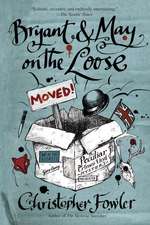

White Corridor: Bryant & May

Autor Christopher Fowleren Limba Engleză Paperback – 14 iul 2008

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 53.83 lei 26-32 zile | +26.30 lei 10-14 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 14 iul 2008 | 53.83 lei 26-32 zile | +26.30 lei 10-14 zile |

| Bantam – 31 aug 2008 | 114.19 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 53.83 lei

Preț vechi: 69.92 lei

-23% Nou

Puncte Express: 81

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.30€ • 10.78$ • 8.52£

10.30€ • 10.78$ • 8.52£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 20-26 martie

Livrare express 04-08 martie pentru 36.29 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780553817980

ISBN-10: 0553817981

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 128 x 197 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Seria Bryant & May

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0553817981

Pagini: 368

Dimensiuni: 128 x 197 x 27 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Transworld Publishers Ltd

Seria Bryant & May

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Christopher Fowler was the multiple award-winning author of almost fifty novels and short story collections, including the celebrated Bryant & May mysteries. His other novels include Roofworld, Spanky, The Sand Men and Hot Water. He has also written two acclaimed memoirs, Paperboy (winner of the Green Carnation Prize) and Film Freak, plus The Book of Forgotten Authors and Peculiar London, Bryant and May's singular and eccentric guide to the city. In 2015 Chris won the CWA's coveted 'Dagger in the Library' for his body of work. He lived in London and Barcelona. Diagnosed with cancer just as the UK went into lockdown in 2020, Chris died on 2nd March 2023.

Extras

Chapter One

Second Heart

"Concentrate on the moth."

The creature fluttered against the inside of the upended water glass as the women leaned in to watch. It was trying to reach the light from the amber street lamp that shone through the gap in the curtains. Each time its wings batted against its prison, the Shaded Broad-bar Scotopteryx chenopodiata shed more of the powder that kept it in flight, leaving arrow-imprints on the glass.

"Concentrate hard on the moth, Madeline."

In the early evening drizzle, the Edwardian terraced house at 24 Cranmere Road was like a thousand others in the surrounding South London streets, its quiddity to be a part of the city's chaotic whole. There were shiny grey slates, dead chimney pots and shabby bay windows. The rain sketched silver signatures across the rooftops, leaving inky pools on empty pavements. At this time of the year it was an indoor world.

Behind dense green curtains, five women sat in what had once been the front parlour, narrowing their thoughts in the overheated air. The house was owned by Kate Summerton, a prematurely grey housewife who had reached the age at which so many suburban women faded from the view of men. As if to aid this new invisibility, she tied back her hair and wore TV-screen glasses with catalogue slacks and a shapeless faun cardigan.

Her guests were all neighbours except Madeline Gilby, who worked in the Costcutter supermarket on the Old Kent Road and was disturbingly beautiful, even when she arrived still wearing her blue cashier's smock. Kate had known her for almost three years, and it had taken that long to convince her that she possessed a rare gift beyond that of her grace.

The small brown moth batted feebly once more, then sank to the tablecloth. It was losing strength. Madeline furrowed her brow and pressed pale hands to her temples, shutting her eyes tight.

"He's tiring. Keep concentrating."

The Broad-bar made one final attempt to escape through the top of the glass, and fell back. One wing ticked rapidly and then became still.

"That,"said Jessica, adjusting her great glasses, "shows the true intensity of the directed mind. The energy you generated is not measurable by any electronic means, and yet it's enough to interfere with the nervous system of this poor little creature. Of course, the test is hardly very scientific, but it suffices to demonstrate the power you hold within you."

Madeline was astonished. She gasped and smiled at the others.

"You have the gift, dear, as all women do in different degrees," said Kate. "In time, and with our help, you'll be able to identify the auras of others, seeing deep inside their hearts. You'll instinctively know if they mean you good or harm, and will never need to fear a man again. From now on, you and your son will be safe."

Kate was clear and confident, conscious of her middle-class enunciation. As a professional, she was used to being heard and obeyed. She turned to the others. "You see how easy it is to harness your inner self? It is important to understand that, in a manner of speaking, all women have two hearts. The first is the muscle that pumps our blood, and the second is a psychic heart that, if properly developed, opens us to secret knowledge. You can all harness that heart-power, just as Madeline is doing. Males don't possess this second spiritual heart; they have only flesh and bone. They feel pain and pleasure, but there is no extra dimension to their feelings, whereas we are able to find deeper shading in our emotional spirituality. This is the defence we develop against those who hurt us and our children, because most men do eventually, even if they never intend to. They are fundamentally different creatures, and fail to understand the damage they cause. With training, we can open a pathway illuminated by the pure light of truth, and see into the hearts of men. This is the breakthrough that Madeline has achieved today, in this room.?"

Madeline was unable to stop herself from crying. As a child she had been lonely and imaginative, used to spending long afternoons with books and make-believe friends until boys discovered her nascent beauty. Then the nightmare had begun. Now, there was a chance that it might really be over. For the first time since she had met Kate, she truly believed that her power existed.

"That's it, let it all out,"said her mentor, placing a plump arm around her as the others murmured their approval. "It always comes as a shock the first time. You'll get used to it."

Madeline needed air. She left the suffocating parlour and passed quickly through the herb-filled kitchen into the garden, where she found her son kicking sulkily at the flower beds that held etiolated rosebushes, each with a single despondent pink bloom.

"It's cold out here, Ryan. You should stay indoors."

"Her husband smokes."

"Even so." Madeline rubbed her bare arms briskly, looking about. The Anderson shelters and chicken sheds of postwar London had been replaced with rows of flat-pack conservatories. New attics and kitchens thrust out along the terrace, the residents pushing their property boundaries as if halfheartedly trying to break free of the past. "I'm ready to go now. Come and get your jacket. We'll go home."

As the neighbours gathered in the hall with their coats, Mrs Summerton removed the tumbler from the parlour table, crushing the moth between her thumb and forefinger before it had a chance to revive, flicking it into the waste bin. She had started her refuge over twenty years ago, when alcohol abuse had been the main problem. Now it was drugs, not that men needed to take stimulants before battering their partners. Madeline had come to her with a black eye and a sprained arm, but had still been anxious to get home on that first evening in order to cook her husband's dinner. Seeing the gratitude in her protegee's eyes made Kate sure she was doing the right thing, even if it meant performing a little parlour trick with a moth. Madeline was a good mother, kind and decent, but badly damaged by her relationships with men. If she could not be taught to seek independence and protect herself by traditional means, it was valid to introduce more unconventional methods. Mrs Summerton said her good-byes and closed the front door, then checked the time and went to change, remembering that someone new was coming to the shelter tonight. She only had room for eight women, and the new girl would make nine, but how would she ever forgive herself if she sent her home without help? Besides, the new girl came from a wealthy family; her fee could finance the refuge for months.

Mr Summerton stayed in the kitchen reading his paper. He had coped with the house being turned into a women's shelter, had even enjoyed it for a while, but now it was best to stay out of the way. His wife was honest down to her bones, he had always known that. She had made a few missteps in her overeagerness to help, that was all, but now she was exploring strange new territory, enjoining the women to discover their innate psychic powers and leave their husbands—encouraging suspicion and hatred of all men, of which he disapproved.

Still, she was a force of nature when she made up her mind, and he knew better than to raise his voice in protest. There had always been too many women in the house, Kate's friends, their daughters—even the cat was a female. His mother had once warned him that all women go mad eventually, and he was starting to believe it. Overlooked and outnumbered, he sipped his tea and turned to the sports pages.

Madeline walked home in the rain, clutching Ryan's hand too tightly. "Why are we walking?" asked the boy. "It's bloody freezing."

"Don't swear," his mother admonished. "I haven't got enough bus fare. It's not very far, and the exercise is good for you.?"

"That's because you gave all your money to her."

It was true that Mrs Summerton charged for her services, but you couldn't expect her to do it for nothing. Kate had made sense of her life. During her lonely childhood years, Madeline had been sure that some secret part of her was waiting to be discovered. But instead of gaining self-knowledge she became beautiful, and the curse began. Boys from her school hung around her house, laying their traps and baiting their lies with promises. She had even seen that terrible crafty gleam in her own father's eyes. She trusted easily, and was hurt each time. Beauty made her shy, and shyness made her controllable.

Now, at thirty years of age, she was finally discovering a way of standing up to the men who had always manipulated her. She owed Kate Summerton everything.

"Is she a lady doctor?"asked Ryan.

"Not exactly. What makes you think that?

"You went to see her when you hurt yourself."

Madeline had told her son that she'd fallen in the garden, and he seemed to believe her. "She was very kind to me," she said.

"You were ages in there," Ryan probed, watching her face in puzzlement. "I was stuck in the smoky kitchen with her horrible daughters and her boring husband. What were you doing?"

"Mrs Summerton was helping to teach me something."She was unsure about broaching the subject with her son. He was at the age where he seemed simultaneously too clever and too childish.

"You mean like school lessons?" Ryan persisted. 'What was she teaching you?'

Madeline remained quiet until they had turned the high corner wall of Greenwich Park. Winter mist was settling across the plane trees in a veil of dewdrops. "She was showing me how to deal with your father,?" she said at last.

Chapter Two

The Shaping of Men

Johann Bellocq stretched up on the staircase to the sea, and pulled another of the ripe orange loquats from the overhanging branches of the tree. Biting into them was like biting flesh. The juice ran down his chin, staining his blue nylon shirt, dripping darkly onto the hot steps. His stolen bounty held the sweet taste of sin. He spat the large stone at the landing below, watching it skitter and bounce into the storm drain, then loaded his pockets with all the sticky fruit he could touch on tiptoe. He was a tall, slim boy, and could reach into the dusty leaves for the most tender crops hidden from the flies and the harsh glare of the sun.

Summer had come early to la petite Afrique that year, encouraging his mother to keep the shutters closed, not that she needed much persuasion. She rarely allowed sunlight into the villa, so the rooms remained cold and damp-smelling deep into summer. Even when the mistral came, drawing dry northeasterly winds across the hills, she would not air the house. Thick yellow dust silted beneath the doors and across the window ledges, but she stubbornly refused to unseal the rooms. To allow nature in was to admit pagan forces, a blasphemous act of elemental obeisance that would disturb the pious sanctity of her home and unleash the powers of godlessness upon the three of them.

His mother was entirely mad.

Johann skipped up the steep staircase, noting the lowness of the sun in the cliffs above. He had no watch, but knew instinctively that his mother would be waiting to cruelly punish him. Today, though, he did not care.

He had just passed his twelfth birthday and was growing fast, already handsome, with a maturity beyond his age. Soon his grandfather would die, and he would be bigger than she. He could afford to bide his time.

He had stolen a transistor radio from one of the girls on the beach, and tuned it to a station that only played songs by the old French singers: Michel Delpech, Mireille Mathieu and Johnny Hallyday. He hated English bands, despised Culture Club and Queen, the arrogant regardez-moi prancing and posturing. He'd hidden the radio in the exhausted little orchard behind the house, where his mother would never find it. Pop was the Devil's music, and led to licentiousness, which was an old-fashioned word meaning sex. She would allow nothing in their home that might run the risk of destroying his innocence, because when boys discovered sex it turned their heads from God.

His stroke-afflicted grandfather, who lived with them, had ceased voicing his opinions, and spent his days drifting in dreams. Marcel's wife was dead, and he was not far behind. She had suffered cruelly with stomach cancer. If God was so merciful, why would he take two years to destroy a woman who had visited the little village church three times every Sunday and never uttered an unkind word in her life? Doubtless the old man would have liked to have asked his daughter this question, but knew all too well what she would say: God had tested her faith and found it wanting.

The house was tucked beneath umbrella pines and surrounded by twisted pale olive trees, their tortured roots thrust above the dry ground like ancient knees. Here the plants seeped pungent oils as a protection from the heat, as well as sharp-scented nectars that formed the bases for the area's perfume factories. No wooded aromas permeated the house, however. Perfume was the smell of sin, and was worn by the painted whores who paraded along the Avenue de la Californie after dark. His mother washed the edges of the doors and windows with disinfectant to keep the smell from entering.

Inside the little single-floored house, all was bare and white and pious. The rooms were scoured with bleach, the floors and steps with cleaning alcohol, the windows with paper and vinegar. In every room was a large pine crucifix, no other adornment. In the kitchen, a wooden table and three chairs, in the bedrooms iron bedsteads, narrow and rickety, topped with dented copper knobs, and above each bolster, a lurid picture of Our Lady, beatific and tortured, eyes rolled to Heaven. In his room, his mother had placed a faded Victorian sampler on the dresser, picked out in brown and white. Its stitched letters were a warning: "Dieu Voit Tout." God sees everything.

He hated the house, and longed to burn it to the ground. Soon the fierce cyanic blue of the Alpine skies would turn to grey, and winter would settle across the region, sealing them away from the world until spring. He would be left at the mercy of his mother. During the rare times when his grandfather was awake he protected the boy, but he was sleeping more and more, and could no longer be relied upon as a guardian.

Once, when Johann was seven years old, they had taken a holiday at Lac de l'Ascension, and his mother had pointed up into the dark sky, where rolling clouds had parted to release a shaft of sunlight down to the surface of the lake. "That," she told him, "is the pathway which leads directly to God. It is His way of watching all life on earth. He looks for those who flagrantly commit sin beneath His gaze, and punishes them."

"How does he do that, Mother?" asked Johann.

From the Hardcover edition.

Second Heart

"Concentrate on the moth."

The creature fluttered against the inside of the upended water glass as the women leaned in to watch. It was trying to reach the light from the amber street lamp that shone through the gap in the curtains. Each time its wings batted against its prison, the Shaded Broad-bar Scotopteryx chenopodiata shed more of the powder that kept it in flight, leaving arrow-imprints on the glass.

"Concentrate hard on the moth, Madeline."

In the early evening drizzle, the Edwardian terraced house at 24 Cranmere Road was like a thousand others in the surrounding South London streets, its quiddity to be a part of the city's chaotic whole. There were shiny grey slates, dead chimney pots and shabby bay windows. The rain sketched silver signatures across the rooftops, leaving inky pools on empty pavements. At this time of the year it was an indoor world.

Behind dense green curtains, five women sat in what had once been the front parlour, narrowing their thoughts in the overheated air. The house was owned by Kate Summerton, a prematurely grey housewife who had reached the age at which so many suburban women faded from the view of men. As if to aid this new invisibility, she tied back her hair and wore TV-screen glasses with catalogue slacks and a shapeless faun cardigan.

Her guests were all neighbours except Madeline Gilby, who worked in the Costcutter supermarket on the Old Kent Road and was disturbingly beautiful, even when she arrived still wearing her blue cashier's smock. Kate had known her for almost three years, and it had taken that long to convince her that she possessed a rare gift beyond that of her grace.

The small brown moth batted feebly once more, then sank to the tablecloth. It was losing strength. Madeline furrowed her brow and pressed pale hands to her temples, shutting her eyes tight.

"He's tiring. Keep concentrating."

The Broad-bar made one final attempt to escape through the top of the glass, and fell back. One wing ticked rapidly and then became still.

"That,"said Jessica, adjusting her great glasses, "shows the true intensity of the directed mind. The energy you generated is not measurable by any electronic means, and yet it's enough to interfere with the nervous system of this poor little creature. Of course, the test is hardly very scientific, but it suffices to demonstrate the power you hold within you."

Madeline was astonished. She gasped and smiled at the others.

"You have the gift, dear, as all women do in different degrees," said Kate. "In time, and with our help, you'll be able to identify the auras of others, seeing deep inside their hearts. You'll instinctively know if they mean you good or harm, and will never need to fear a man again. From now on, you and your son will be safe."

Kate was clear and confident, conscious of her middle-class enunciation. As a professional, she was used to being heard and obeyed. She turned to the others. "You see how easy it is to harness your inner self? It is important to understand that, in a manner of speaking, all women have two hearts. The first is the muscle that pumps our blood, and the second is a psychic heart that, if properly developed, opens us to secret knowledge. You can all harness that heart-power, just as Madeline is doing. Males don't possess this second spiritual heart; they have only flesh and bone. They feel pain and pleasure, but there is no extra dimension to their feelings, whereas we are able to find deeper shading in our emotional spirituality. This is the defence we develop against those who hurt us and our children, because most men do eventually, even if they never intend to. They are fundamentally different creatures, and fail to understand the damage they cause. With training, we can open a pathway illuminated by the pure light of truth, and see into the hearts of men. This is the breakthrough that Madeline has achieved today, in this room.?"

Madeline was unable to stop herself from crying. As a child she had been lonely and imaginative, used to spending long afternoons with books and make-believe friends until boys discovered her nascent beauty. Then the nightmare had begun. Now, there was a chance that it might really be over. For the first time since she had met Kate, she truly believed that her power existed.

"That's it, let it all out,"said her mentor, placing a plump arm around her as the others murmured their approval. "It always comes as a shock the first time. You'll get used to it."

Madeline needed air. She left the suffocating parlour and passed quickly through the herb-filled kitchen into the garden, where she found her son kicking sulkily at the flower beds that held etiolated rosebushes, each with a single despondent pink bloom.

"It's cold out here, Ryan. You should stay indoors."

"Her husband smokes."

"Even so." Madeline rubbed her bare arms briskly, looking about. The Anderson shelters and chicken sheds of postwar London had been replaced with rows of flat-pack conservatories. New attics and kitchens thrust out along the terrace, the residents pushing their property boundaries as if halfheartedly trying to break free of the past. "I'm ready to go now. Come and get your jacket. We'll go home."

As the neighbours gathered in the hall with their coats, Mrs Summerton removed the tumbler from the parlour table, crushing the moth between her thumb and forefinger before it had a chance to revive, flicking it into the waste bin. She had started her refuge over twenty years ago, when alcohol abuse had been the main problem. Now it was drugs, not that men needed to take stimulants before battering their partners. Madeline had come to her with a black eye and a sprained arm, but had still been anxious to get home on that first evening in order to cook her husband's dinner. Seeing the gratitude in her protegee's eyes made Kate sure she was doing the right thing, even if it meant performing a little parlour trick with a moth. Madeline was a good mother, kind and decent, but badly damaged by her relationships with men. If she could not be taught to seek independence and protect herself by traditional means, it was valid to introduce more unconventional methods. Mrs Summerton said her good-byes and closed the front door, then checked the time and went to change, remembering that someone new was coming to the shelter tonight. She only had room for eight women, and the new girl would make nine, but how would she ever forgive herself if she sent her home without help? Besides, the new girl came from a wealthy family; her fee could finance the refuge for months.

Mr Summerton stayed in the kitchen reading his paper. He had coped with the house being turned into a women's shelter, had even enjoyed it for a while, but now it was best to stay out of the way. His wife was honest down to her bones, he had always known that. She had made a few missteps in her overeagerness to help, that was all, but now she was exploring strange new territory, enjoining the women to discover their innate psychic powers and leave their husbands—encouraging suspicion and hatred of all men, of which he disapproved.

Still, she was a force of nature when she made up her mind, and he knew better than to raise his voice in protest. There had always been too many women in the house, Kate's friends, their daughters—even the cat was a female. His mother had once warned him that all women go mad eventually, and he was starting to believe it. Overlooked and outnumbered, he sipped his tea and turned to the sports pages.

Madeline walked home in the rain, clutching Ryan's hand too tightly. "Why are we walking?" asked the boy. "It's bloody freezing."

"Don't swear," his mother admonished. "I haven't got enough bus fare. It's not very far, and the exercise is good for you.?"

"That's because you gave all your money to her."

It was true that Mrs Summerton charged for her services, but you couldn't expect her to do it for nothing. Kate had made sense of her life. During her lonely childhood years, Madeline had been sure that some secret part of her was waiting to be discovered. But instead of gaining self-knowledge she became beautiful, and the curse began. Boys from her school hung around her house, laying their traps and baiting their lies with promises. She had even seen that terrible crafty gleam in her own father's eyes. She trusted easily, and was hurt each time. Beauty made her shy, and shyness made her controllable.

Now, at thirty years of age, she was finally discovering a way of standing up to the men who had always manipulated her. She owed Kate Summerton everything.

"Is she a lady doctor?"asked Ryan.

"Not exactly. What makes you think that?

"You went to see her when you hurt yourself."

Madeline had told her son that she'd fallen in the garden, and he seemed to believe her. "She was very kind to me," she said.

"You were ages in there," Ryan probed, watching her face in puzzlement. "I was stuck in the smoky kitchen with her horrible daughters and her boring husband. What were you doing?"

"Mrs Summerton was helping to teach me something."She was unsure about broaching the subject with her son. He was at the age where he seemed simultaneously too clever and too childish.

"You mean like school lessons?" Ryan persisted. 'What was she teaching you?'

Madeline remained quiet until they had turned the high corner wall of Greenwich Park. Winter mist was settling across the plane trees in a veil of dewdrops. "She was showing me how to deal with your father,?" she said at last.

Chapter Two

The Shaping of Men

Johann Bellocq stretched up on the staircase to the sea, and pulled another of the ripe orange loquats from the overhanging branches of the tree. Biting into them was like biting flesh. The juice ran down his chin, staining his blue nylon shirt, dripping darkly onto the hot steps. His stolen bounty held the sweet taste of sin. He spat the large stone at the landing below, watching it skitter and bounce into the storm drain, then loaded his pockets with all the sticky fruit he could touch on tiptoe. He was a tall, slim boy, and could reach into the dusty leaves for the most tender crops hidden from the flies and the harsh glare of the sun.

Summer had come early to la petite Afrique that year, encouraging his mother to keep the shutters closed, not that she needed much persuasion. She rarely allowed sunlight into the villa, so the rooms remained cold and damp-smelling deep into summer. Even when the mistral came, drawing dry northeasterly winds across the hills, she would not air the house. Thick yellow dust silted beneath the doors and across the window ledges, but she stubbornly refused to unseal the rooms. To allow nature in was to admit pagan forces, a blasphemous act of elemental obeisance that would disturb the pious sanctity of her home and unleash the powers of godlessness upon the three of them.

His mother was entirely mad.

Johann skipped up the steep staircase, noting the lowness of the sun in the cliffs above. He had no watch, but knew instinctively that his mother would be waiting to cruelly punish him. Today, though, he did not care.

He had just passed his twelfth birthday and was growing fast, already handsome, with a maturity beyond his age. Soon his grandfather would die, and he would be bigger than she. He could afford to bide his time.

He had stolen a transistor radio from one of the girls on the beach, and tuned it to a station that only played songs by the old French singers: Michel Delpech, Mireille Mathieu and Johnny Hallyday. He hated English bands, despised Culture Club and Queen, the arrogant regardez-moi prancing and posturing. He'd hidden the radio in the exhausted little orchard behind the house, where his mother would never find it. Pop was the Devil's music, and led to licentiousness, which was an old-fashioned word meaning sex. She would allow nothing in their home that might run the risk of destroying his innocence, because when boys discovered sex it turned their heads from God.

His stroke-afflicted grandfather, who lived with them, had ceased voicing his opinions, and spent his days drifting in dreams. Marcel's wife was dead, and he was not far behind. She had suffered cruelly with stomach cancer. If God was so merciful, why would he take two years to destroy a woman who had visited the little village church three times every Sunday and never uttered an unkind word in her life? Doubtless the old man would have liked to have asked his daughter this question, but knew all too well what she would say: God had tested her faith and found it wanting.

The house was tucked beneath umbrella pines and surrounded by twisted pale olive trees, their tortured roots thrust above the dry ground like ancient knees. Here the plants seeped pungent oils as a protection from the heat, as well as sharp-scented nectars that formed the bases for the area's perfume factories. No wooded aromas permeated the house, however. Perfume was the smell of sin, and was worn by the painted whores who paraded along the Avenue de la Californie after dark. His mother washed the edges of the doors and windows with disinfectant to keep the smell from entering.

Inside the little single-floored house, all was bare and white and pious. The rooms were scoured with bleach, the floors and steps with cleaning alcohol, the windows with paper and vinegar. In every room was a large pine crucifix, no other adornment. In the kitchen, a wooden table and three chairs, in the bedrooms iron bedsteads, narrow and rickety, topped with dented copper knobs, and above each bolster, a lurid picture of Our Lady, beatific and tortured, eyes rolled to Heaven. In his room, his mother had placed a faded Victorian sampler on the dresser, picked out in brown and white. Its stitched letters were a warning: "Dieu Voit Tout." God sees everything.

He hated the house, and longed to burn it to the ground. Soon the fierce cyanic blue of the Alpine skies would turn to grey, and winter would settle across the region, sealing them away from the world until spring. He would be left at the mercy of his mother. During the rare times when his grandfather was awake he protected the boy, but he was sleeping more and more, and could no longer be relied upon as a guardian.

Once, when Johann was seven years old, they had taken a holiday at Lac de l'Ascension, and his mother had pointed up into the dark sky, where rolling clouds had parted to release a shaft of sunlight down to the surface of the lake. "That," she told him, "is the pathway which leads directly to God. It is His way of watching all life on earth. He looks for those who flagrantly commit sin beneath His gaze, and punishes them."

"How does he do that, Mother?" asked Johann.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Blending humor and brilliant detection.... Fowler shows himself to be a master of the ‘impossible crime’ tale.... Excellent.”—Publishers Weekly, starred review

"Sherlock Holmes meets Inspector Clouseau in this mordant, award-winning series in which Fowler gleefully skewers religious zealots and government officials alike."—Booklist, starred review

“Chris Fowler is a master of the classical form.” —New York Times Book Review

“Ingenious.” —Denver Post

"Sherlock Holmes meets Inspector Clouseau in this mordant, award-winning series in which Fowler gleefully skewers religious zealots and government officials alike."—Booklist, starred review

“Chris Fowler is a master of the classical form.” —New York Times Book Review

“Ingenious.” —Denver Post