings are conventional, almost to the point of banality, because the values they embody could be taken so much for granted. As he was forced to deal with a changing environment, however, he was obliged to become more inventive and original. A situation that could be presented in the simplest of terms in 1916, for example, might still be valid a quarter of a century later, but only if it were made more specific. Stereotypes had to be replaced by carefully individualized characters. More and more detail had to be introduced to make a situation more particular. As time passed, Rockwell was called upon to draw on all his resources as an illustrator in order to put his audience—which was always changing—along with him. As circumstances became, theoretically at least, more hostile to his kind of traditional image-making, he rose to the challenge. His work became richer and more resonant, reaching a peak in the forties and fifties when most of the men who had been his rivals at the outset of his career were already long forgotten. His most remarkable quality was his ability to grow and adapt—to remain flexible—without ever modifying the basic tenets of his art.

What seems to have enabled him to do this was a belief in the fundamental decency of the great majority of his fellow human beings. This belief was the most deep-seated of all his values, and it enabled him to perceive a continuity in behavior patterns undisturbed by shifts in social mores. The twentieth century has offered plenty of evidence of man's ability to shed his humanity, and Rockwell was certainly aware of this, yet he clung to his belief and decency. It was an article of faith, and it gave his work its particular flavor of innocence.

Over the past hundred years or so, artists and critics have been ambiguous in their attitudes toward innocence. The "naive" vision of such painters as Henri Rousseau has been much prized, yet more schooled artists have often been led astray when they attempted to embrace such a vision (indeed it would be difficult for such a vision to survive schooling). Picasso, the most protean of all twentieth-century artists—greatly admired by Rockwell, it should be noted—was able to run the full gamut: from a childlike delight in transforming bicycle parts into the likeness of a bulls head to the nightmare vision of Guernica—but Picasso was, in every way, an exception to the rules.

Rockwell's art has nothing, of course, to do with the innovations of modern painting. He was essentially a popular artist—an entertainer—and he was always fully aware that his work was intended to be seen in reproduction. The originals—generally painted on a relatively large scale—are, however, beautiful objects in their own right. He was looking to the general public rather than to a small, highly informed audience, and it was this perhaps that enabled him to sustain the innocence of his vision. Dealing with mass communication rather than the higher reaches of aesthetic decision-making, he has no place in the developing pattern of art history. It is futile even to compare him with American realists like Edward Hopper, whose subject matter occasionally had something in common with Rockwell's. Hopper was always concerned primarily with plastic values, as is the case with any "pure" painter. Rockwell, on the other hand, had to think first and foremost about conveying information about his subject, as must be the case with any illustrator. An illustrator may, of course, have many of the same skills as the "pure" painter, but he deploys them in a different way. Essentially he borrows from existing idioms of easel painting—whether traditional, as in Norman Rockwell's case, or more experimental, as was the case with his notable contemporary Rockwell Kent—and uses them as a means of conveying information. Interestingly, it is known that Norman Rockwell himself, during the twenties, was drawn to modern idioms-the result of a sojourn in Paris—but rejected them in favor of older conventions. The reason for this, we may suppose, was his recognition of the fact that his gift was not painterly at all (remarkable as his painterly skills were). It was, rather, his ability as a pictorial storyteller.

Most of Rockwell's finest covers are, in effect, anecdotes. With occasional exceptions, he can give us only one scene—an isolated episode—but, in his mature work especially, he knows how to pack that scene with so much significant detail that the events that precede it, and follow from it, are, so to speak, latent in the single image. A great short story writer, like Guy de Maupassant, can conjure up a whole life within the span of a dozen pages. Rockwell, at his best, was capable of doing the same kind of thing with a single picture. Because of this he deserves to be thought of as something more than just an illustrator. An illustrator, by definition, is someone who takes another person's story (or advertising copy) and adds a visual dimension. Rockwell, in his cover art, went far beyond this. He was not only the illustrator, but also the author of the story. In his work, image and anecdote were inseparable; each sprang naturally from the other…