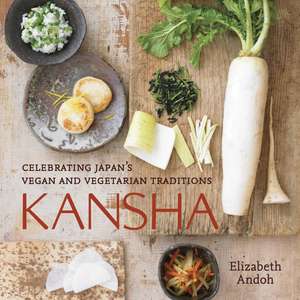

Kansha: Celebrating Japan's Vegan and Vegetarian Traditions

Autor Elizabeth Andohen Limba Engleză Hardback – 30 sep 2010

Vezi toate premiile Carte premiată

In these pages, with kansha as credo, Japan culinary authority Elizabeth Andoh offers more than 100 carefully crafted vegan recipes. She has culled classics from shōjin ryōri, or Buddhist temple cuisine (Creamy Sesame Pudding, Glazed Eel Look-Alike); gathered essentials of macrobiotic cooking (Toasted Hand-Pressed Brown Rice with Hijiki, Robust Miso); selected dishes rooted in history (Skillet-Scrambled Tofu with Leafy Greens, Pungent Pickles); and included inventive modern fare (Eggplant Sushi, Tōfu-Tōfu Burgers).

Andoh invites you to practice kansha in your own cooking, and she delights in demonstrating how “nothing goes to waste in the kansha kitchen.” In one especially satisfying example, she transforms each part of a single daikon—from the tapered tip to the tuft of greens, including the peels that most cooks would simply compost—into an array of wholesome, flavorful dishes.

Decades of living immersed in Japanese culture and years of culinary training have given Andoh a unique platform from which to teach. She shares her deep knowledge of the cuisine in the two-part A Guide to the Kansha Kitchen. In the first section, she explains basic cutting techniques, cooking methods, and equipment that will help you enhance flavor, eliminate waste, and speed meal preparation. In the second, Andoh demystifies ingredients that are staples in Japanese pantries, but may be new to you; they will boost your kitchen repertoire—vegan or omnivore—to new heights.

Stunning images by award-winning photographer Leigh Beisch complete Kansha, a pioneering volume sure to inspire as it instructs.

Preț: 186.07 lei

Preț vechi: 212.26 lei

-12% Nou

Puncte Express: 279

Preț estimativ în valută:

35.61€ • 37.13$ • 29.59£

35.61€ • 37.13$ • 29.59£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-07 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9781580089555

ISBN-10: 1580089550

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 40 4-COLOR PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 249 x 246 x 27 mm

Greutate: 1.4 kg

Editura: Ten Speed Press

ISBN-10: 1580089550

Pagini: 304

Ilustrații: 40 4-COLOR PHOTOS

Dimensiuni: 249 x 246 x 27 mm

Greutate: 1.4 kg

Editura: Ten Speed Press

Notă biografică

ELIZABETH ANDOH is the American authority on Japanese cuisine. She has made Japan her home since 1967 and divides her time between Tokyo and Osaka, directing a culinary program called A Taste of Culture. Her book Washoku won the 2006 IACP Jane Grigson award for distinguished scholarship in food writing and was nominated for a James Beard Award.

Extras

INTRODUCTION

Kansha means “appreciation,” an expression evident in many aspects of Japanese society and daily living. In a culinary context, the word acknowledges both nature’s bounty and the efforts and ingenuity of people who transform that abundance into marvelous food. In the kitchen and at table, in the supermarket and out in the gardens, fields, and waterways, kansha encourages us to prepare nutritionally sound and aesthetically satisfying meals that also avoid waste, conserve energy, and sustain our natural resources.

A keen appreciation of food does not require anyone to choose a plant-based diet, but it is in keeping with such a mindset. Kansha is about abundance—of grains, legumes, roots, shoots, leafy plants (aquatic and terrestrial), shrubs, herbs, berries, seeds, tree fruits and nuts—not abstinence (doing without meat, fish, poultry, eggs, or dairy). It is about nourishing ourselves with what nature provides, cleverly and respectfully applying human technique and technology in the process.

Kansha as both a concept and a practice is well integrated into Japanese culinary tradition. Indeed, it is one of several aspects of washoku, the ancient and indigenous food culture of Japan. Based on the notion that balancing color, flavor, and method of food preparation enables optimal nutrition and aesthetic satisfaction at table, the principles of washoku guide home cooks and food professionals alike to culinary harmony. As with my book Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen, I want this volume to both stimulate your intellect and satisfy your palate. And, as is true of washoku, I believe that kansha as a guiding principle in procuring, preparing, and partaking of food is universal in its appeal and application.

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON KANSHA

Buddhism, with its inherent respect for life that eschews consumption of animals, was first introduced to Japan by way of Korea in the sixth century. Among Japan’s varied food traditions, shōjin ryōri, most often translated as “Buddhist cuisine” or “temple cookery,” has become synonymous with vegetarian cooking. Indeed it is vegan, as no animal products are used. Shōjin ryōri became well established during the Kamakura period (1185ߝ1333), a tumultuous time in Japan’s history as feudal warlords vied for power. No doubt life was particularly perilous, and therefore seemed even more precious.

SHŌJIN RYŌRI The word shōjin means “earnest commitment.” Shōjin ryōri is not about dietary restrictions, but rather respect for nature’s bounty and for the diligence and ingenuity of those who procure it.

As you might expect, the earnest endeavor to prepare food shuns the use of shortcuts. The time and energy required to assemble a classic shōjin ryōri dish such as goma-dōfu, a creamy sesame pudding, is part of the reason it appears on temple vegetarian menus. It is undeniably delicious when prepared in the traditional time-consuming and physically exhausting manner, but there is a simpler way to make the pudding: using neri goma (toasted sesame paste), rather than parching, crushing, and grinding the seeds yourself in a suribachi (grooved mortar), a roughly two-hour workout guaranteed to tone your upper arms. In this book, I will be offering you both ways: the classic method for those who wish to experience appreciation through their own effort and labor, and the modern method for those pressed for time or with physical limitations—in which case, your appreciation can be focused on the ingenious efforts of others. Kansha, in this example, would be gratitude for artisanally produced pure toasted sesame paste.

ICHI MOTSU ZEN SHOKU The need to use food and energy resources as fully and effectively as possible led to many frugal culinary customs in Japan. The ecologically and nutritionally sound practice of ichi motsu zen shoku (one food, used entirely) encourages the use of all edible parts of plant foods: peels, roots, shoots, stems, seeds, and flowers. Throughout the book, I will be alerting you to opportunities for making fine food from the trimmed-away bits and pieces of produce that inevitably accumulate as you prepare a meal. You will soon discover that nothing goes to waste in the kansha kitchen.

KONDATÉ-ZUKUSHI Another longstanding Japanese culinary practice, kondaté-zukushi takes pleasure in making a meal from a single ingredient. This custom of using seasonally and regionally available foodstuffs developed in response to cyclical abundance amidst otherwise limited food resources. The well-established Japanese notion that a single ingredient, transformed in myriad ways, can become the highlight of a complete meal was the driving force behind the original (and flamboyant) Iron Chef television program.

Ancient approaches that remain applicable and meaningful to modern society, ichi motsu zen shoku and kondaté-zukushi will be evident throughout this book. At the conclusion of this introduction, in the section called Practicing Kansha, I will walk you through the preparation of Daikon-Zukushi, a menu celebrating the full glory of a plump, snowy white, green-tufted radish.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Since the 1970s, a number of social and dietary movements operating globally have combined to increase awareness of the benefits of adopting a vegetarian lifestyle. The modern macrobiotic movement, born in Japan and well traveled worldwide, has helped rekindle an interest in the ancient notion of food as medicine.

In Japan in the past decade, a growing consciousness of the importance of passing on Japanese culinary culture to future generations, combined with other food-related concerns, evolved into a grassroots movement known as shokuiku. The word itself, a combination of the calligraphy for “food” and for “education,” was coined by a group of food journalists to describe wide-ranging goals. Those aspirations included defining (and encouraging the adoption of) healthful dietary practices, recognizing the need to monitor safety in food production and distribution, and the training of young people’s palates to appreciate food prepared without chemical additives. In 2005, the shokuiku movement was formally recognized by the Japanese government’s Cabinet Office (Naikakufu), which influences policy and legislation in several key agencies, including the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Kōseisho); the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Nōrinsuisansho); and the Ministry of Education (Mombusho).

Current societal concerns with ecology (environmental pollution) and economics (pinched household budgets) have also led to a renewed interest in no-waste vegetarian cooking. In particular, a marketing concept known as LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability), which includes valuing organic farming over conventional methods, has become important in Japan’s contemporary food supply and distribution networks. Combined with the recent advent of the Slow Food movement and its respect for old-fashioned ways that encourage artisanal production, even urban dwellers have access to excellent processed foods that support a healthful, plant-focused diet.

The Japanese have also recently embraced induction heat (IH) cooking, a flameless way to prepare food in which heat is produced by magnetic fields. IH cooking is thought to be safer, less costly (after the initial investment for the special countertop cooker), and kinder to the environment. It does, however, place special requirements on cookware: the outer surface of pots, pans, and skillets must be ferrous—no glass, ceramic, aluminum, or copper, for example—and must come in direct, flat contact with the IH cooktop. But these requisites have not slowed the spread of this new cooking medium.

PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

My goal in writing Kansha is to empower you to create wholesome, nutritionally balanced, plant-based dishes, easily integrating preparation of these dishes into your busy and, most likely, urban daily routine.

Being able to consider the relative merits of one foodstuff or technique compared to another requires a comfortable familiarity with a wide range of products and kitchen skills. I will help you build that knowledge base, expanding your culinary horizons and repertoire by introducing you to an array of possibly unfamiliar foods and techniques that were developed in tandem with Japan’s vegetarian traditions. To help you become a practitioner-cook of kansha, I have included a detailed reference section, A Guide to the Kansha Kitchen, at the back of this book. It is divided into two parts, A Catalog of Tools and Techniques and A Catalog of Ingredients.

As a teacher of the Japanese culinary arts, I believe that the best recipes demonstrate how the culture as a whole approaches food preparation. My recipes will guide you to an understanding of why certain procedures are performed in the Japanese kitchen, then teach you when and how to do what needs to be done by advising you on timing, techniques, and relative proportion of ingredients to use. I will be encouraging you to adopt a mindful, considered approach to food preparation beginning with menu planning that eliminates unnecessary time and energy or superfluous foodstuffs.

PRACTICING KANSHA

Nothing goes to waste in the kansha kitchen. Putting this ideal into practice means fully using the food that nature provides, minimizing waste while maximizing eating pleasure.

Many fruits and vegetables come to market oddly shaped, slightly bruised, or a bit past prime, though still full of flavor and brimming with nutrients. What often ends up in the trash bin—seeds, fruit peels, vegetable trimmings, and misshapen or overripe produce—can be transformed into tasty side dishes. One approach is to mash, crush, grate, and/or blend the pulp of less-than-perfect produce to make soups, sauces, and aspics. Another approach is to finely shred or mince these usual castoffs, and make crispy fritters or crunchy pickles from them. You will find dozens of recipes throughout the book for using these usual kitchen scraps creatively, deliciously.

Packaged pantry goods such as soy sauce and miso do not spoil easily, though they do lose their aroma within a few weeks of opening. Refrigerating opened packages helps slow the loss, but after a month or so you’ll find such products lack verve. That’s when revitalizing them, changing them into flavor-enhancing condiments, makes sense. Having a jar of homemade vegan Seasoned Soy Concentrate (page 131) at the back of your refrigerator will be a boon on busy days, and Robust Miso (page 132) will perk up rice or dress up sticks of raw vegetables in a pinch. Once you get the hang of it, you will be surprised at how much you can do to reduce waste and improve flavor and nutrition. Think of the resulting dishes as a bonus for your resourcefulness.

One way to experience kansha in your own kitchen is to build an entire meal around a single vegetable, using it fully. Consider constructing a menu to celebrate a glorious daikon you find at your local farmers’ market. Title your meal Daikon-Zukushi: daikon in its entirety!

Different sections of daikon have different flavor and texture profiles. I suggest you use the leafy tops for making a confetti-like condiment to toss into cooked rice (Rice Tossed with Radish Greens, page 23). Then, divide the root portion into three segments: the neck (nearest the leafy tuft; this is often green), the midsection (usually bulbous and snowy white), and the tapered tip. Peel each segment and use the peels in various dishes, such as soup (Red and White Miso Soup, page 82) and a spicy sauté (Spicy Stir-Fry, page 122). Any leftover peels can be stored in a resealable bag and refrigerated for several days. To make a hearty main course, sear thick wheels of daikon from the neck portion in a skillet, glazing them lightly with a sweetened soy sauce before topping with citrus peel slivers or zest (Skillet-Seared Daikon with Yuzu, page 98). The midsection is perhaps the most versatile segment of the entire daikon. It can be seared, simmered, steamed, grated, shredded or thinly sliced and eaten raw or lightly pickled (Quick-Fix Pickles: Fruity, Sweet-and-Sour Daikon, page 196). The tip of the root is best when it is grated and used as a condiment or garnish with fried foods. One of my favorites is Crispy-Creamy Tōfu, Southern Barbarian Style (page 178), which would be a fine addition to our Daikon-Zukushi feast. Bruised or misshapen daikon roots are often shredded and dried (if you have a dehydrator, you can make your own shreds—any segment of the root, and peels, can be made into kiriboshi daikon—or you can buy shelf-stable bags of them at Asian grocery stores). For our Daikon-Zukushi menu, I suggest a sweet, spicy, and tart pickle (page 204) made from kiriboshi daikon (sun-dried radish shreds).

When planning a meal, you need not choose between kansha and washoku as menu-organizing principles: each complements and enhances the other. For those of you who have cooked from Washoku, rest assured that the Daikon-Zukushi meal I have just described meets the guidelines for balancing color, flavor, and preparation method: white (daikon and rice), black (sesame seeds mixed with the daikon leaves and the soy glaze), red (carrots in the soup and the stir-fry), yellow (pickles and yuzu zest), and green (leafy daikon tops); sweet (sugar in the soy-glazed daikon and in the pickling brine), sour (pickles), and salty (soy sauce and miso), with accents of spice (7-blend spice, red chile) and bitterness (yuzu zest); raw (grated condiment), simmered and seared (soy-glazed daikon wheels), fried (crispy-creamy tōfu), and steamed (rice).

Kansha—appreciating good food and the efforts of those who make it—can be experienced and practiced at any age. If you have an opportunity to cook with, or for, young children, I encourage you to try your hand at making nutritionally balanced, aesthetically appealing, kid-friendly boxed lunches-to-go. The lunch pictured on page 168 features soy-glazed tōfu burgers (page 169) that youngsters adore. These protein-packed sliders could be served on small buns, with the salad greens tucked inside, American-sandwich style. But in Japan, where seasonal sensitivity is an important part of menu planning, cherry blossomߝstudded rice (page 25) would be enjoyed instead, obentō style, while flower-viewing in the company of friends and family. Serving fresh fruit is a great way to provide nutritional balance to a lunch menu, though whole fruit can be messy to peel and eat. Sliced citrus typically bruises, and the juice oozes, but these wedges of jellied grapefruit (page 232) are easy to make, pack, and eat.

MEAL PLANNING

Japanese meals are organized around a core of three foods: rice (or noodles), soup (clear, miso enriched, or puréed), and pickles. Greater volume and complexity are usually achieved by adding small dishes to this trio to round out the menu. Classic meal planning follows guidelines associated with Japan’s native culinary culture, washoku. Such meals achieve culinary harmony by balancing colors, flavors, and preparation methods. Without having to stop and do cumbersome nutritional arithmetic, you are assured of getting essential vitamins and minerals in your daily diet when you choose colorful ingredients (red, green, yellow, black, and white) at every meal. Using different cooking techniques (simmering, searing, keeping raw, steaming, and frying) provides textural interest that contributes to a sense of satisfied fullness while actually consuming less food. Serving a range of flavors (sweet, sour, and salty, with accents of spice and bitterness) curbs food cravings that could lead to overeating.

I have arranged recipes into chapters that I hope will help you plan well-rounded menus. For those of you not yet used to balancing the nutritional requirements of a vegan diet, I suggest you first choose a rice or noodle dish (nearly all of them in this book include produce), and then add one dish from each of the following three chapters: Fresh from the Market, The Well-Stocked Pantry, and Mostly Soy. By including one dish that features fresh produce from the market or farm, another that relies on kambutsu (dried foods) from the pantry, and a third that contains significant quantities of plant-sourced protein (mostly tōfu in its many forms), you will have assembled a nutritionally balanced meal without complicated calculations. If you have chosen a substantial rice or noodle dish, then the other dishes can be sides or toppings to the rice or noodles. Your meal can be expanded by the addition of a soup, pickles (think of them as fully dressed “salads”), and dessert, each of which has its own collection of recipes in separate chapters.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

You do not need to convert to eating only Japanese food to practice kansha. Nor do you have to assemble your meals from Japanese foodstuffs alone. Many of the dishes in this book can be happily incorporated into—or adapted to—American, Mediterranean, northern European, or other Asian menus.

Some people elect not to consume any animal flesh, dairy products, or eggs for metabolic reasons. Food allergies and other health-compromising issues such as elevated cholesterol seem to head the list. Others might follow a vegetarian or vegan regimen as an ethical choice—their way of demonstrating respect for animal life. Still others have a concern for the ecology of the planet that compels them to eat plant-based foods exclusively.

If you are just embarking on a plant-based diet, or combining vegetarian dishes with small quantities of meat, dairy, eggs, fish, and poultry to feed yourself or others, you will find lots of dishes and menu suggestions in Kansha to help you transition to a primarily vegetarian diet. If you have already chosen a vegetarian lifestyle but are unfamiliar with Japanese food, you will discover exciting new dishes and ideas to expand and enliven your repertoire.

Dōzo, meshiagaré—Go ahead, eat up!

Kansha means “appreciation,” an expression evident in many aspects of Japanese society and daily living. In a culinary context, the word acknowledges both nature’s bounty and the efforts and ingenuity of people who transform that abundance into marvelous food. In the kitchen and at table, in the supermarket and out in the gardens, fields, and waterways, kansha encourages us to prepare nutritionally sound and aesthetically satisfying meals that also avoid waste, conserve energy, and sustain our natural resources.

A keen appreciation of food does not require anyone to choose a plant-based diet, but it is in keeping with such a mindset. Kansha is about abundance—of grains, legumes, roots, shoots, leafy plants (aquatic and terrestrial), shrubs, herbs, berries, seeds, tree fruits and nuts—not abstinence (doing without meat, fish, poultry, eggs, or dairy). It is about nourishing ourselves with what nature provides, cleverly and respectfully applying human technique and technology in the process.

Kansha as both a concept and a practice is well integrated into Japanese culinary tradition. Indeed, it is one of several aspects of washoku, the ancient and indigenous food culture of Japan. Based on the notion that balancing color, flavor, and method of food preparation enables optimal nutrition and aesthetic satisfaction at table, the principles of washoku guide home cooks and food professionals alike to culinary harmony. As with my book Washoku: Recipes from the Japanese Home Kitchen, I want this volume to both stimulate your intellect and satisfy your palate. And, as is true of washoku, I believe that kansha as a guiding principle in procuring, preparing, and partaking of food is universal in its appeal and application.

A HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE ON KANSHA

Buddhism, with its inherent respect for life that eschews consumption of animals, was first introduced to Japan by way of Korea in the sixth century. Among Japan’s varied food traditions, shōjin ryōri, most often translated as “Buddhist cuisine” or “temple cookery,” has become synonymous with vegetarian cooking. Indeed it is vegan, as no animal products are used. Shōjin ryōri became well established during the Kamakura period (1185ߝ1333), a tumultuous time in Japan’s history as feudal warlords vied for power. No doubt life was particularly perilous, and therefore seemed even more precious.

SHŌJIN RYŌRI The word shōjin means “earnest commitment.” Shōjin ryōri is not about dietary restrictions, but rather respect for nature’s bounty and for the diligence and ingenuity of those who procure it.

As you might expect, the earnest endeavor to prepare food shuns the use of shortcuts. The time and energy required to assemble a classic shōjin ryōri dish such as goma-dōfu, a creamy sesame pudding, is part of the reason it appears on temple vegetarian menus. It is undeniably delicious when prepared in the traditional time-consuming and physically exhausting manner, but there is a simpler way to make the pudding: using neri goma (toasted sesame paste), rather than parching, crushing, and grinding the seeds yourself in a suribachi (grooved mortar), a roughly two-hour workout guaranteed to tone your upper arms. In this book, I will be offering you both ways: the classic method for those who wish to experience appreciation through their own effort and labor, and the modern method for those pressed for time or with physical limitations—in which case, your appreciation can be focused on the ingenious efforts of others. Kansha, in this example, would be gratitude for artisanally produced pure toasted sesame paste.

ICHI MOTSU ZEN SHOKU The need to use food and energy resources as fully and effectively as possible led to many frugal culinary customs in Japan. The ecologically and nutritionally sound practice of ichi motsu zen shoku (one food, used entirely) encourages the use of all edible parts of plant foods: peels, roots, shoots, stems, seeds, and flowers. Throughout the book, I will be alerting you to opportunities for making fine food from the trimmed-away bits and pieces of produce that inevitably accumulate as you prepare a meal. You will soon discover that nothing goes to waste in the kansha kitchen.

KONDATÉ-ZUKUSHI Another longstanding Japanese culinary practice, kondaté-zukushi takes pleasure in making a meal from a single ingredient. This custom of using seasonally and regionally available foodstuffs developed in response to cyclical abundance amidst otherwise limited food resources. The well-established Japanese notion that a single ingredient, transformed in myriad ways, can become the highlight of a complete meal was the driving force behind the original (and flamboyant) Iron Chef television program.

Ancient approaches that remain applicable and meaningful to modern society, ichi motsu zen shoku and kondaté-zukushi will be evident throughout this book. At the conclusion of this introduction, in the section called Practicing Kansha, I will walk you through the preparation of Daikon-Zukushi, a menu celebrating the full glory of a plump, snowy white, green-tufted radish.

RECENT DEVELOPMENTS

Since the 1970s, a number of social and dietary movements operating globally have combined to increase awareness of the benefits of adopting a vegetarian lifestyle. The modern macrobiotic movement, born in Japan and well traveled worldwide, has helped rekindle an interest in the ancient notion of food as medicine.

In Japan in the past decade, a growing consciousness of the importance of passing on Japanese culinary culture to future generations, combined with other food-related concerns, evolved into a grassroots movement known as shokuiku. The word itself, a combination of the calligraphy for “food” and for “education,” was coined by a group of food journalists to describe wide-ranging goals. Those aspirations included defining (and encouraging the adoption of) healthful dietary practices, recognizing the need to monitor safety in food production and distribution, and the training of young people’s palates to appreciate food prepared without chemical additives. In 2005, the shokuiku movement was formally recognized by the Japanese government’s Cabinet Office (Naikakufu), which influences policy and legislation in several key agencies, including the Ministry of Health, Labor and Welfare (Kōseisho); the Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries (Nōrinsuisansho); and the Ministry of Education (Mombusho).

Current societal concerns with ecology (environmental pollution) and economics (pinched household budgets) have also led to a renewed interest in no-waste vegetarian cooking. In particular, a marketing concept known as LOHAS (Lifestyles of Health and Sustainability), which includes valuing organic farming over conventional methods, has become important in Japan’s contemporary food supply and distribution networks. Combined with the recent advent of the Slow Food movement and its respect for old-fashioned ways that encourage artisanal production, even urban dwellers have access to excellent processed foods that support a healthful, plant-focused diet.

The Japanese have also recently embraced induction heat (IH) cooking, a flameless way to prepare food in which heat is produced by magnetic fields. IH cooking is thought to be safer, less costly (after the initial investment for the special countertop cooker), and kinder to the environment. It does, however, place special requirements on cookware: the outer surface of pots, pans, and skillets must be ferrous—no glass, ceramic, aluminum, or copper, for example—and must come in direct, flat contact with the IH cooktop. But these requisites have not slowed the spread of this new cooking medium.

PUTTING THEORY INTO PRACTICE

My goal in writing Kansha is to empower you to create wholesome, nutritionally balanced, plant-based dishes, easily integrating preparation of these dishes into your busy and, most likely, urban daily routine.

Being able to consider the relative merits of one foodstuff or technique compared to another requires a comfortable familiarity with a wide range of products and kitchen skills. I will help you build that knowledge base, expanding your culinary horizons and repertoire by introducing you to an array of possibly unfamiliar foods and techniques that were developed in tandem with Japan’s vegetarian traditions. To help you become a practitioner-cook of kansha, I have included a detailed reference section, A Guide to the Kansha Kitchen, at the back of this book. It is divided into two parts, A Catalog of Tools and Techniques and A Catalog of Ingredients.

As a teacher of the Japanese culinary arts, I believe that the best recipes demonstrate how the culture as a whole approaches food preparation. My recipes will guide you to an understanding of why certain procedures are performed in the Japanese kitchen, then teach you when and how to do what needs to be done by advising you on timing, techniques, and relative proportion of ingredients to use. I will be encouraging you to adopt a mindful, considered approach to food preparation beginning with menu planning that eliminates unnecessary time and energy or superfluous foodstuffs.

PRACTICING KANSHA

Nothing goes to waste in the kansha kitchen. Putting this ideal into practice means fully using the food that nature provides, minimizing waste while maximizing eating pleasure.

Many fruits and vegetables come to market oddly shaped, slightly bruised, or a bit past prime, though still full of flavor and brimming with nutrients. What often ends up in the trash bin—seeds, fruit peels, vegetable trimmings, and misshapen or overripe produce—can be transformed into tasty side dishes. One approach is to mash, crush, grate, and/or blend the pulp of less-than-perfect produce to make soups, sauces, and aspics. Another approach is to finely shred or mince these usual castoffs, and make crispy fritters or crunchy pickles from them. You will find dozens of recipes throughout the book for using these usual kitchen scraps creatively, deliciously.

Packaged pantry goods such as soy sauce and miso do not spoil easily, though they do lose their aroma within a few weeks of opening. Refrigerating opened packages helps slow the loss, but after a month or so you’ll find such products lack verve. That’s when revitalizing them, changing them into flavor-enhancing condiments, makes sense. Having a jar of homemade vegan Seasoned Soy Concentrate (page 131) at the back of your refrigerator will be a boon on busy days, and Robust Miso (page 132) will perk up rice or dress up sticks of raw vegetables in a pinch. Once you get the hang of it, you will be surprised at how much you can do to reduce waste and improve flavor and nutrition. Think of the resulting dishes as a bonus for your resourcefulness.

One way to experience kansha in your own kitchen is to build an entire meal around a single vegetable, using it fully. Consider constructing a menu to celebrate a glorious daikon you find at your local farmers’ market. Title your meal Daikon-Zukushi: daikon in its entirety!

Different sections of daikon have different flavor and texture profiles. I suggest you use the leafy tops for making a confetti-like condiment to toss into cooked rice (Rice Tossed with Radish Greens, page 23). Then, divide the root portion into three segments: the neck (nearest the leafy tuft; this is often green), the midsection (usually bulbous and snowy white), and the tapered tip. Peel each segment and use the peels in various dishes, such as soup (Red and White Miso Soup, page 82) and a spicy sauté (Spicy Stir-Fry, page 122). Any leftover peels can be stored in a resealable bag and refrigerated for several days. To make a hearty main course, sear thick wheels of daikon from the neck portion in a skillet, glazing them lightly with a sweetened soy sauce before topping with citrus peel slivers or zest (Skillet-Seared Daikon with Yuzu, page 98). The midsection is perhaps the most versatile segment of the entire daikon. It can be seared, simmered, steamed, grated, shredded or thinly sliced and eaten raw or lightly pickled (Quick-Fix Pickles: Fruity, Sweet-and-Sour Daikon, page 196). The tip of the root is best when it is grated and used as a condiment or garnish with fried foods. One of my favorites is Crispy-Creamy Tōfu, Southern Barbarian Style (page 178), which would be a fine addition to our Daikon-Zukushi feast. Bruised or misshapen daikon roots are often shredded and dried (if you have a dehydrator, you can make your own shreds—any segment of the root, and peels, can be made into kiriboshi daikon—or you can buy shelf-stable bags of them at Asian grocery stores). For our Daikon-Zukushi menu, I suggest a sweet, spicy, and tart pickle (page 204) made from kiriboshi daikon (sun-dried radish shreds).

When planning a meal, you need not choose between kansha and washoku as menu-organizing principles: each complements and enhances the other. For those of you who have cooked from Washoku, rest assured that the Daikon-Zukushi meal I have just described meets the guidelines for balancing color, flavor, and preparation method: white (daikon and rice), black (sesame seeds mixed with the daikon leaves and the soy glaze), red (carrots in the soup and the stir-fry), yellow (pickles and yuzu zest), and green (leafy daikon tops); sweet (sugar in the soy-glazed daikon and in the pickling brine), sour (pickles), and salty (soy sauce and miso), with accents of spice (7-blend spice, red chile) and bitterness (yuzu zest); raw (grated condiment), simmered and seared (soy-glazed daikon wheels), fried (crispy-creamy tōfu), and steamed (rice).

Kansha—appreciating good food and the efforts of those who make it—can be experienced and practiced at any age. If you have an opportunity to cook with, or for, young children, I encourage you to try your hand at making nutritionally balanced, aesthetically appealing, kid-friendly boxed lunches-to-go. The lunch pictured on page 168 features soy-glazed tōfu burgers (page 169) that youngsters adore. These protein-packed sliders could be served on small buns, with the salad greens tucked inside, American-sandwich style. But in Japan, where seasonal sensitivity is an important part of menu planning, cherry blossomߝstudded rice (page 25) would be enjoyed instead, obentō style, while flower-viewing in the company of friends and family. Serving fresh fruit is a great way to provide nutritional balance to a lunch menu, though whole fruit can be messy to peel and eat. Sliced citrus typically bruises, and the juice oozes, but these wedges of jellied grapefruit (page 232) are easy to make, pack, and eat.

MEAL PLANNING

Japanese meals are organized around a core of three foods: rice (or noodles), soup (clear, miso enriched, or puréed), and pickles. Greater volume and complexity are usually achieved by adding small dishes to this trio to round out the menu. Classic meal planning follows guidelines associated with Japan’s native culinary culture, washoku. Such meals achieve culinary harmony by balancing colors, flavors, and preparation methods. Without having to stop and do cumbersome nutritional arithmetic, you are assured of getting essential vitamins and minerals in your daily diet when you choose colorful ingredients (red, green, yellow, black, and white) at every meal. Using different cooking techniques (simmering, searing, keeping raw, steaming, and frying) provides textural interest that contributes to a sense of satisfied fullness while actually consuming less food. Serving a range of flavors (sweet, sour, and salty, with accents of spice and bitterness) curbs food cravings that could lead to overeating.

I have arranged recipes into chapters that I hope will help you plan well-rounded menus. For those of you not yet used to balancing the nutritional requirements of a vegan diet, I suggest you first choose a rice or noodle dish (nearly all of them in this book include produce), and then add one dish from each of the following three chapters: Fresh from the Market, The Well-Stocked Pantry, and Mostly Soy. By including one dish that features fresh produce from the market or farm, another that relies on kambutsu (dried foods) from the pantry, and a third that contains significant quantities of plant-sourced protein (mostly tōfu in its many forms), you will have assembled a nutritionally balanced meal without complicated calculations. If you have chosen a substantial rice or noodle dish, then the other dishes can be sides or toppings to the rice or noodles. Your meal can be expanded by the addition of a soup, pickles (think of them as fully dressed “salads”), and dessert, each of which has its own collection of recipes in separate chapters.

SOME FINAL THOUGHTS

You do not need to convert to eating only Japanese food to practice kansha. Nor do you have to assemble your meals from Japanese foodstuffs alone. Many of the dishes in this book can be happily incorporated into—or adapted to—American, Mediterranean, northern European, or other Asian menus.

Some people elect not to consume any animal flesh, dairy products, or eggs for metabolic reasons. Food allergies and other health-compromising issues such as elevated cholesterol seem to head the list. Others might follow a vegetarian or vegan regimen as an ethical choice—their way of demonstrating respect for animal life. Still others have a concern for the ecology of the planet that compels them to eat plant-based foods exclusively.

If you are just embarking on a plant-based diet, or combining vegetarian dishes with small quantities of meat, dairy, eggs, fish, and poultry to feed yourself or others, you will find lots of dishes and menu suggestions in Kansha to help you transition to a primarily vegetarian diet. If you have already chosen a vegetarian lifestyle but are unfamiliar with Japanese food, you will discover exciting new dishes and ideas to expand and enliven your repertoire.

Dōzo, meshiagaré—Go ahead, eat up!

Recenzii

“The kansha lifestyle asks for us to slow down and be more deliberate, and to cultivate an awareness of our surroundings, the seasons and the nature of our own appetites. How refreshing and wise!”

—TheKitchn.com, 1/13/11

“The word "kansha" means "appreciation," and there's much to appreciate with Elizabeth Andoh's celebration of Japanese vegan and vegetarian traditions. Andoh, who was Gourmet magazine's Japan correspondent for more than three decades, offers more than 100 recipes, many of them complicated enough for experienced cooks looking for a good challenge.”

—Portland Oregonian, Best of 2010, 12/21/10

“Because any cookbook by Elizabeth Andoh deserves a long, thoughtful look. Her latest, Kansha, is an elegant spread of vegan and vegetarian Japanese dishes, as narrated in her characteristic cultural history discovery tone.”

—LA Weekly, Squid Ink blog, Top 10 Cookbook And Drink Gift Pairings, 12/14/10

“It’s great to open up a cookbook and absorb all the years and effort that an author puts into the publication. If you’re into Japanese, vegan, or vegetarian cooking, Elizabeth Andoh’s Kansha should be in your collection. She writes with humor and utmost care because she wants you to understand and appreciate Japanese food traditions. The recipe collection is full of insights that she accumulated during her decades in Japan. . . . Kansha captures the culinary distinctions and artful aspects of Japanese cuisine. The food tastes good too!”

—Andrea Nguyen, Viet World Kitchen, 2010 Cookbook Picks, 12/11/10

"Kansha brings the abundance of possibilities plant foods offer into focus without dwelling on the absence of others, a more delicate, embracing approach. I’ve come away from this book with the feeling that Kansha, both the book and the word, embody a spirit that moves more from the heart and less from the brain. Above all it expresses grace. I was thinking of grace as in gracefulness, but it could also mean grace as in a state of grace, of gratitude, of giving thanks. This approach to vegan and vegetarian food involves a deep and subtle shift away from how we might usually approach dietary limits and choices."

—DeborahMadison.com, 12/7/10

“The Japanese-food expert expands vegans’ repertoire while making tofu appealing to all.”

—The New York Times Book Review, Web Extra: 25 More Cookbooks, 12/3/10

“Kansha is a large, lavish book, beautifully packaged and packed with foolproof recipes. More than that, though, it is a detailed compendium of Japanese food culture, making it the perfect gift for anyone interested in cooking and eating, irrespective of whether or not they are vegetarian.”

—The Japan Times, 12/2/10

“What's the vegetable equivalent of butcher's nose-to-tail, the meatless version of everything-but-the-squeal? In her latest cookbook, Kansha, Elizabeth Andoh explores the concept ichi motsu zen shoku (one food, used entirely), a Japanese vegan philosophy that means using every last bit of vegetables from frond-to-root. . . . Kansha is both a book and a concept worth exploring.”

—GOOD.com, 12/1/10

"Andoh is one of the premier writers of Japanese cuisine and she explains the philosophy behind the thoughtful and considered food choices the Japanese make."

—FoxNews.com, The Fox Foodie: Sixteen Sweet Cookbooks, 11/30/10

"In a world of meatless Mondays, how does a sanctimonious foodie keep a leg up? Tokyo-based chef Elizabeth Andoh’s Kansha is a good place to start. Her recipes for creamy leek soup, sour soy-pickled ramps, and brown sugar ice are authentically Japanese and tasty enough for carnivores."

—DailyCandy, The Best New Fall Cookbooks, 11/12/10

"Because of the lack of books available on this topic, this will be much appreciated not only by vegetarians, vegans, and Japanese food enthusiasts but by any adventurous cook looking for a distinctive perspective on fresh, healthy food. Highly recommended, especially for vegetarians, vegans, and those interested in green living."

—Library Journal, STARRED REVIEW, 9/15/10

“Kansha is a beautiful collection of gentle, thrifty recipes, and a fascinating introduction to Japanese vegetarian cooking. Elizabeth Andoh writes with authority and an infectious love of Japan and its culinary traditions.”

—Fuchsia Dunlop, author of Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China

“What a fresh and deeply informative book. The recipes are beguiling, and at last I can make sense out of Japanese ingredients I’ve long found mystifying. But I especially love the sensibility of Kansha, an approach to life and to food that feels so right. By all means, don’t skip the introduction of this wonderful new book from Elizabeth Andoh.”

—Deborah Madison, author of Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone and Seasonal Fruit Desserts

“It is with deep appreciation and utmost joy that I welcome the arrival of Kansha. So much more than just a recipe compendium, this gorgeous work serves as an exquisite, thoroughly detailed, careful, and caring guide to the people, culture, and cuisine of Japan. Working through Elizabeth’s dishes, I felt lovingly guided and nurtured, expertly instructed, and, finally, deliciously nourished. Kansha is clearly the work of a lifetime of passionate study, and a wonderful gift for every cook and appreciator of Japanese cuisine. I am so very grateful for it.”

—Michael Romano, chef, author, and President of Culinary Development, Union Square Hospitality Group

“Andoh is at once lyrical and meticulous, taking the reader effortlessly from the profundities of Japanese culinary philosophy to practical and novel culinary techniques. Not just for vegans and vegetarians, Kansha is a veritable treasure trove for transforming even the humblest of vegetables into delicacies, and for exploring the full potential of rice, noodles, and tofu.”

—Rachel Laudan, food historian and author of The Food of Paradise: Exploring Hawaii’s Culinary Heritage

“I haven’t been so excited about a new cookbook in years. Andoh’s book, Kansha, has stirred me so—I cannot wait to get cooking. From premise to practice, Andoh’s personal lessons to the cook are engaging and valuable. Even people who have never been to Japan will relish the vegetable dishes and enjoy the stimulation, authority, and, above all, the array of Japanese dishes Kansha provides. For Japan hands like me, who’ve missed the pickles, sesame tofu, and soy skin delicacies, it is as though the teacher we’ve wanted is by our side, showing us we can make these foods from scratch ourselves, far from Japan. Kansha means appreciation, and Andoh has my undying gratitude.”

—Merry White, professor of food anthropology at Boston University

—TheKitchn.com, 1/13/11

“The word "kansha" means "appreciation," and there's much to appreciate with Elizabeth Andoh's celebration of Japanese vegan and vegetarian traditions. Andoh, who was Gourmet magazine's Japan correspondent for more than three decades, offers more than 100 recipes, many of them complicated enough for experienced cooks looking for a good challenge.”

—Portland Oregonian, Best of 2010, 12/21/10

“Because any cookbook by Elizabeth Andoh deserves a long, thoughtful look. Her latest, Kansha, is an elegant spread of vegan and vegetarian Japanese dishes, as narrated in her characteristic cultural history discovery tone.”

—LA Weekly, Squid Ink blog, Top 10 Cookbook And Drink Gift Pairings, 12/14/10

“It’s great to open up a cookbook and absorb all the years and effort that an author puts into the publication. If you’re into Japanese, vegan, or vegetarian cooking, Elizabeth Andoh’s Kansha should be in your collection. She writes with humor and utmost care because she wants you to understand and appreciate Japanese food traditions. The recipe collection is full of insights that she accumulated during her decades in Japan. . . . Kansha captures the culinary distinctions and artful aspects of Japanese cuisine. The food tastes good too!”

—Andrea Nguyen, Viet World Kitchen, 2010 Cookbook Picks, 12/11/10

"Kansha brings the abundance of possibilities plant foods offer into focus without dwelling on the absence of others, a more delicate, embracing approach. I’ve come away from this book with the feeling that Kansha, both the book and the word, embody a spirit that moves more from the heart and less from the brain. Above all it expresses grace. I was thinking of grace as in gracefulness, but it could also mean grace as in a state of grace, of gratitude, of giving thanks. This approach to vegan and vegetarian food involves a deep and subtle shift away from how we might usually approach dietary limits and choices."

—DeborahMadison.com, 12/7/10

“The Japanese-food expert expands vegans’ repertoire while making tofu appealing to all.”

—The New York Times Book Review, Web Extra: 25 More Cookbooks, 12/3/10

“Kansha is a large, lavish book, beautifully packaged and packed with foolproof recipes. More than that, though, it is a detailed compendium of Japanese food culture, making it the perfect gift for anyone interested in cooking and eating, irrespective of whether or not they are vegetarian.”

—The Japan Times, 12/2/10

“What's the vegetable equivalent of butcher's nose-to-tail, the meatless version of everything-but-the-squeal? In her latest cookbook, Kansha, Elizabeth Andoh explores the concept ichi motsu zen shoku (one food, used entirely), a Japanese vegan philosophy that means using every last bit of vegetables from frond-to-root. . . . Kansha is both a book and a concept worth exploring.”

—GOOD.com, 12/1/10

"Andoh is one of the premier writers of Japanese cuisine and she explains the philosophy behind the thoughtful and considered food choices the Japanese make."

—FoxNews.com, The Fox Foodie: Sixteen Sweet Cookbooks, 11/30/10

"In a world of meatless Mondays, how does a sanctimonious foodie keep a leg up? Tokyo-based chef Elizabeth Andoh’s Kansha is a good place to start. Her recipes for creamy leek soup, sour soy-pickled ramps, and brown sugar ice are authentically Japanese and tasty enough for carnivores."

—DailyCandy, The Best New Fall Cookbooks, 11/12/10

"Because of the lack of books available on this topic, this will be much appreciated not only by vegetarians, vegans, and Japanese food enthusiasts but by any adventurous cook looking for a distinctive perspective on fresh, healthy food. Highly recommended, especially for vegetarians, vegans, and those interested in green living."

—Library Journal, STARRED REVIEW, 9/15/10

“Kansha is a beautiful collection of gentle, thrifty recipes, and a fascinating introduction to Japanese vegetarian cooking. Elizabeth Andoh writes with authority and an infectious love of Japan and its culinary traditions.”

—Fuchsia Dunlop, author of Shark’s Fin and Sichuan Pepper: A Sweet-Sour Memoir of Eating in China

“What a fresh and deeply informative book. The recipes are beguiling, and at last I can make sense out of Japanese ingredients I’ve long found mystifying. But I especially love the sensibility of Kansha, an approach to life and to food that feels so right. By all means, don’t skip the introduction of this wonderful new book from Elizabeth Andoh.”

—Deborah Madison, author of Vegetarian Cooking for Everyone and Seasonal Fruit Desserts

“It is with deep appreciation and utmost joy that I welcome the arrival of Kansha. So much more than just a recipe compendium, this gorgeous work serves as an exquisite, thoroughly detailed, careful, and caring guide to the people, culture, and cuisine of Japan. Working through Elizabeth’s dishes, I felt lovingly guided and nurtured, expertly instructed, and, finally, deliciously nourished. Kansha is clearly the work of a lifetime of passionate study, and a wonderful gift for every cook and appreciator of Japanese cuisine. I am so very grateful for it.”

—Michael Romano, chef, author, and President of Culinary Development, Union Square Hospitality Group

“Andoh is at once lyrical and meticulous, taking the reader effortlessly from the profundities of Japanese culinary philosophy to practical and novel culinary techniques. Not just for vegans and vegetarians, Kansha is a veritable treasure trove for transforming even the humblest of vegetables into delicacies, and for exploring the full potential of rice, noodles, and tofu.”

—Rachel Laudan, food historian and author of The Food of Paradise: Exploring Hawaii’s Culinary Heritage

“I haven’t been so excited about a new cookbook in years. Andoh’s book, Kansha, has stirred me so—I cannot wait to get cooking. From premise to practice, Andoh’s personal lessons to the cook are engaging and valuable. Even people who have never been to Japan will relish the vegetable dishes and enjoy the stimulation, authority, and, above all, the array of Japanese dishes Kansha provides. For Japan hands like me, who’ve missed the pickles, sesame tofu, and soy skin delicacies, it is as though the teacher we’ve wanted is by our side, showing us we can make these foods from scratch ourselves, far from Japan. Kansha means appreciation, and Andoh has my undying gratitude.”

—Merry White, professor of food anthropology at Boston University

Cuprins

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS VI

INTRODUCTION 1

Rice 8

Noodles 50

Stocks and Soups 72

Fresh from the Market 90

The Well-Stocked Pantry 128

Mostly Soy 154

Tsukemono 190

Desserts 222

A GUIDE TO THE KANSHA KITCHEN 241

A CATALOG OF TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES 241

A CATALOG OF INGREDIENTS 253

INDEX 286

INTRODUCTION 1

Rice 8

Noodles 50

Stocks and Soups 72

Fresh from the Market 90

The Well-Stocked Pantry 128

Mostly Soy 154

Tsukemono 190

Desserts 222

A GUIDE TO THE KANSHA KITCHEN 241

A CATALOG OF TOOLS AND TECHNIQUES 241

A CATALOG OF INGREDIENTS 253

INDEX 286

Descriere

This first book to introduce Japanese vegetarian and vegan cooking to Western cooks is written by an authority on Japanese cuisine. With its range of elegant and satisfying recipes, "Kansha" will appeal to anyone with an interest in the food of Japan.

Premii

- Gourmand World Cookbook Awards (USA Only) Winner, 2010