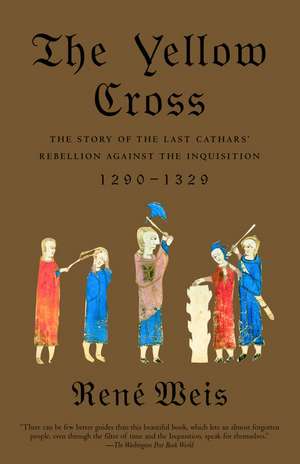

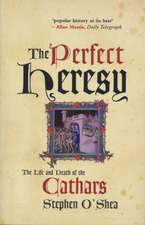

The Yellow Cross: The Story of the Last Cathars' Rebellion Against the Inquisition, 1290-1329

Autor Rene Weisen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 iul 2002

René Weis tells the dramatic and moving story of these thirty years, offering a rich medieval tale of faith, adventure, sex, and courage. Having spent years exploring a rich trove of untouched information, including trial records and interrogation transcripts, Weis creates a remarkably detailed portrait of the last great gasp of the movement and the day-to-day life of the individual Cathars in their villages. This is an exceptionally vivid re-creation of a fascinating, and otherwise lost, world.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 109.41 lei 6-8 săpt. | |

| Vintage Publishing – 31 iul 2002 | 115.32 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Penguin Books – aug 2001 | 109.41 lei 6-8 săpt. |

Preț: 115.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 173

Preț estimativ în valută:

22.07€ • 23.10$ • 18.26£

22.07€ • 23.10$ • 18.26£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780375704413

ISBN-10: 0375704418

Pagini: 468

Ilustrații: 16 PP. PHOTOS; 29 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 205 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books

Editura: Vintage Publishing

ISBN-10: 0375704418

Pagini: 468

Ilustrații: 16 PP. PHOTOS; 29 MAPS

Dimensiuni: 130 x 205 x 24 mm

Greutate: 0.42 kg

Ediția:Vintage Books

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Notă biografică

René Weis is Professor of English Literature at University College London. He is the author of numerous scholarly publications and of Criminal Justice: The True Story of Edith Thompson, published to critical acclaim in Britain in 1988.

From the Hardcover edition.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

Chapter 1

When B?atrice de Planisolles arrived in Montaillou to be married, the village counted some thirty-five separate family names and nearly fifty families, if the different branches of the same family are counted separately. The family names of Montaillou in the last decade of the thirteenth century were Argelier, Arzelier, Authi? (not related to the Axian Perfects and passim Authi? [B]), Az?ma, Baille, Bar, Belot, Benet, Bonclergue, Capelle, Caravessas, Castanier, Clergue, Clergue (B), Faure, Ferri?, Fort, Fournier, Guilabert, Julia, Lizier, Mamol (?), Martre, Marty, Maurs, Maury, Moyshen, P?lissier, Pourcel, Rives, Rous (alias "Colel"), Savenac, Tavernier (?), Teisseyre, Trilhe (or Trialh?), and Vital.

For the purpose of counting the people of Montaillou over a period of eighteen years, the years from c. 1291, the arrival of B?atrice, to 1308, the year the village was raided, seem an appropriate time-span since they coincide with the main Cathar episode. In this period the majority of the villagers whom we will encounter in these pages were born, or grew from their teens and twenties into early middle age. My focus therefore will be mostly the 1280s to mid-1290s generation.

Some 160 of the men, women and children of Montaillou can be identified by name, and there were probably some 250 people living in the village, if the average household is conservatively estimated at five bodies, to include two parents and at least three children per family. Various illegitimate children as well as grandparents and servants were also looked after in nuclear families. In addition there may have been a handful of families residing in the village whose presence is not specifically recorded in the Registers. And the figure of 250 does not include the occupants of the castle, the ch?telaine, her husband, their children and their staff.

In this deeply rural culture men and women needed to be able to depend mutually on one another for survival, hence family links were a bastion of strength. It was the blood ties between clans and families that ultimately provided the Authi?s, and other local Perfects such as Prades Tavernier, Pons Sicre and Arnaud Marty, with a century-old safety net that could never quite be shredded by the Inquisition. Even the Bishop of Pamiers would be aided in his task by family connections. For that reason it is essential to map out the major families of Montaillou before proceeding any further; families from other villages and towns, notably Prades, Ax, Luzenac, Larnat, Tarascon and Junac, and from the Toulousain also played a leading role in the dissemination of Catharism, and they will be met in due course.

Although it is not possible to locate with certainty the whereabouts in the village of all the participants, the homes of the most important among them can be identified on the grid with some confidence (Map 3). My conclusions are generated from a mosaic of mutually corroborative, and mostly incidental, remarks by various witnesses. These are crucially complemented by a striking passage in Pierre Maury's testimony, which appears to offer a semi-structured survey of the village's households (FR, f.257v; see below, page 34). It is a major source for confirming and, in some cases, determining the location in Montaillou of several among the lesser houses in the village.

In the 1290s and in the early years of the fourteenth century Montaillou was dominated by four powerful and variously affluent clans whose houses clustered in the vicinity of the square of Montaillou. They were called Belot, Benet, Rives and Clergue.

The Cathar trio and the Clergues

The houses of the Belots, Benets and Rives were built into the slope of the hill on the north-western side of the main artery so that their fronts faced south or south-east. These properties occupied the space between the junction of capanal den belot and the village square itself, and they were easily overlooked from the plateau. In clement weather their back-roofs provided a favourite place for the social and physical ritual of mutual delousing. All three were substantial dwellings with barns, vegetable gardens and dry-walled courtyards with gates or portals which verged on the village's track. Even the poorer houses of Montaillou usually had vegetable and herb gardens at the front, as did some of the houses in the square. Some properties, like the P?lissiers', were separated from the road by hedges.

The Belots: This large house was low-roofed (bassum) at the back, because of the slope and the convex arching of the "inner" path to Prades which ran down past it into capanal den belot (FR, f.60v). In front of its substantial porch extended the Belots' south-east-facing courtyard, which overlooked the Clergues. It was an obvious place for gossiping matriarchs to take the sun. Slightly apart from the porch was a spot called "las penas," which may have been reserved for servants, and from here the servants would eavesdrop on their mistress's conversations. The Belots were the second-wealthiest clan in the village. They were rich enough to recruit and employ servants, and the boundaries between servant and master were repeatedly transgressed in this household, which was a hive of sexual activity.

There were two parents, four sons and two (or perhaps three) daughters.The sons were called Raymond, Bernard, Guillaume and Arnaud, and the daughters were Raymonde and Alazais, and perhaps Arnaude. The Belot patriarch's name is not known, but he may have been dead by the end of the 1290s because by then the Belots' house was commonly called "Raymond Belot's house," which probably indicates that Raymond was the eldest son and the new head of the family; unless, of course, the father was also called Raymond, in which case the name of the house simply continued. That the Belot brothers Raymond and Bernard shared the house as owners was noted by the new ch?telaine when she lived in the village during this period. The younger Belot brothers were ruffians, and while Bernard Belot sexually assaulted the wife of another Montalionian, his brother Arnaud fathered an illegitimate child called ?tienne when he was still, it seems, in his teens. The Belot mother was called Guillemette, and she would have been in her forties or early fifties in the 1290s. She was on intimate terms with her neighbour and contemporary Mengarde Clergue, the matriarch of the richest and most powerful family in Montaillou. In their devotion to the Cathar cause the Belots did not lag far behind the illustriously connected Benets.

The Benets: The Benets' house stood a few yards north-east and down the hill from the Belots'. It was their home which provided the initial channel for the Cathar reawakening in Montaillou, because Guillaume Benet of Montaillou was the uncle of the Perfect Guillaume Authi?'s wife.

Guillaume and Guillemette Benet had three sons and four daughters. When Montane Benet was born c. 1301-2 her sisters Esclarmonde and Guillemette were "little girls," and her brother Bernard was still only a child in 1308. The relative youth of the Benet children suggests that Guillemette, the mother of the household, was younger than either of the neighbouring matriarchs Guillemette Belot and Mengarde Clergue, who were direct contemporaries. Guillemette Benet may not have been much older than B?atrice de Planisolles. She repeatedly expressed her horror of the pain inflicted by fire, and later had to endure the agony of seeing her brother-in-law being burnt at the stake.

Whereas all the major houses owned livestock and farmed, there was also a need for skilled craftsmen. Just as there were weavers in the village, so the Benets may have been builders, that is masons or roofers, because they owned tools. It is significant that the rich Belots' extension was built for them rather than by them, which suggests that a labour market operated in Montaillou. The wood for roofing, barns and enclosures came from the plentiful thick forests to the south-east of the village. As the wheel does not seem to have existed in the Pays d'Aillou in the thirteenth century, tree trunks needed either to be dragged into the village by oxen, or transported on the back of mules.

The Rives: The house of Bernard and Alazais Rives was the next one down from the Benets', and was in fact partly terraced with it. Theirs was a large and wealthy corner-house at the intersection of the main artery of Montaillou and the south-eastern side of the village square, and it could be entered either from the square or from the road. Its front boasted a porch where picked vegetables and fruit were kept. It had interior stables for beasts whose waste was carried outside through the main entrance of the house and deposited on a dunghill in the courtyard on the side of the square. The Rives also owned a barn which was an extension of the house while having a separate outside entrance. In this place, which had a skylight, grass and bales of hay and straw were stored.

We have already noted that the house contained a much-used bread-oven, which was in a roomy space serving as both hearth and dining-room. The Occitan term for this nerve centre of a thirteenth-century Sabartesian house was foghana. To translate it as "kitchen," as Pales-Gobilliard does, fails to convey its importance as the preferred area for eating and sitting as well as for cooking, drying meat and baking, and for laying out the dead. It was in the foghana that life was played out during the winter, when the gossips gathered around the fire, and the bedrooms as well as the stables were usually off it. For these reasons I propose to retain the Occitan phrase to denote this inclusive core area where so many key events took place.

The Rives owed their economic importance to their local landholding. They were prosperous farmers, who also kept animals for food and work; and they were active weavers. Next to the main Rives property, in the square of Montaillou itself, stood a junior Rives house which probably belonged to Bernard's brother Raymond Rives. The two Rives houses may have been almost merged into one. If so, they formed an impressive block which took in the south-eastern corner of the square and a section of its southern side.

By 1291 the senior Rives were linked, through the marriage of Bernard Rives of Montaillou and Alazais Tavernier of Prades, to a family of thriving weavers from neighbouring Prades. The couple had a son, Pons, and three daughters, of whom the youngest, Guillemette, was about eleven years old in 1291; she would later provide some of the most fascinating details about daily life in Montaillou. By marrying Alazais Tavernier, Bernard Rives had joined a committed Cathar family, because Alazais's brother was the weaver and future Perfect Prades Tavernier. Consequently the Rives house would become as much of a focus for heresy as its direct neighbour, the Benets'. Indeed, it was at the Rives' that the Perfects set up a small Cathar chapel, and the Rives and Benet houses were eventually connected by a secret passage which, through a movable partition, led from the Rives' house into a room off the Benets' foghana.

the clergues: In the late thirteenth century there were at least five families by the name of Clergue in the village, two of which are called Clergue (B) in this book to distinguish them from the main Clergue family.

The two branches of the pre-eminent family were those of Pons Clergue and his wife Mengarde, who was a Martre from the neighbouring village of Camurac, and the truncated family of Pons's (unmarried?) brother Guillaume and his two illegitimate children Fabrisse and Raymond, who was also known as "Pathau." This may be the name of his mother's family (there were Pathaus in Ax), or "pathau" may correspond to modern French "pataud" (LT), which means lumpish or oafish. It was Raymond Pathau who would assault the new ch?telaine. The third Clergue family in Montaillou, which was headed by one Arnaud Clergue, was only tenuously related to the others. None of these families seems to have had family ties with the Clergue (B) family into which Guillemette Rives, one of our key witnesses, married.

the main clergue family: Pons Clergue and Mengarde Martre had four sons and two daughters, and they lived opposite the Belots in a large two-floor house which probably sat on top of a cellar and stables. Both the Clergue parents were uncompromisingly Cathar, and Mengarde was close to a notorious Cathar matriarch from Montaillou called Na (i.e., "domina") Roche.

Among the Clergues' four male offspring the eldest was Pierre Clergue, who became the village priest. He remains to this day the most infamous son of Montaillou. The next was Bernard who, before the Carcassonne Inquisition, cast himself as an inveterate romantic. This canard, which Bernard Clergue peddled successfully to the Inquisition, seems also to have fooled twentieth-century students of the documents. He was ruthless, adored his elder brother Pierre, and was the bajulus or bayle of Montaillou. As such, he was invested locally with the authority of the Count of Foix, and his brief included administrative duties and judicial powers of arrest. He was the village's chief constable. He was also the father of an illegitimate daughter whom, as a dutiful son, he named Mengarde after his mother; and young Mengarde worked as a servant in the large Clergue household.

The two senior Clergue brothers were probably in their late teens when the new ch?telaine arrived in Montaillou in 1291. They would prove to be, in the words of one of their contemporaries, a "mala cadelada," that is, a "bad brood" or a "bad bitch's litter." While Pierre Clergue seems to have been absent from Montaillou during the first half of the last decade of the thirteenth century, his younger brothers Bernard, Guillaume and Raymond as well as his sisters Guillemette and Esclarmonde probably lived in the village. The two sisters, however, married before the end of the century and left the village during the 1290s.*

While their neighbours were doing well, the Clergues were truly rich. Over the years they lined the pockets of some of the highest officials of the Inquisition in Pamiers, Carcassonne and even Toulouse with princely bribes. The source of their wealth remains a mystery, but it is a fair guess that it originated from three generations of two-timing the Inquisition.

A fatal flaw in the Inquisition's operational network was its dependency on the local clergy for the issuing of summonses and for monitoring the observance of its decrees. This allowed families like the Clergues to play both sides and operate lucrative protection rackets. In spite of their wealth, however, the Clergues, like the semi-literate Sicilian godfathers of a later age, remained stubbornly rooted in their fee.

From the Hardcover edition.

When B?atrice de Planisolles arrived in Montaillou to be married, the village counted some thirty-five separate family names and nearly fifty families, if the different branches of the same family are counted separately. The family names of Montaillou in the last decade of the thirteenth century were Argelier, Arzelier, Authi? (not related to the Axian Perfects and passim Authi? [B]), Az?ma, Baille, Bar, Belot, Benet, Bonclergue, Capelle, Caravessas, Castanier, Clergue, Clergue (B), Faure, Ferri?, Fort, Fournier, Guilabert, Julia, Lizier, Mamol (?), Martre, Marty, Maurs, Maury, Moyshen, P?lissier, Pourcel, Rives, Rous (alias "Colel"), Savenac, Tavernier (?), Teisseyre, Trilhe (or Trialh?), and Vital.

For the purpose of counting the people of Montaillou over a period of eighteen years, the years from c. 1291, the arrival of B?atrice, to 1308, the year the village was raided, seem an appropriate time-span since they coincide with the main Cathar episode. In this period the majority of the villagers whom we will encounter in these pages were born, or grew from their teens and twenties into early middle age. My focus therefore will be mostly the 1280s to mid-1290s generation.

Some 160 of the men, women and children of Montaillou can be identified by name, and there were probably some 250 people living in the village, if the average household is conservatively estimated at five bodies, to include two parents and at least three children per family. Various illegitimate children as well as grandparents and servants were also looked after in nuclear families. In addition there may have been a handful of families residing in the village whose presence is not specifically recorded in the Registers. And the figure of 250 does not include the occupants of the castle, the ch?telaine, her husband, their children and their staff.

In this deeply rural culture men and women needed to be able to depend mutually on one another for survival, hence family links were a bastion of strength. It was the blood ties between clans and families that ultimately provided the Authi?s, and other local Perfects such as Prades Tavernier, Pons Sicre and Arnaud Marty, with a century-old safety net that could never quite be shredded by the Inquisition. Even the Bishop of Pamiers would be aided in his task by family connections. For that reason it is essential to map out the major families of Montaillou before proceeding any further; families from other villages and towns, notably Prades, Ax, Luzenac, Larnat, Tarascon and Junac, and from the Toulousain also played a leading role in the dissemination of Catharism, and they will be met in due course.

Although it is not possible to locate with certainty the whereabouts in the village of all the participants, the homes of the most important among them can be identified on the grid with some confidence (Map 3). My conclusions are generated from a mosaic of mutually corroborative, and mostly incidental, remarks by various witnesses. These are crucially complemented by a striking passage in Pierre Maury's testimony, which appears to offer a semi-structured survey of the village's households (FR, f.257v; see below, page 34). It is a major source for confirming and, in some cases, determining the location in Montaillou of several among the lesser houses in the village.

In the 1290s and in the early years of the fourteenth century Montaillou was dominated by four powerful and variously affluent clans whose houses clustered in the vicinity of the square of Montaillou. They were called Belot, Benet, Rives and Clergue.

The Cathar trio and the Clergues

The houses of the Belots, Benets and Rives were built into the slope of the hill on the north-western side of the main artery so that their fronts faced south or south-east. These properties occupied the space between the junction of capanal den belot and the village square itself, and they were easily overlooked from the plateau. In clement weather their back-roofs provided a favourite place for the social and physical ritual of mutual delousing. All three were substantial dwellings with barns, vegetable gardens and dry-walled courtyards with gates or portals which verged on the village's track. Even the poorer houses of Montaillou usually had vegetable and herb gardens at the front, as did some of the houses in the square. Some properties, like the P?lissiers', were separated from the road by hedges.

The Belots: This large house was low-roofed (bassum) at the back, because of the slope and the convex arching of the "inner" path to Prades which ran down past it into capanal den belot (FR, f.60v). In front of its substantial porch extended the Belots' south-east-facing courtyard, which overlooked the Clergues. It was an obvious place for gossiping matriarchs to take the sun. Slightly apart from the porch was a spot called "las penas," which may have been reserved for servants, and from here the servants would eavesdrop on their mistress's conversations. The Belots were the second-wealthiest clan in the village. They were rich enough to recruit and employ servants, and the boundaries between servant and master were repeatedly transgressed in this household, which was a hive of sexual activity.

There were two parents, four sons and two (or perhaps three) daughters.The sons were called Raymond, Bernard, Guillaume and Arnaud, and the daughters were Raymonde and Alazais, and perhaps Arnaude. The Belot patriarch's name is not known, but he may have been dead by the end of the 1290s because by then the Belots' house was commonly called "Raymond Belot's house," which probably indicates that Raymond was the eldest son and the new head of the family; unless, of course, the father was also called Raymond, in which case the name of the house simply continued. That the Belot brothers Raymond and Bernard shared the house as owners was noted by the new ch?telaine when she lived in the village during this period. The younger Belot brothers were ruffians, and while Bernard Belot sexually assaulted the wife of another Montalionian, his brother Arnaud fathered an illegitimate child called ?tienne when he was still, it seems, in his teens. The Belot mother was called Guillemette, and she would have been in her forties or early fifties in the 1290s. She was on intimate terms with her neighbour and contemporary Mengarde Clergue, the matriarch of the richest and most powerful family in Montaillou. In their devotion to the Cathar cause the Belots did not lag far behind the illustriously connected Benets.

The Benets: The Benets' house stood a few yards north-east and down the hill from the Belots'. It was their home which provided the initial channel for the Cathar reawakening in Montaillou, because Guillaume Benet of Montaillou was the uncle of the Perfect Guillaume Authi?'s wife.

Guillaume and Guillemette Benet had three sons and four daughters. When Montane Benet was born c. 1301-2 her sisters Esclarmonde and Guillemette were "little girls," and her brother Bernard was still only a child in 1308. The relative youth of the Benet children suggests that Guillemette, the mother of the household, was younger than either of the neighbouring matriarchs Guillemette Belot and Mengarde Clergue, who were direct contemporaries. Guillemette Benet may not have been much older than B?atrice de Planisolles. She repeatedly expressed her horror of the pain inflicted by fire, and later had to endure the agony of seeing her brother-in-law being burnt at the stake.

Whereas all the major houses owned livestock and farmed, there was also a need for skilled craftsmen. Just as there were weavers in the village, so the Benets may have been builders, that is masons or roofers, because they owned tools. It is significant that the rich Belots' extension was built for them rather than by them, which suggests that a labour market operated in Montaillou. The wood for roofing, barns and enclosures came from the plentiful thick forests to the south-east of the village. As the wheel does not seem to have existed in the Pays d'Aillou in the thirteenth century, tree trunks needed either to be dragged into the village by oxen, or transported on the back of mules.

The Rives: The house of Bernard and Alazais Rives was the next one down from the Benets', and was in fact partly terraced with it. Theirs was a large and wealthy corner-house at the intersection of the main artery of Montaillou and the south-eastern side of the village square, and it could be entered either from the square or from the road. Its front boasted a porch where picked vegetables and fruit were kept. It had interior stables for beasts whose waste was carried outside through the main entrance of the house and deposited on a dunghill in the courtyard on the side of the square. The Rives also owned a barn which was an extension of the house while having a separate outside entrance. In this place, which had a skylight, grass and bales of hay and straw were stored.

We have already noted that the house contained a much-used bread-oven, which was in a roomy space serving as both hearth and dining-room. The Occitan term for this nerve centre of a thirteenth-century Sabartesian house was foghana. To translate it as "kitchen," as Pales-Gobilliard does, fails to convey its importance as the preferred area for eating and sitting as well as for cooking, drying meat and baking, and for laying out the dead. It was in the foghana that life was played out during the winter, when the gossips gathered around the fire, and the bedrooms as well as the stables were usually off it. For these reasons I propose to retain the Occitan phrase to denote this inclusive core area where so many key events took place.

The Rives owed their economic importance to their local landholding. They were prosperous farmers, who also kept animals for food and work; and they were active weavers. Next to the main Rives property, in the square of Montaillou itself, stood a junior Rives house which probably belonged to Bernard's brother Raymond Rives. The two Rives houses may have been almost merged into one. If so, they formed an impressive block which took in the south-eastern corner of the square and a section of its southern side.

By 1291 the senior Rives were linked, through the marriage of Bernard Rives of Montaillou and Alazais Tavernier of Prades, to a family of thriving weavers from neighbouring Prades. The couple had a son, Pons, and three daughters, of whom the youngest, Guillemette, was about eleven years old in 1291; she would later provide some of the most fascinating details about daily life in Montaillou. By marrying Alazais Tavernier, Bernard Rives had joined a committed Cathar family, because Alazais's brother was the weaver and future Perfect Prades Tavernier. Consequently the Rives house would become as much of a focus for heresy as its direct neighbour, the Benets'. Indeed, it was at the Rives' that the Perfects set up a small Cathar chapel, and the Rives and Benet houses were eventually connected by a secret passage which, through a movable partition, led from the Rives' house into a room off the Benets' foghana.

the clergues: In the late thirteenth century there were at least five families by the name of Clergue in the village, two of which are called Clergue (B) in this book to distinguish them from the main Clergue family.

The two branches of the pre-eminent family were those of Pons Clergue and his wife Mengarde, who was a Martre from the neighbouring village of Camurac, and the truncated family of Pons's (unmarried?) brother Guillaume and his two illegitimate children Fabrisse and Raymond, who was also known as "Pathau." This may be the name of his mother's family (there were Pathaus in Ax), or "pathau" may correspond to modern French "pataud" (LT), which means lumpish or oafish. It was Raymond Pathau who would assault the new ch?telaine. The third Clergue family in Montaillou, which was headed by one Arnaud Clergue, was only tenuously related to the others. None of these families seems to have had family ties with the Clergue (B) family into which Guillemette Rives, one of our key witnesses, married.

the main clergue family: Pons Clergue and Mengarde Martre had four sons and two daughters, and they lived opposite the Belots in a large two-floor house which probably sat on top of a cellar and stables. Both the Clergue parents were uncompromisingly Cathar, and Mengarde was close to a notorious Cathar matriarch from Montaillou called Na (i.e., "domina") Roche.

Among the Clergues' four male offspring the eldest was Pierre Clergue, who became the village priest. He remains to this day the most infamous son of Montaillou. The next was Bernard who, before the Carcassonne Inquisition, cast himself as an inveterate romantic. This canard, which Bernard Clergue peddled successfully to the Inquisition, seems also to have fooled twentieth-century students of the documents. He was ruthless, adored his elder brother Pierre, and was the bajulus or bayle of Montaillou. As such, he was invested locally with the authority of the Count of Foix, and his brief included administrative duties and judicial powers of arrest. He was the village's chief constable. He was also the father of an illegitimate daughter whom, as a dutiful son, he named Mengarde after his mother; and young Mengarde worked as a servant in the large Clergue household.

The two senior Clergue brothers were probably in their late teens when the new ch?telaine arrived in Montaillou in 1291. They would prove to be, in the words of one of their contemporaries, a "mala cadelada," that is, a "bad brood" or a "bad bitch's litter." While Pierre Clergue seems to have been absent from Montaillou during the first half of the last decade of the thirteenth century, his younger brothers Bernard, Guillaume and Raymond as well as his sisters Guillemette and Esclarmonde probably lived in the village. The two sisters, however, married before the end of the century and left the village during the 1290s.*

While their neighbours were doing well, the Clergues were truly rich. Over the years they lined the pockets of some of the highest officials of the Inquisition in Pamiers, Carcassonne and even Toulouse with princely bribes. The source of their wealth remains a mystery, but it is a fair guess that it originated from three generations of two-timing the Inquisition.

A fatal flaw in the Inquisition's operational network was its dependency on the local clergy for the issuing of summonses and for monitoring the observance of its decrees. This allowed families like the Clergues to play both sides and operate lucrative protection rackets. In spite of their wealth, however, the Clergues, like the semi-literate Sicilian godfathers of a later age, remained stubbornly rooted in their fee.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“There can be fewer better guides than this beautiful book, which lets an almost forgotten people, even through the filter of time and the Inquisition, speak for themselves.” —The Washington Post Book World

"In a feat of inspired scholarship, Weis transports us back to that world, conveying all of the high drama of ecclesiastical interrogations, covert ceremonies, and fiery martyrdom. . . . A book that will long haunt its readers."--Booklist

"This book reanimates the real world of the Cathars of seven hundred years ago in a way that is fresh, utterly modern, and pulsates with life."–Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, author of Montaillou

"It succeeds enthrallingly . . . a moving evocation of an almost inconceivable faith."--The Times (London)

"In a feat of inspired scholarship, Weis transports us back to that world, conveying all of the high drama of ecclesiastical interrogations, covert ceremonies, and fiery martyrdom. . . . A book that will long haunt its readers."--Booklist

"This book reanimates the real world of the Cathars of seven hundred years ago in a way that is fresh, utterly modern, and pulsates with life."–Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie, author of Montaillou

"It succeeds enthrallingly . . . a moving evocation of an almost inconceivable faith."--The Times (London)

Descriere

Remarkable for both its details about life in a medieval village and the tragic story it recounts, "The Yellow Cross" is an achievement of scholarship and historical narrative. The author re-creates the Cathars' final struggle and offers a moving portrait of a people and their day-to-day lives.