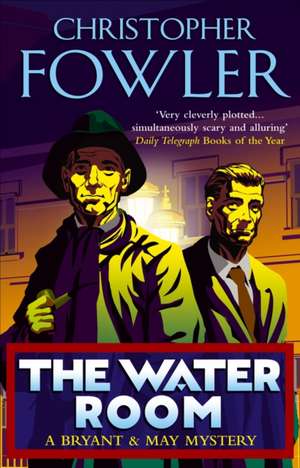

The Water Room: Bryant & May

Autor Christopher Fowleren Limba Engleză Paperback – sep 2005

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 59.61 lei 24-35 zile | +22.88 lei 4-10 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – sep 2005 | 59.61 lei 24-35 zile | +22.88 lei 4-10 zile |

| Bantam – 31 aug 2008 | 114.79 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 59.61 lei

Preț vechi: 70.42 lei

-15% Nou

Puncte Express: 89

Preț estimativ în valută:

11.41€ • 12.39$ • 9.58£

11.41€ • 12.39$ • 9.58£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-15 aprilie

Livrare express 15-21 martie pentru 32.87 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553815535

ISBN-10: 0553815539

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 129 x 204 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Seria Bryant & May

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0553815539

Pagini: 432

Dimensiuni: 129 x 204 x 32 mm

Greutate: 0.29 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Seria Bryant & May

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Christopher Fowler was the multiple award-winning author of almost fifty novels and short story collections, including the celebrated Bryant & May mysteries. His other novels include Roofworld, Spanky, The Sand Men and Hot Water. He has also written two acclaimed memoirs, Paperboy (winner of the Green Carnation Prize) and Film Freak, plus The Book of Forgotten Authors and Peculiar London, Bryant and May's singular and eccentric guide to the city. In 2015 Chris was awarded the Crime Writers Association's coveted 'Dagger in the Library' for his body of work. He lived in London and Barcelona. Diagnosed with cancer just as the UK went into lockdown in 2020, Chris died on 2nd March 2023.

Descriere

With the PCU facing an uncertain future, the death toll mounts and two of British fiction's most enigmatic detectives must face madness, greed and revenge, armed only with their wits, their own idiosyncratic practices and a plentiful supply of boiled sweets, in a wickedly sinuous mystery that goes to the heart of every London home.

Extras

Chapter One

A change in the weather

Arthur Bryant looked out over London and remembered.

Fierce sunlight swathed Tower Bridge beyond the rockeries of smouldering bomb-sites. A Thames sailing barge was arriving in the Pool of London with a cargo of palm kernels. Its dusty red sails sagged in the afternoon heat as it drifted past Broadway Dock at Limehouse, like a felucca on the Nile. Dairy horses trotted along the deserted Embankment, empty milk cans chiming behind them. Children swam from the wharves below St Paul’s, while carping mothers fanned away stale air from the river steps. He could smell horse dung and tobacco, meadow grass, the river. The world had once moved forward in single paces.

The vision wavered and vanished, displaced by sun-flares from the sealed glass corridors of the new city.

The old man in the unravelling sepia scarf waited for the rest of the party to gather around him. It was a Saturday afternoon at the start of October, and London’s thirteen-week heatwave was about to end with a vengeance. Already, the wind had changed direction, stippling the surface of the river with grey goose-pimples. Above the spire of St Paul’s, patulous white clouds deepened to a shade reminiscent of overwashed socks. The enervating swelter was giving way to a cool breeze, sharp in the shadows. The change had undermined his group’s stamina, reducing their numbers to a handful, although four polite but puzzled Japanese boys had joined thinking they were on the Jack the Ripper tour. Once everyone had settled, the elderly guide began the last section of his talk.

‘Ladies and gentlemen . . .’ He gave them the benefit of the doubt. ‘If you would care to gather a little closer.’ Arthur Bryant raised his voice as a red wall of buses rumbled past. ‘We are now standing on Blackfriars—formerly Pitt—Bridge.’ Remember to use the hands, he told himself. Keep their interest. ‘Bridges are causeways across great divides, in this case the rich city on the north side—’hand usage to indicate north—‘and the more impoverished south side. Does anyone have a Euro note in their pocket? Take it out and you’ll find a bridge, the universal symbol for something that unites and strengthens.’ He paused, less for effect than to catch his breath. Bryant really had no need to freelance as a city tour guide. His detective duties at the London Peculiar Crimes Unit would have kept a man half his age working late. But he enjoyed contact with the innocent public; most of the civilians he met in his day job were under criminal suspicion. Explaining the city to strangers calmed him down, even helped him to understand himself.

He pulled his ancient scarf tighter and abandoned his set text. What the hell, they were the last group of the season, and had proven pretty unresponsive. ‘According to Disraeli,’ he announced, ‘ “London is a nation, not a city.” “That great cesspool into which all the loungers of the Empire are irresistibly drained,” said Conan Doyle. “No duller spectacle on earth than London on a rainy Sunday afternoon,” according to De Quincey, so take your pick. One of the planet’s great crossing-points, it has more languages, religions and newspapers than any other place on earth. We divide into tribes according to age, wealth, class, race, religion, taste and personality, and this diversity breeds respect.’ Two members of the group nodded and repeated the word ‘diversity’, like an Oxford Street language class. God, this lot’s hard work, thought Bryant. I’m gasping for a cup of tea.

‘London’s main characteristic is an absence of form. Its thirty-three boroughs have busy districts running through them like veins, with no visible hierarchy, and neighbourhood ties remain inexplicably close. Because Londoners have a strongly pronounced sense of home, where you live counts more than who you are.’ Bryant mostly lived inside his head. Remember the facts, he told himself, they like facts.

‘We have six royal parks, 160 theatres, 8,600 restaurants, 300 museums and around 30,000 shops. Over 3,500 criminal offences are reported every day. Poverty and wealth exist side by side, often in the same street. Bombings caused slum clearance and social housing, rupturing centuries-old barriers of class, turning the concept into something mysterious and ever-shifting. London is truly unknowable.’

Bryant looked past his under-dressed audience to the swirling brown river. The Japanese boys were bored and cold, and had started taking pictures of litter bins. One of them was listening to music. ‘A city of cruelty and kindness, stupidity and excess, extremes and paradoxes,’ he told them, raising his voice. ‘Almost half of all journeys through the metropolis are made on foot. A city of glass, steel, water and flesh that no longer smells of beer and brick, but piss and engines.’

He lifted his silver-capped walking stick to the sky. ‘The arches of London’s Palladian architecture lift and curve in secular harmonies. Walls of glass reflect wet pavements in euphonious cascades of rain.’ He was no longer addressing the group, but voicing his thoughts. ‘We’re heading for winter, when a caul of sluggishness deepens into thanatomimesis, the state of being mistaken for death. But the city never dies; it just lies low. Its breath grows shallow in the cold river air while housebound tenants, flu-ridden and fractious with the perpetual motion of indoor activity, recover and grow strong once more. London and its people are parasites trapped in an ever-evolving symbiosis. At night the residents lose their carapace of gentility, bragging and brawling through the streets. The old London emerges, dancing drunk skeletons leaving graveyard suburbs to terrify the faint of heart.’

Now even the hardiest listeners looked confused. They spoke to each other in whispers and shook their heads. Their guide seemed to be straying from his topic: ‘A Historic Thameside Walk’. The Japanese boys gave up and wandered off. Someone said, rather loudly, ‘This tour was much better last time. There was a café.’

Bryant carried on, regardless.

‘London no longer suffers from the weight of its past. Now only the faintest resonance of legendary events remains. Oh, I can show you balustrades, pillars and scrollwork, point out sites of religious and political interest, streets that have witnessed great events, but to be honest there’s bugger all to see. It’s impossible to imagine the lives of those who came before us. Our visible history has been rubbed to a trace, like graffiti scrubbed from Portland stone. London has reinvented itself more completely than ever. And whoever grows up here becomes a part of its human history.’

He had completely lost his listeners. They were complaining to each other in dissatisfaction and disarray. ‘That concludes the tour for today,’ he added hastily. ‘I think we’ll skip question time, you’ve been a truly dreadful audience.’ He decided not to bother with his tip box as the mystified, grumbling group was forced to disperse across the windy bridge.

Bryant looked toward the jumble of outsized apartment buildings being constructed at the edge of the Thames, the yellow steel cranes clustered around them like praying mantises. After so many years in the service, he was quick to sense approaching change. Another wave of executives was colonizing the riverbank, creating a new underclass. He wondered how soon the invasion would provoke fresh forms of violence.

It’s metabolizing quickly, he thought. How long before it becomes unrecognizable? How can I hope to understand it for much longer?

He turned up his collar as he passed the urban surfers of the South Bank car park. The clatter of their skateboards bounced between the concrete arcades like the noise of shunting trains. Kids always found ways to occupy ignored spaces. He emerged into daylight and paced at the river rail, studying the evolving skyline of the Thames.

Hardly anything left of my childhood memories.

The Savoy, St Paul’s, the spire of St Bride’s, a few low monuments palisaded by international banks as anonymous as cigarette boxes. A city in an apostasy of everything but money. Even the river had altered. The ships and barges, no longer commercially viable, had left behind an aorta of bare brown water. Eventually only vast hotels, identical from Chicago to Bangkok, would remain.

As ever, Londoners had found ways of cutting grand new structures down to human size. The ‘Blade of Light’ connecting St Paul’s to Bankside had become known as ‘The Wobbly Bridge’. The Swiss Re building had been rechristened ‘The Erotic Gherkin’ long before its completion. Names were a sign of affection, to be worn like guild colours. The old marks of London, from its financial institutes to its market buildings, were fading from view like vanishing coats of arms.

I’ve been walking this route for over half a century, Bryant thought, stepping aside for a wave of shrieking children. A Mexican band was playing in the foyer of the Festival Hall. People were queueing for an art event involving tall multi-coloured flags. He remembered walking through the black empty streets after the War, and feeling completely alone. It was hard to feel alone here now. He missed the sensation.

His fingers closed around the keys in his pocket. Sergeant Longbright had mentioned she might go into the unit today in order to get things straight for Monday. He preferred to work out of hours, when the phonelines were closed and he could leave papers all over the floor without complaint. He could join Janice, collect his thoughts, smoke his pipe, prepare himself for a fresh start. For a woman who had recently retired, Longbright showed an alarming enthusiasm for returning.

For the past month, the Peculiar Crimes Unit—or rather, what was left of it—had been shunted into two sloping rooms above Sid Smith’s barbershop in Camden Town, while its old offices were being rebuilt. The relocation had been forced by a disastrous explosion that had destroyed the interior of the building and years of case files. The ensuing chaos had badly affected Bryant, whose office was virtually his home. He had lost his entire collection of rare books and artefacts in the blaze. Worse than that, he had yet to recover his dignity. The sheer embarrassment of being presumed dead! At least they had uncovered a long-dormant murderer, even if their methodology had proven highly abnormal.

But of course, nothing at the PCU had ever been normal. Founded as an experimental unit during the War to handle the cases no one else understood, let alone wanted, the detectives had built a reputation for defusing politically sensitive and socially embarrassing situations, using unorthodox and controversial methods. Some of the more rule-bound Met officers hated their guts, but most of the force’s foot soldiers regarded them as living legends, if only because they had repeatedly refused promotion to keep their status as ordinary detectives.

Bryant climbed the trash-stickered steps to Waterloo Bridge and hailed a taxi. Thirteen weeks of airless summer heat had passed without rain, but now the warmth was fading from the yellow London brick, and there was moisture in the rising breeze. The autumn chill stealing up the river would bring rheumatism and new strains of influenza. Already he could feel his joints starting to ache. The only thing that would take his mind off the problems of old age was hard work.

He dug into a pocket and found his pewter flask, granting himself a small nip of cherry brandy. When he was alone he thought too much. John May was the only person who could bring calm to his sense of escalating panic. Their fifty-year-plus partnership had the familiarity of an old radio show. The bald head gave a little shake within its yards of musty scarf; Bryant told himself he would never consider retiring again. The thought of doing so made him feel ill. When the unit reopened in its rightful office on Monday morning, he would return to his desk beside John and Janice, and stay in harness until the day he died. After all, it was where he was needed most. It would be important to show he could still do the job. And he had nothing else without it.

Chapter Two

The first death of autumn

‘I came to you, Mr Bryant,’ said Benjamin Singh, ‘because you have such an incredible capacity to be annoying.’

‘I can’t imagine what you mean,’ said Bryant, stuffing his bentwood pipe with a mixture of Old Holborn and eucalyptus leaves.

‘I mean you can get things done by badgering people. I don’t trust the regular police. They’re distracted and complacent. I’m glad you are still here. I thought you would have retired by now. You are so very, very far past retirement age.’

Bryant fixed his visitor with an evil eye. Mr Singh dabbed his cheeks with a paper handkerchief. He hadn’t been crying; it was a gesture of respect for the dead. He paused to take stock of his surroundings. ‘I’m sorry, have you been burgled?’ he asked.

‘Oh, no.’ Bryant fanned out his match and sucked noisily on the pipe. ‘The unit burned down. Well, it blew up and burned down. They’re still rebuilding it and we haven’t had time to unpack anything yet. We don’t officially reopen for business until ten o’clock this morning. It’s only nine, you know. It’ll be a nightmare around here later because we’ve got painters, carpenters and IT bods turning up. There’s no floor in the toilet. Health and Safety said they wouldn’t be responsible if we moved in, but we couldn’t stay above a barbershop. It doesn’t help that I’m also in the middle of moving house, and appear to have mislaid all my socks. Sorry, do please go on.’

‘Perhaps we should go and see Mr Singh’s sister,’ ventured Sergeant Longbright.

‘No one will move her body until I tell them to, Janice.’ Bryant shot her a look.

Longbright knew better than to argue with Arthur’s working methods. The inability of the Peculiar Crimes Unit to conduct its affairs in a conventional manner was embarrassingly well documented. Having abandoned attempts to make it properly accountable, the Home Office had now separated the unit from Metropolitan Police jurisdiction and placed it under the nebulous security services of MI7. There would be certain advantages: the detectives would no longer have to pay exorbitant charges for equipment usage or fight the Met for their annual budget, and the old demarcation lines would finally be resolved, but they would now be accountable to passing governments, where personal resentments ran deep. Bryant and his partner John May had been given six months to make the revised unit successful or train up their own replacements, for they were—as everyone seemed so keen to point out—both far beyond the statutory retirement age. There had been talk of closing the place down altogether, and yet it seemed a guardian angel existed in the labyrinth of Whitehall, because eleventh-hour reprieves continued to appear with the regularity of rainbows.

‘I didn’t have time to change.’ Benjamin Singh indicated his clothes, clearly feeling disrespectful for wearing a stripy tank-top, brown trousers and a purple shirt. ‘I visit my sister Ruth every Monday morning to clean the house for her,’ he explained. ‘She’s very old and can’t lift the vacuum cleaner. The moment I opened the front door, I knew something was wrong. She was sitting on a chair in the basement, dressed for the shops, which was strange because she knows I always go for her. Ruth just makes out the list. She was cold to the touch.’

‘Forgive me, but I don’t understand why you didn’t immediately call for an ambulance.’ Bryant remembered that the new office had a smoking ban, and tamped out his pipe before Longbright had a chance to complain.

‘She was dead, Arthur, not sick. Kentish Town police station is only three streets away from her house, so I walked around there and saw the duty sergeant, but I didn’t like his attitude— he told me to call an ambulance as well—so I came here.’

‘You know we don’t take cases off the street any more, Ben,’ Bryant explained. ‘They have to come to us through proper channels now.’

‘But when I found her, my first thought was to—’

‘You’re supposed to be recording this conversation, Arthur,’ Longbright interrupted. ‘From now on we have to stick to the rulebook.’

Bryant poked about in the cardboard box at his feet and pulled out a battered dictaphone. ‘Here,’ he offered, ‘you have a go. It doesn’t seem to let me record, for some reason. Perhaps I’m doing something wrong.’ The patented helpless look suggested innocence but didn’t wash with Longbright, who was familiar with her boss’s ability to cause malfunctions in the simplest equipment. Bryant was no longer allowed to touch the computers owing to the odd demagnetizing effect he had on delicate technology. His application to attend an IT course had been turned down six times by those who feared he would cause a national meltdown if let loose near PITO, the Police Information Technology Organization. His facility for picking up old broadcasts of Sunday Night at the London Palladium on his Sky dish had been documented with fascination but no hope of explanation by the Fortean Times.

‘All right, let’s go and have a look at your sister.’ Bryant clambered wearily to his feet. Tortoise-like, scarf-wrapped, argumentative to the point of rudeness, myopic and decrepit, Bryant appeared even more dishevelled than usual, owing to the current upheavals in his life. A waft of white hair rose in a horseshoe above his ears, as if he’d been touching static globes at the Science Museum. Behind his watery sapphire eyes, though, was a spirit as robust and spiky as winter earth. He had been described as ‘independent to the point of vexation and individual to the level of eccentricity’, which seemed accurate enough. John May, his dapper partner, was younger by three years, an attractive senior of considerable charisma, modern in outlook and gregarious by nature. Bryant was a loner, literate and secretive, with a sidelong, crafty mind that operated in opposition to May’s level-headed thinking.

‘Janice, when John finally deigns to turn up, would you send him around to join us? Where are we going?’

‘Number 5, Balaklava Street,’ said Mr Singh. ‘It’s between Inkerman Road and Alma Street.’

‘Ah, your sister’s house was built in the 1850s, then. The roads are all named after battles of the Crimean War. Victorian town councils were fond of such gestures.’ Bryant knew historical facts like that. It was a pity he couldn’t remember anything that had happened in the last twenty years. Recent events were his partner’s speciality. John May remembered everyone’s birthdays. Bryant barely recalled anyone’s names. May exhibited a natural charm that disarmed the toughest opponents. Bryant could make a nun bristle. May had girlfriends and relatives, parties and friends. Bryant had his work. May would smile in blossoming sunlight. Bryant would frown and step back into darkness. Each corresponding jag and trough in their characters was a further indication of the symbiosis they had developed over the years. They fitted together like old jigsaw pieces.

Longbright waited for Bryant to leave the office, then opened all the windows to clear the overpowering smell of paint. She set about unpacking the new computers, thankful that the old man could occupy his mind with the unit’s activities once more; he had been driving everyone mad for the past month, acting like a housebound child on a rainy day.

Arthur’s sudden decision to move house had been uncharacteristic. Furthermore, he had chosen to leave behind his landlady, the woman who had tolerated his dreadful behaviour for more than forty years. Alma Sorrowbridge had been shocked and hurt by her tenant’s determination to abandon her in Battersea as he moved alone to the workshop of a converted false-teeth factory in Chalk Farm. As she unbattened boxes and uncoiled cables, Longbright wondered at his motive. Perhaps Arthur felt that time was running short, and was preparing to distance himself from those closest to him. Perversely, his morbidity always increased when he was removed from death. Proximity to a fresh tragedy concentrated his mind wonderfully. Truly ghastly events took years off him.

Longbright caught herself humming as she worked, and realized that she was happy again.

‘So you and Mr May still have the Peculiar Crimes Unit.’ Mr Singh made conversation as he drove his little blue Nissan from Mornington Crescent to Kentish Town. Bryant had given the unit his Mini Cooper, a sixties relic with a history of rust and electrical faults, and as it was away being repaired he was forced to rely on getting lifts, which at least allowed the pedestrian population of north London to breathe a collective sigh of relief.

‘Yes, but we’ve had a change of brief since the days when you worked with us,’ said Bryant. ‘Now it’s problem homicides, low-profile investigations, cases with the potential to spark social panic, general unrest and malaise. We get the jobs that don’t lead anywhere and don’t suit Met’s wide-boys. They’re too busy number-crunching; the last thing they want is the kind of investigation that hangs around for months without producing quantifiable results. They have league tables now.’

‘So you’re meant to free up the regular police.’

‘I suppose that’s how they see it. We’ve had a few successes, but of course the cases that pay off are never the ones you expect.’ He wasn’t complaining. While everyone else was streamlining operations to board the law-enforcement superhighway, the PCU remained an unreliable but essential branch line no one dared to close down, and that was how he liked it. ‘I’m sorry you were the one who had to find your sister.’

‘It’s not her dying, you understand, I’ve been expecting that. But something is wrong, you’ll see.’

‘What are you doing these days?’

‘Both my daughters finally married. I said to them, “Don’t wed Indian boys, they’ll make you have babies instead of careers,” but they wouldn’t listen to me, so I fear there will be no more academics bearing my name. I retired from the British Library when it moved to King’s Cross, but I’m still lecturing on pagan cults.’ Benjamin had once provided the unit with information allowing them to locate a Cornish devil cult. ‘You know, I had asked Ruth to move in with me, but she was too independent. We never got on well with each other. I wanted her to wear one of those things around her neck, a beeper, you know? She refused. Now look where it’s got her.’ This time, Bryant noticed, Mr Singh’s tissue came away damp.

The little Nissan turned a corner and came to a stop.

Balaklava Street was a surprise. It was cobbled, for a start; few such thoroughfares had survived the most recent invasion of property developers, and only an EEC ruling had prevented London’s councils from ripping up the remaining streets. The pavement consisted of velvety flagstones, the kind that were pleasurable to roller-skate over, and ran in a dog-leg that provided the road with the appearance of a cul-de-sac. Commuters rarely used it as a rat-run and casual pedestrians were infrequent, so a peculiar calm had settled across the roof slates, and it was quiet in the way that London backstreets could often be, with the traffic fading to a distant hum and the rustling of high plane trees foregrounded by birdsong. Deep underground, passing Tube trains could be faintly detected, and only the proliferation of parked cars suggested modern times.

Bryant opened the car door and eased himself out with the help of the hated walking stick that May had bought for his last birthday. He noted that the framework of the street’s original gas lamps still stood, although they had been rewired for electric light. There were ten terraced yellow-brick houses, five on each side, before the road skirted a Victorian school that had been converted into an adult-education centre. Opposite, at the end of the road, a parched patch of waste ground was backed by the car park of a kitchen centre and a chaotic wood joinery, the triangle forming a dark corner where youths could play football by day and buy drugs at night.

At this end of the street, beyond the terraces, someone had dumped an old sofa, a dead television and some fractured chairs against a wall, creating an al fresco lounge. The walls of the school had been daubed with luxuriant graffiti and stencilled slander, marked with the initials IDST (‘If Destroyed, Still True’). Around the next corner was a van-repair centre, a hostel and a block of spacious loft apartments. Different worlds abutted without touching.

Mr Singh slipped a disability permit on to the dashboard. ‘I have to use this,’ he explained, ‘Camden has zoned all the streets and they’ll tow me away otherwise, the greedy cash-grabbing bastards. They’ve no respect for a decent educated man. What are their qualifications, I’d like to know?’

Bryant smiled to himself. Benjamin was still confusing culture and commerce, even though it was twenty years since they had last met. ‘Number 5, you say?’ He waved his stick at the littered front garden. Although it appeared relatively prosperous, the street had obviously seen better times. The houses had been amended with white porches, sills and railings, probably Edwardian additions, but these had started to corrode, and were not being replaced. Each house had two floors above the road, one floor below. It was starting to spit with rain, and the front steps looked slippery. At Bryant’s age, you noticed things like that.

Mr Singh had trouble with the keys. He seemed understandably nervous about going back into his sister’s house. Bryant could detect a sour trace of damp in the dark hall. ‘Don’t touch anything,’ he warned. ‘I shouldn’t really let you lead the way, but—well, we still do things differently at the PCU.’ He tried the lights, but nothing happened.

‘They disconnected Ruth after she refused to pay the bill,’ Mr Singh explained. ‘She was getting—I wouldn’t say crazy; difficult, perhaps. Of course, we were raised by oil-light, because our grandmother retained fond memories of her home in India. But the basement here is always dark, and the stairs can be treacherous. Wait, there are candles.’ He rattled a box and lit a pair.

Bryant saw Mr Singh’s point as they descended. ‘You found her down here?’ he asked.

‘This is the puzzle, as you will see.’ Mr Singh entered a shadowed doorway to the left of a small kitchen. The size of the bathroom took Bryant by surprise; it was disproportionately large, taking up more than half of the basement. The old lady was tiny, as dry and skeletal as a long-dead sparrow. She was seated on a large oak chair, her booted feet barely reaching the floor, her head tilted back on a single embroidered cushion draped over the top rail, her hands in her lap, touching with their palms up. The position looked comfortable enough, as though she had simply dropped back her head and died, but Bryant felt this was not a place where one would naturally choose to sit. There was no table or stool, nowhere to place a light, nor were there any proper windows to look out of. The chair was a piece of furniture on to which you would throw your clothes. Ruth Singh was dressed for going outside. She was even wearing a scarf.

‘You see, this is all wrong,’ said her brother, turning uncomfortably in the doorway. ‘It doesn’t seem at all natural to me. It’s not like her.’

‘Perhaps she came down to get something, felt a pain in her chest and sat down for a moment to regain her breath.’

‘Of course not. Ruth had absolutely nothing wrong with her heart.’

That’s why you came to see me, thought Bryant. You can’t accept that she might just have sat down and died. ‘You’d be surprised,’ he said gently. ‘People often pass away in such small, unready moments.’ He approached the old woman’s body and noted her swollen, livid ankles. Ruth Singh’s blood had already settled. She had been seated there for some hours, probably overnight. ‘Doesn’t seem to be any heat in here.’

‘It’s been hot for so long. There’s a storage heater for the winter. Oh dear.’

Bryant watched his old colleague. ‘Go to the back door and take a deep breath. I think it will be better if you wait outside while I take a quick look at her. It isn’t really my job, you know. I’ll only get told off for interfering.’

The room was cool enough to have slowed Mrs Singh’s body processes down. Bryant knew he would have to bring in Giles Kershaw, the unit’s new forensic officer, for an accurate time of death. The rug beneath the old woman’s boots looked wet.

‘There’s no one else left now, just us,’ murmured Mr Singh, reluctant to leave. ‘Ruth never married, she could have had her pick of the boys but she waited too long. She shamed her parents, being so English. All her life she was fussy and independent. My sister was a headstrong woman, my daughters are not. It seems the generations can no longer teach each other. Everything is out of place.’ He shook his head sadly, pulling the door shut behind him.

The room was so still. It felt as if even the dust in the air had ceased to circulate. Bryant drew a breath and gently exhaled, turning his head. Watery light filtered in from an opaque narrow window near the ceiling, at the pavement level of the bathroom. Perhaps it had opened once for ventilation, but layers of paint had sealed it shut.

Ruth Singh looked as if she could have died watching television, were it not for being in the wrong room, and for the odd position of her legs. She had not suffered a heart attack and simply sat down, because her hands were carefully folded in her lap. Something wasn’t right. Bryant absently stroked the base of his skull, leaving the nimbus of his white hair in tufted disorder. With a sigh, he removed a slim pack from his pocket and separated a pair of plastic anti-static gloves. He performed the obvious checks without thinking: observe, touch, palpate, listen. No cardiac movement, no femoral or carotid pulse, bilateral dilation in the clouded eyes. The skin of her arm did not blanch when he applied pressure; it was cold but not yet clammy. Setting the candle closer, he slipped his hand behind her neck and gently tried to raise her head. The stiffness in the body was noticeable, but not complete. At a rough guess she had been dead between eight and twelve hours, so she would have passed away between five-thirty pm and nine-thirty pm on Sunday night. Kershaw would be able to narrow it down.

When he tried to remove his hand, he was forced to raise the body, but the cushion slipped and Ruth rolled sideways. Next time I’ll leave this to a medic, he thought, trying to upright her, but before he had a chance to do so, she spat on him. Or rather, a significant quantity of water emptied from her mouth on to his overcoat.

Bryant wiped himself down, then gently prised her lips apart. Two gold teeth, no dental plate and a healthy tongue, but her throat appeared to be filled with a brownish liquid. As he moved his hand, it ran from the corner of her lower lip. He had assumed that the wetness of the rug had been caused by the incontinence of dying. Her clothes were dry. He checked on either side of the chair, then under it. There was no sign of a dropped glass, or any external water source. Passing to the bathroom cabinet, he found a toothbrush mug and placed it beneath her chin, collecting as much of the liquid as he could. He studied her mouth and nostrils for tell-tale marks left by fine pale foam, usually created by the mixture of water, air and mucus churned in a suffocating victim’s air passages. The wavering light made it hard to see clearly.

‘You’re going mad,’ he muttered to himself. ‘She dresses, she drowns, she sits down and dies, all in the comfort of her own home.’ He rose unsteadily to his feet, dreading the thought of having to warn Benjamin about a post-mortem.

Standing in the centre of the front room, he tried to see into Ruth Singh’s life. No conspicuous wealth, only simple comforts. A maroon Axminster rug, a cabinet of small brass ornaments, two lurid reproductions of Indian landscapes, some chintzy machine-coloured photographs of its imperial past, a bad Constable reproduction, a set of Wedgwood china that had never been used, pottery clowns, Princess Diana gift plates—a magpie collection of items from two cultures. Bryant vaguely recalled Benjamin telling him that his family had never been to India. Ruth Singh was two or three years older; perhaps she kept a trace-memory of her birth country alive through the pictures. It was important to feel settled at home. How had that comfort been disrupted? Not a violent death, he told himself, but an unnatural one, all the same.

From the Hardcover edition.

A change in the weather

Arthur Bryant looked out over London and remembered.

Fierce sunlight swathed Tower Bridge beyond the rockeries of smouldering bomb-sites. A Thames sailing barge was arriving in the Pool of London with a cargo of palm kernels. Its dusty red sails sagged in the afternoon heat as it drifted past Broadway Dock at Limehouse, like a felucca on the Nile. Dairy horses trotted along the deserted Embankment, empty milk cans chiming behind them. Children swam from the wharves below St Paul’s, while carping mothers fanned away stale air from the river steps. He could smell horse dung and tobacco, meadow grass, the river. The world had once moved forward in single paces.

The vision wavered and vanished, displaced by sun-flares from the sealed glass corridors of the new city.

The old man in the unravelling sepia scarf waited for the rest of the party to gather around him. It was a Saturday afternoon at the start of October, and London’s thirteen-week heatwave was about to end with a vengeance. Already, the wind had changed direction, stippling the surface of the river with grey goose-pimples. Above the spire of St Paul’s, patulous white clouds deepened to a shade reminiscent of overwashed socks. The enervating swelter was giving way to a cool breeze, sharp in the shadows. The change had undermined his group’s stamina, reducing their numbers to a handful, although four polite but puzzled Japanese boys had joined thinking they were on the Jack the Ripper tour. Once everyone had settled, the elderly guide began the last section of his talk.

‘Ladies and gentlemen . . .’ He gave them the benefit of the doubt. ‘If you would care to gather a little closer.’ Arthur Bryant raised his voice as a red wall of buses rumbled past. ‘We are now standing on Blackfriars—formerly Pitt—Bridge.’ Remember to use the hands, he told himself. Keep their interest. ‘Bridges are causeways across great divides, in this case the rich city on the north side—’hand usage to indicate north—‘and the more impoverished south side. Does anyone have a Euro note in their pocket? Take it out and you’ll find a bridge, the universal symbol for something that unites and strengthens.’ He paused, less for effect than to catch his breath. Bryant really had no need to freelance as a city tour guide. His detective duties at the London Peculiar Crimes Unit would have kept a man half his age working late. But he enjoyed contact with the innocent public; most of the civilians he met in his day job were under criminal suspicion. Explaining the city to strangers calmed him down, even helped him to understand himself.

He pulled his ancient scarf tighter and abandoned his set text. What the hell, they were the last group of the season, and had proven pretty unresponsive. ‘According to Disraeli,’ he announced, ‘ “London is a nation, not a city.” “That great cesspool into which all the loungers of the Empire are irresistibly drained,” said Conan Doyle. “No duller spectacle on earth than London on a rainy Sunday afternoon,” according to De Quincey, so take your pick. One of the planet’s great crossing-points, it has more languages, religions and newspapers than any other place on earth. We divide into tribes according to age, wealth, class, race, religion, taste and personality, and this diversity breeds respect.’ Two members of the group nodded and repeated the word ‘diversity’, like an Oxford Street language class. God, this lot’s hard work, thought Bryant. I’m gasping for a cup of tea.

‘London’s main characteristic is an absence of form. Its thirty-three boroughs have busy districts running through them like veins, with no visible hierarchy, and neighbourhood ties remain inexplicably close. Because Londoners have a strongly pronounced sense of home, where you live counts more than who you are.’ Bryant mostly lived inside his head. Remember the facts, he told himself, they like facts.

‘We have six royal parks, 160 theatres, 8,600 restaurants, 300 museums and around 30,000 shops. Over 3,500 criminal offences are reported every day. Poverty and wealth exist side by side, often in the same street. Bombings caused slum clearance and social housing, rupturing centuries-old barriers of class, turning the concept into something mysterious and ever-shifting. London is truly unknowable.’

Bryant looked past his under-dressed audience to the swirling brown river. The Japanese boys were bored and cold, and had started taking pictures of litter bins. One of them was listening to music. ‘A city of cruelty and kindness, stupidity and excess, extremes and paradoxes,’ he told them, raising his voice. ‘Almost half of all journeys through the metropolis are made on foot. A city of glass, steel, water and flesh that no longer smells of beer and brick, but piss and engines.’

He lifted his silver-capped walking stick to the sky. ‘The arches of London’s Palladian architecture lift and curve in secular harmonies. Walls of glass reflect wet pavements in euphonious cascades of rain.’ He was no longer addressing the group, but voicing his thoughts. ‘We’re heading for winter, when a caul of sluggishness deepens into thanatomimesis, the state of being mistaken for death. But the city never dies; it just lies low. Its breath grows shallow in the cold river air while housebound tenants, flu-ridden and fractious with the perpetual motion of indoor activity, recover and grow strong once more. London and its people are parasites trapped in an ever-evolving symbiosis. At night the residents lose their carapace of gentility, bragging and brawling through the streets. The old London emerges, dancing drunk skeletons leaving graveyard suburbs to terrify the faint of heart.’

Now even the hardiest listeners looked confused. They spoke to each other in whispers and shook their heads. Their guide seemed to be straying from his topic: ‘A Historic Thameside Walk’. The Japanese boys gave up and wandered off. Someone said, rather loudly, ‘This tour was much better last time. There was a café.’

Bryant carried on, regardless.

‘London no longer suffers from the weight of its past. Now only the faintest resonance of legendary events remains. Oh, I can show you balustrades, pillars and scrollwork, point out sites of religious and political interest, streets that have witnessed great events, but to be honest there’s bugger all to see. It’s impossible to imagine the lives of those who came before us. Our visible history has been rubbed to a trace, like graffiti scrubbed from Portland stone. London has reinvented itself more completely than ever. And whoever grows up here becomes a part of its human history.’

He had completely lost his listeners. They were complaining to each other in dissatisfaction and disarray. ‘That concludes the tour for today,’ he added hastily. ‘I think we’ll skip question time, you’ve been a truly dreadful audience.’ He decided not to bother with his tip box as the mystified, grumbling group was forced to disperse across the windy bridge.

Bryant looked toward the jumble of outsized apartment buildings being constructed at the edge of the Thames, the yellow steel cranes clustered around them like praying mantises. After so many years in the service, he was quick to sense approaching change. Another wave of executives was colonizing the riverbank, creating a new underclass. He wondered how soon the invasion would provoke fresh forms of violence.

It’s metabolizing quickly, he thought. How long before it becomes unrecognizable? How can I hope to understand it for much longer?

He turned up his collar as he passed the urban surfers of the South Bank car park. The clatter of their skateboards bounced between the concrete arcades like the noise of shunting trains. Kids always found ways to occupy ignored spaces. He emerged into daylight and paced at the river rail, studying the evolving skyline of the Thames.

Hardly anything left of my childhood memories.

The Savoy, St Paul’s, the spire of St Bride’s, a few low monuments palisaded by international banks as anonymous as cigarette boxes. A city in an apostasy of everything but money. Even the river had altered. The ships and barges, no longer commercially viable, had left behind an aorta of bare brown water. Eventually only vast hotels, identical from Chicago to Bangkok, would remain.

As ever, Londoners had found ways of cutting grand new structures down to human size. The ‘Blade of Light’ connecting St Paul’s to Bankside had become known as ‘The Wobbly Bridge’. The Swiss Re building had been rechristened ‘The Erotic Gherkin’ long before its completion. Names were a sign of affection, to be worn like guild colours. The old marks of London, from its financial institutes to its market buildings, were fading from view like vanishing coats of arms.

I’ve been walking this route for over half a century, Bryant thought, stepping aside for a wave of shrieking children. A Mexican band was playing in the foyer of the Festival Hall. People were queueing for an art event involving tall multi-coloured flags. He remembered walking through the black empty streets after the War, and feeling completely alone. It was hard to feel alone here now. He missed the sensation.

His fingers closed around the keys in his pocket. Sergeant Longbright had mentioned she might go into the unit today in order to get things straight for Monday. He preferred to work out of hours, when the phonelines were closed and he could leave papers all over the floor without complaint. He could join Janice, collect his thoughts, smoke his pipe, prepare himself for a fresh start. For a woman who had recently retired, Longbright showed an alarming enthusiasm for returning.

For the past month, the Peculiar Crimes Unit—or rather, what was left of it—had been shunted into two sloping rooms above Sid Smith’s barbershop in Camden Town, while its old offices were being rebuilt. The relocation had been forced by a disastrous explosion that had destroyed the interior of the building and years of case files. The ensuing chaos had badly affected Bryant, whose office was virtually his home. He had lost his entire collection of rare books and artefacts in the blaze. Worse than that, he had yet to recover his dignity. The sheer embarrassment of being presumed dead! At least they had uncovered a long-dormant murderer, even if their methodology had proven highly abnormal.

But of course, nothing at the PCU had ever been normal. Founded as an experimental unit during the War to handle the cases no one else understood, let alone wanted, the detectives had built a reputation for defusing politically sensitive and socially embarrassing situations, using unorthodox and controversial methods. Some of the more rule-bound Met officers hated their guts, but most of the force’s foot soldiers regarded them as living legends, if only because they had repeatedly refused promotion to keep their status as ordinary detectives.

Bryant climbed the trash-stickered steps to Waterloo Bridge and hailed a taxi. Thirteen weeks of airless summer heat had passed without rain, but now the warmth was fading from the yellow London brick, and there was moisture in the rising breeze. The autumn chill stealing up the river would bring rheumatism and new strains of influenza. Already he could feel his joints starting to ache. The only thing that would take his mind off the problems of old age was hard work.

He dug into a pocket and found his pewter flask, granting himself a small nip of cherry brandy. When he was alone he thought too much. John May was the only person who could bring calm to his sense of escalating panic. Their fifty-year-plus partnership had the familiarity of an old radio show. The bald head gave a little shake within its yards of musty scarf; Bryant told himself he would never consider retiring again. The thought of doing so made him feel ill. When the unit reopened in its rightful office on Monday morning, he would return to his desk beside John and Janice, and stay in harness until the day he died. After all, it was where he was needed most. It would be important to show he could still do the job. And he had nothing else without it.

Chapter Two

The first death of autumn

‘I came to you, Mr Bryant,’ said Benjamin Singh, ‘because you have such an incredible capacity to be annoying.’

‘I can’t imagine what you mean,’ said Bryant, stuffing his bentwood pipe with a mixture of Old Holborn and eucalyptus leaves.

‘I mean you can get things done by badgering people. I don’t trust the regular police. They’re distracted and complacent. I’m glad you are still here. I thought you would have retired by now. You are so very, very far past retirement age.’

Bryant fixed his visitor with an evil eye. Mr Singh dabbed his cheeks with a paper handkerchief. He hadn’t been crying; it was a gesture of respect for the dead. He paused to take stock of his surroundings. ‘I’m sorry, have you been burgled?’ he asked.

‘Oh, no.’ Bryant fanned out his match and sucked noisily on the pipe. ‘The unit burned down. Well, it blew up and burned down. They’re still rebuilding it and we haven’t had time to unpack anything yet. We don’t officially reopen for business until ten o’clock this morning. It’s only nine, you know. It’ll be a nightmare around here later because we’ve got painters, carpenters and IT bods turning up. There’s no floor in the toilet. Health and Safety said they wouldn’t be responsible if we moved in, but we couldn’t stay above a barbershop. It doesn’t help that I’m also in the middle of moving house, and appear to have mislaid all my socks. Sorry, do please go on.’

‘Perhaps we should go and see Mr Singh’s sister,’ ventured Sergeant Longbright.

‘No one will move her body until I tell them to, Janice.’ Bryant shot her a look.

Longbright knew better than to argue with Arthur’s working methods. The inability of the Peculiar Crimes Unit to conduct its affairs in a conventional manner was embarrassingly well documented. Having abandoned attempts to make it properly accountable, the Home Office had now separated the unit from Metropolitan Police jurisdiction and placed it under the nebulous security services of MI7. There would be certain advantages: the detectives would no longer have to pay exorbitant charges for equipment usage or fight the Met for their annual budget, and the old demarcation lines would finally be resolved, but they would now be accountable to passing governments, where personal resentments ran deep. Bryant and his partner John May had been given six months to make the revised unit successful or train up their own replacements, for they were—as everyone seemed so keen to point out—both far beyond the statutory retirement age. There had been talk of closing the place down altogether, and yet it seemed a guardian angel existed in the labyrinth of Whitehall, because eleventh-hour reprieves continued to appear with the regularity of rainbows.

‘I didn’t have time to change.’ Benjamin Singh indicated his clothes, clearly feeling disrespectful for wearing a stripy tank-top, brown trousers and a purple shirt. ‘I visit my sister Ruth every Monday morning to clean the house for her,’ he explained. ‘She’s very old and can’t lift the vacuum cleaner. The moment I opened the front door, I knew something was wrong. She was sitting on a chair in the basement, dressed for the shops, which was strange because she knows I always go for her. Ruth just makes out the list. She was cold to the touch.’

‘Forgive me, but I don’t understand why you didn’t immediately call for an ambulance.’ Bryant remembered that the new office had a smoking ban, and tamped out his pipe before Longbright had a chance to complain.

‘She was dead, Arthur, not sick. Kentish Town police station is only three streets away from her house, so I walked around there and saw the duty sergeant, but I didn’t like his attitude— he told me to call an ambulance as well—so I came here.’

‘You know we don’t take cases off the street any more, Ben,’ Bryant explained. ‘They have to come to us through proper channels now.’

‘But when I found her, my first thought was to—’

‘You’re supposed to be recording this conversation, Arthur,’ Longbright interrupted. ‘From now on we have to stick to the rulebook.’

Bryant poked about in the cardboard box at his feet and pulled out a battered dictaphone. ‘Here,’ he offered, ‘you have a go. It doesn’t seem to let me record, for some reason. Perhaps I’m doing something wrong.’ The patented helpless look suggested innocence but didn’t wash with Longbright, who was familiar with her boss’s ability to cause malfunctions in the simplest equipment. Bryant was no longer allowed to touch the computers owing to the odd demagnetizing effect he had on delicate technology. His application to attend an IT course had been turned down six times by those who feared he would cause a national meltdown if let loose near PITO, the Police Information Technology Organization. His facility for picking up old broadcasts of Sunday Night at the London Palladium on his Sky dish had been documented with fascination but no hope of explanation by the Fortean Times.

‘All right, let’s go and have a look at your sister.’ Bryant clambered wearily to his feet. Tortoise-like, scarf-wrapped, argumentative to the point of rudeness, myopic and decrepit, Bryant appeared even more dishevelled than usual, owing to the current upheavals in his life. A waft of white hair rose in a horseshoe above his ears, as if he’d been touching static globes at the Science Museum. Behind his watery sapphire eyes, though, was a spirit as robust and spiky as winter earth. He had been described as ‘independent to the point of vexation and individual to the level of eccentricity’, which seemed accurate enough. John May, his dapper partner, was younger by three years, an attractive senior of considerable charisma, modern in outlook and gregarious by nature. Bryant was a loner, literate and secretive, with a sidelong, crafty mind that operated in opposition to May’s level-headed thinking.

‘Janice, when John finally deigns to turn up, would you send him around to join us? Where are we going?’

‘Number 5, Balaklava Street,’ said Mr Singh. ‘It’s between Inkerman Road and Alma Street.’

‘Ah, your sister’s house was built in the 1850s, then. The roads are all named after battles of the Crimean War. Victorian town councils were fond of such gestures.’ Bryant knew historical facts like that. It was a pity he couldn’t remember anything that had happened in the last twenty years. Recent events were his partner’s speciality. John May remembered everyone’s birthdays. Bryant barely recalled anyone’s names. May exhibited a natural charm that disarmed the toughest opponents. Bryant could make a nun bristle. May had girlfriends and relatives, parties and friends. Bryant had his work. May would smile in blossoming sunlight. Bryant would frown and step back into darkness. Each corresponding jag and trough in their characters was a further indication of the symbiosis they had developed over the years. They fitted together like old jigsaw pieces.

Longbright waited for Bryant to leave the office, then opened all the windows to clear the overpowering smell of paint. She set about unpacking the new computers, thankful that the old man could occupy his mind with the unit’s activities once more; he had been driving everyone mad for the past month, acting like a housebound child on a rainy day.

Arthur’s sudden decision to move house had been uncharacteristic. Furthermore, he had chosen to leave behind his landlady, the woman who had tolerated his dreadful behaviour for more than forty years. Alma Sorrowbridge had been shocked and hurt by her tenant’s determination to abandon her in Battersea as he moved alone to the workshop of a converted false-teeth factory in Chalk Farm. As she unbattened boxes and uncoiled cables, Longbright wondered at his motive. Perhaps Arthur felt that time was running short, and was preparing to distance himself from those closest to him. Perversely, his morbidity always increased when he was removed from death. Proximity to a fresh tragedy concentrated his mind wonderfully. Truly ghastly events took years off him.

Longbright caught herself humming as she worked, and realized that she was happy again.

‘So you and Mr May still have the Peculiar Crimes Unit.’ Mr Singh made conversation as he drove his little blue Nissan from Mornington Crescent to Kentish Town. Bryant had given the unit his Mini Cooper, a sixties relic with a history of rust and electrical faults, and as it was away being repaired he was forced to rely on getting lifts, which at least allowed the pedestrian population of north London to breathe a collective sigh of relief.

‘Yes, but we’ve had a change of brief since the days when you worked with us,’ said Bryant. ‘Now it’s problem homicides, low-profile investigations, cases with the potential to spark social panic, general unrest and malaise. We get the jobs that don’t lead anywhere and don’t suit Met’s wide-boys. They’re too busy number-crunching; the last thing they want is the kind of investigation that hangs around for months without producing quantifiable results. They have league tables now.’

‘So you’re meant to free up the regular police.’

‘I suppose that’s how they see it. We’ve had a few successes, but of course the cases that pay off are never the ones you expect.’ He wasn’t complaining. While everyone else was streamlining operations to board the law-enforcement superhighway, the PCU remained an unreliable but essential branch line no one dared to close down, and that was how he liked it. ‘I’m sorry you were the one who had to find your sister.’

‘It’s not her dying, you understand, I’ve been expecting that. But something is wrong, you’ll see.’

‘What are you doing these days?’

‘Both my daughters finally married. I said to them, “Don’t wed Indian boys, they’ll make you have babies instead of careers,” but they wouldn’t listen to me, so I fear there will be no more academics bearing my name. I retired from the British Library when it moved to King’s Cross, but I’m still lecturing on pagan cults.’ Benjamin had once provided the unit with information allowing them to locate a Cornish devil cult. ‘You know, I had asked Ruth to move in with me, but she was too independent. We never got on well with each other. I wanted her to wear one of those things around her neck, a beeper, you know? She refused. Now look where it’s got her.’ This time, Bryant noticed, Mr Singh’s tissue came away damp.

The little Nissan turned a corner and came to a stop.

Balaklava Street was a surprise. It was cobbled, for a start; few such thoroughfares had survived the most recent invasion of property developers, and only an EEC ruling had prevented London’s councils from ripping up the remaining streets. The pavement consisted of velvety flagstones, the kind that were pleasurable to roller-skate over, and ran in a dog-leg that provided the road with the appearance of a cul-de-sac. Commuters rarely used it as a rat-run and casual pedestrians were infrequent, so a peculiar calm had settled across the roof slates, and it was quiet in the way that London backstreets could often be, with the traffic fading to a distant hum and the rustling of high plane trees foregrounded by birdsong. Deep underground, passing Tube trains could be faintly detected, and only the proliferation of parked cars suggested modern times.

Bryant opened the car door and eased himself out with the help of the hated walking stick that May had bought for his last birthday. He noted that the framework of the street’s original gas lamps still stood, although they had been rewired for electric light. There were ten terraced yellow-brick houses, five on each side, before the road skirted a Victorian school that had been converted into an adult-education centre. Opposite, at the end of the road, a parched patch of waste ground was backed by the car park of a kitchen centre and a chaotic wood joinery, the triangle forming a dark corner where youths could play football by day and buy drugs at night.

At this end of the street, beyond the terraces, someone had dumped an old sofa, a dead television and some fractured chairs against a wall, creating an al fresco lounge. The walls of the school had been daubed with luxuriant graffiti and stencilled slander, marked with the initials IDST (‘If Destroyed, Still True’). Around the next corner was a van-repair centre, a hostel and a block of spacious loft apartments. Different worlds abutted without touching.

Mr Singh slipped a disability permit on to the dashboard. ‘I have to use this,’ he explained, ‘Camden has zoned all the streets and they’ll tow me away otherwise, the greedy cash-grabbing bastards. They’ve no respect for a decent educated man. What are their qualifications, I’d like to know?’

Bryant smiled to himself. Benjamin was still confusing culture and commerce, even though it was twenty years since they had last met. ‘Number 5, you say?’ He waved his stick at the littered front garden. Although it appeared relatively prosperous, the street had obviously seen better times. The houses had been amended with white porches, sills and railings, probably Edwardian additions, but these had started to corrode, and were not being replaced. Each house had two floors above the road, one floor below. It was starting to spit with rain, and the front steps looked slippery. At Bryant’s age, you noticed things like that.

Mr Singh had trouble with the keys. He seemed understandably nervous about going back into his sister’s house. Bryant could detect a sour trace of damp in the dark hall. ‘Don’t touch anything,’ he warned. ‘I shouldn’t really let you lead the way, but—well, we still do things differently at the PCU.’ He tried the lights, but nothing happened.

‘They disconnected Ruth after she refused to pay the bill,’ Mr Singh explained. ‘She was getting—I wouldn’t say crazy; difficult, perhaps. Of course, we were raised by oil-light, because our grandmother retained fond memories of her home in India. But the basement here is always dark, and the stairs can be treacherous. Wait, there are candles.’ He rattled a box and lit a pair.

Bryant saw Mr Singh’s point as they descended. ‘You found her down here?’ he asked.

‘This is the puzzle, as you will see.’ Mr Singh entered a shadowed doorway to the left of a small kitchen. The size of the bathroom took Bryant by surprise; it was disproportionately large, taking up more than half of the basement. The old lady was tiny, as dry and skeletal as a long-dead sparrow. She was seated on a large oak chair, her booted feet barely reaching the floor, her head tilted back on a single embroidered cushion draped over the top rail, her hands in her lap, touching with their palms up. The position looked comfortable enough, as though she had simply dropped back her head and died, but Bryant felt this was not a place where one would naturally choose to sit. There was no table or stool, nowhere to place a light, nor were there any proper windows to look out of. The chair was a piece of furniture on to which you would throw your clothes. Ruth Singh was dressed for going outside. She was even wearing a scarf.

‘You see, this is all wrong,’ said her brother, turning uncomfortably in the doorway. ‘It doesn’t seem at all natural to me. It’s not like her.’

‘Perhaps she came down to get something, felt a pain in her chest and sat down for a moment to regain her breath.’

‘Of course not. Ruth had absolutely nothing wrong with her heart.’

That’s why you came to see me, thought Bryant. You can’t accept that she might just have sat down and died. ‘You’d be surprised,’ he said gently. ‘People often pass away in such small, unready moments.’ He approached the old woman’s body and noted her swollen, livid ankles. Ruth Singh’s blood had already settled. She had been seated there for some hours, probably overnight. ‘Doesn’t seem to be any heat in here.’

‘It’s been hot for so long. There’s a storage heater for the winter. Oh dear.’

Bryant watched his old colleague. ‘Go to the back door and take a deep breath. I think it will be better if you wait outside while I take a quick look at her. It isn’t really my job, you know. I’ll only get told off for interfering.’

The room was cool enough to have slowed Mrs Singh’s body processes down. Bryant knew he would have to bring in Giles Kershaw, the unit’s new forensic officer, for an accurate time of death. The rug beneath the old woman’s boots looked wet.

‘There’s no one else left now, just us,’ murmured Mr Singh, reluctant to leave. ‘Ruth never married, she could have had her pick of the boys but she waited too long. She shamed her parents, being so English. All her life she was fussy and independent. My sister was a headstrong woman, my daughters are not. It seems the generations can no longer teach each other. Everything is out of place.’ He shook his head sadly, pulling the door shut behind him.

The room was so still. It felt as if even the dust in the air had ceased to circulate. Bryant drew a breath and gently exhaled, turning his head. Watery light filtered in from an opaque narrow window near the ceiling, at the pavement level of the bathroom. Perhaps it had opened once for ventilation, but layers of paint had sealed it shut.

Ruth Singh looked as if she could have died watching television, were it not for being in the wrong room, and for the odd position of her legs. She had not suffered a heart attack and simply sat down, because her hands were carefully folded in her lap. Something wasn’t right. Bryant absently stroked the base of his skull, leaving the nimbus of his white hair in tufted disorder. With a sigh, he removed a slim pack from his pocket and separated a pair of plastic anti-static gloves. He performed the obvious checks without thinking: observe, touch, palpate, listen. No cardiac movement, no femoral or carotid pulse, bilateral dilation in the clouded eyes. The skin of her arm did not blanch when he applied pressure; it was cold but not yet clammy. Setting the candle closer, he slipped his hand behind her neck and gently tried to raise her head. The stiffness in the body was noticeable, but not complete. At a rough guess she had been dead between eight and twelve hours, so she would have passed away between five-thirty pm and nine-thirty pm on Sunday night. Kershaw would be able to narrow it down.

When he tried to remove his hand, he was forced to raise the body, but the cushion slipped and Ruth rolled sideways. Next time I’ll leave this to a medic, he thought, trying to upright her, but before he had a chance to do so, she spat on him. Or rather, a significant quantity of water emptied from her mouth on to his overcoat.

Bryant wiped himself down, then gently prised her lips apart. Two gold teeth, no dental plate and a healthy tongue, but her throat appeared to be filled with a brownish liquid. As he moved his hand, it ran from the corner of her lower lip. He had assumed that the wetness of the rug had been caused by the incontinence of dying. Her clothes were dry. He checked on either side of the chair, then under it. There was no sign of a dropped glass, or any external water source. Passing to the bathroom cabinet, he found a toothbrush mug and placed it beneath her chin, collecting as much of the liquid as he could. He studied her mouth and nostrils for tell-tale marks left by fine pale foam, usually created by the mixture of water, air and mucus churned in a suffocating victim’s air passages. The wavering light made it hard to see clearly.

‘You’re going mad,’ he muttered to himself. ‘She dresses, she drowns, she sits down and dies, all in the comfort of her own home.’ He rose unsteadily to his feet, dreading the thought of having to warn Benjamin about a post-mortem.

Standing in the centre of the front room, he tried to see into Ruth Singh’s life. No conspicuous wealth, only simple comforts. A maroon Axminster rug, a cabinet of small brass ornaments, two lurid reproductions of Indian landscapes, some chintzy machine-coloured photographs of its imperial past, a bad Constable reproduction, a set of Wedgwood china that had never been used, pottery clowns, Princess Diana gift plates—a magpie collection of items from two cultures. Bryant vaguely recalled Benjamin telling him that his family had never been to India. Ruth Singh was two or three years older; perhaps she kept a trace-memory of her birth country alive through the pictures. It was important to feel settled at home. How had that comfort been disrupted? Not a violent death, he told himself, but an unnatural one, all the same.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“They’re old, they’re cranky, and their chaotic work habits inevitably lead to disaster. But life always seems livelier whenever Arthur Bryant and John May are on a case!...An imaginative funhouse of a world where sage minds go to expand their vistas and sharpen their wits.” —New York Times Book Review

"Traditional mystery buffs with a taste for the offbeat will relish British author Fowler's wonderful second contemporary whodunit featuring the Peculiar Crimes Unit and its elderly odd couple, Arthur Bryant and John May."—Publishers Weekly, starred review

"A clever twist on the traditional police procedural... The real thrill here is the delightful duo in the starring roles, two fresh and unusual characters who manage to breathe new life into an established genre in which it’s getting harder and harder to find anything genuinely fresh."—Booklist

"Humorous, engaging."—Kirkus Reviews

“Entertaining and thrilling.” —Chicago Tribune

“More down to earth than [Jasper] Fforde but just as delightfully quirky.” —Seattle Times

"Traditional mystery buffs with a taste for the offbeat will relish British author Fowler's wonderful second contemporary whodunit featuring the Peculiar Crimes Unit and its elderly odd couple, Arthur Bryant and John May."—Publishers Weekly, starred review

"A clever twist on the traditional police procedural... The real thrill here is the delightful duo in the starring roles, two fresh and unusual characters who manage to breathe new life into an established genre in which it’s getting harder and harder to find anything genuinely fresh."—Booklist

"Humorous, engaging."—Kirkus Reviews

“Entertaining and thrilling.” —Chicago Tribune

“More down to earth than [Jasper] Fforde but just as delightfully quirky.” —Seattle Times