Unto the Sons

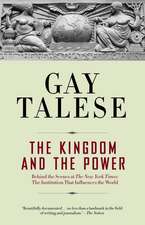

Autor Gay Taleseen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 1995

At long last, Gay Talese, one of America's greatest living authors, employs his prodigious storytelling gifts to tell the saga of his own family's emigration to America from Italy in the years preceding World War II. Ultimately it is the story of all immigrant families and the hope and sacrifice that took them from the familiarity of the old world into the mysteries and challenges of the new.

From the Paperback edition.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 141.23 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Random House Trade – 31 mar 2006 | 141.23 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| BALLANTINE BOOKS – 28 feb 1995 | 183.66 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 183.66 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 275

Preț estimativ în valută:

35.15€ • 36.65$ • 29.21£

35.15€ • 36.65$ • 29.21£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 februarie-14 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780345463425

ISBN-10: 0345463420

Pagini: 640

Dimensiuni: 152 x 219 x 39 mm

Greutate: 0.81 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

ISBN-10: 0345463420

Pagini: 640

Dimensiuni: 152 x 219 x 39 mm

Greutate: 0.81 kg

Editura: BALLANTINE BOOKS

Extras

1.

The beach in winter was dank and desolate, and the island dampened by the frigid spray of the ocean waves pounding relentlessly against the beachfront bulkheads, and the seaweed-covered beams beneath the white houses on the dunes creaked as quietly as the crabs crawling nearby.

The boardwalk that in summer was a festive promenade of suntanned couples and children’s balloons, of carousel tunes and colored lights spinning at night from the Ferris wheel, was occupied in winter by hundreds of sea gulls perched on the iron railings facing into the wind. When not resting they strutted outside the locked doors of vacated shops, or circled high in the sky, holding clams in their beaks that they soon dropped upon the boardwalk with a splattering cluck. Then they zoomed down and pounced on the exposed meat, pecking and pulling until there was nothing left but the jagged, salty white chips of empty shells.

By midwinter the shell-strewn promenade was a vast cemetery of clams, and from a distance the long elevated flat deck of the boardwalk resembled a stranded aircraft carrier being attacked by dive-bombers—and oddly juxtaposed in the fog behind the dunes loomed the rusting remains of a once sleek four-masted vessel that during a gale in the winter of 1901 had run aground on this small island in southern New Jersey called Ocean City.

The steel-hulled ship, flying a British flag and flaunting hundred-fifty-foot masts, had been sailing north along the New Jersey coast toward New York City, where it was scheduled to deliver one million dollars’ worth of Christmas cargo it had picked up five months before in Kobe, Japan. But during the middle of the night, while a number of crewmen drank rum and beer in a premature toast to the long journey’s end, a fierce storm rose and destroyed the ship’s sails, snapped its masts, and drove it into a sandbar within one hundred yards of the Ocean City boardwalk.

Awakened by the distress signals that flared in the night, the alarmed residents of Ocean City—a conservative community founded in 1879 by Methodist ministers and other Prohibitionists who wished to establish an island of abstinence and propriety—hastened to help the sailors, who were soon discovered to be battered but unharmed and smelling of sweat, salt water, and liquor.

After the entire thirty-three-man crew had been escorted to shore, they were sheltered and fed for days under the auspices of the town’s teetotaling elders and ministers’ wives; and while the sailors expressed gratitude for such hospitality they privately cursed their fate in being shipwrecked on an island so sedate and sober. But soon they were relocated by British nautical authorities, and the salvageable cargo was barged to New York to be sold at reduced prices. And the town returned to the tedium of winter.

The big ship, however, remained forever lodged in the soft white sand—unmovable, slowly sinking, a sight that served Ocean City’s pious guardians as a daily reminder of the grim consequences of intemperate guidance. But as I grew up in the late 1930s, more than three decades after the shipwreck—when the visible remnants at low tide consisted only of the barnacle-bitten ridge of the upper deck, the corroded brown rudder post and tiller, and a single lopsided mast—I viewed the vessel as a symbol of adventure and risk; and during my boyhood wanderings along the beach I became enchanted with exotic fantasies of nights in foreign ports, of braving the waves and wind with wayward men, and of escaping the rigid confines of this island on which I was born but never believed I belonged.

I saw myself always as an alien, an outsider, a drifter who, like the shipwrecked sailors, had arrived by accident. I felt different from my young friends in almost every way, different in the cut of my clothes, the food in my lunch box, the music I heard at home on the record player, the ideas and inner thoughts I revealed on those rare occasions when I was open and honest.

I was olive-skinned in a freckle-faced town, and I felt unrelated even to my parents, especially my father, who was indeed a foreigner—an unusual man in dress and manner, to whom I bore no physical resemblance and with whom I could never identify. Trim and elegant, with wavy dark hair and a small rust-colored moustache, he spoke English with an accent and received letters bearing strange-looking stamps.

These letters sometimes contained snapshots of soldiers wearing uniforms with insignia and epaulets unlike any I had seen on the recruit- ment posters displayed throughout the island. They were my uncles and cousins, my father explained to me quietly one day early in World War II, when I was ten; they were fighting in the Italian army, and—it was unnecessary for him to add—their enemy included the government of the United States.

I became increasingly sensitive to this fact when I sat through the newsreels each week at the local cinema; next to my unknowing classmates, I watched with private horror the destruction by Allied bombers of mountain villages and towns in southern Italy to which I was ancestrally linked through a historically ill-timed relationship with my Italian father. At any moment I half expected to see up on the screen, gazing down at me from a dust-covered United States Army truck filled with disheveled Italian prisoners being guarded at gunpoint, a sad face that I could identify from one of my father’s snapshots.

My father, on the other hand, seemed to share none of my confused sense of patriotism during the war years. He joined a citizens’ committee of shore patrolmen who kept watch along the waterfront at night, standing with binoculars on the boardwalk under the stanchioned lights that on the ocean side were painted black as a precaution against discovery by enemy submarines.

He made headlines in the local newspaper after a popular speech to the Rotary Club in which he reaffirmed his loyalty to the Allied cause, declaring that were he not too old for the draft (he was thirty-nine) he would proudly join the American troops at the front, in a uniform devotedly cut and stitched with his own hands.

Trained as an apprentice tailor in his native village, and later an assistant cutter in a prominent shop in Paris that employed an older Italian cousin, my father arrived in Ocean City circuitously and impulsively at the age of eighteen in 1922 with very little money, an extensive wardrobe, and the outward appearance of a man who knew exactly where he was going, when in fact nothing was further from the truth. He knew no one in town, barely knew the language, and yet, with a self-assurance that has always mystified me, he adjusted to this unusual island as readily as he could cut cloth to fit any size and shape.

Having noticed a “For Sale” sign in the window of a tailor shop in the center of town, my father approached the asthmatic owner, who was desperate to leave the island for the drier climate of Arizona. After a brief negotiation, my father acquired the business and thus began a lengthy, spirited campaign to bring the rakish fashion of the Continental boulevardier to the comparatively continent men of the south Jersey shore.

But after decorating his windows with lantern-jawed mannequins holding cigarettes and wearing Borsalino hats, and draping his counters with bolts of fine imported fabrics—and displaying on his walls such presumably persuasive regalia as his French master tailor’s diploma bordered by cherubim and a Greek goddess—my father made so few sales during his first year that he was finally forced to introduce into his shop a somewhat undignified gimmick called the Suit Club.

At the cost of one dollar per week, Suit Club members would print their names and addresses on small white cards and, after placing the cards in unmarked envelopes, would deposit them into a large opaque vase placed prominently atop a velvet-covered table next to a fashion photograph of a dapper man and woman posing with a greyhound on the greensward of an ornate country manor.

Each Friday evening just prior to closing time, my father would invite one of the assembled Suit Club members to close his eyes and pick from the vase a single envelope, which would reveal the name of the fortunate winner of a free suit, to be made from fabric selected by that individual; after two fittings, it would be ready for wearing within a week.

Since as many as three or four hundred people were soon paying a dollar each week to partake in this raffle, my father was earning on each free suit a profit perhaps three times the average cost of a custom-made suit in those days—to say nothing of the additional money he earned when he enticed a male winner into purchasing an extra pair of matching trousers.

But my father’s bonanza was abruptly terminated one day in 1928, when an anonymous complaint sent to City Hall, possibly by a rival tailor, charged that the Suit Club was a form of gambling clearly outlawed under the town charter; thus ended for all time my father’s full-time commitment to the reputable but precarious life of an artist with a needle and thread. My father did not climb down from an impoverished mountain in southern Italy and forsake the glorious lights of Paris and sail thousands of miles to the more opportunistic shores of America to end up as a poor tailor in Ocean City, New Jersey.

So he diversified. Advertising himself as a ladies’ furrier who could alter or remodel old coats as well as provide resplendent new ones (which he obtained on consignment from a Russian Jewish immigrant who resided in nearby Atlantic City), my father expanded his store to accommodate a refrigerated fur storage vault and extended the rear of the building to include a dry-cleaning plant overseen by a black Baptist deacon who during Prohibition operated a small side business in bootlegging. Later, in the 1930s, my father added a ladies’ dress boutique, having as partner and wife a well-tailored woman who once worked as a buyer in a large department store in Brooklyn.

He met her while attending an Italian wedding in that borough in December 1927. She was a bridesmaid, a graceful and slender woman of twenty with dark eyes and fair complexion and a style my father immediately recognized as both feminine and prepossessing. After a few dances at the reception under the scrutiny of her parents, and the frowns of the saxophone player in the band with whom she had recently gone out on a discreet double date, my father decided to delay his departure from Brooklyn for a day or two so that he might ingratiate himself with her. This he did with such panache that they were engaged within a year, and married six months later, after buying a small white house near the Ocean City beach, where, in the winter of 1932, I was born and awoke each morning to the smell of espresso and the roaring sound of the waves.

My first recollection of my mother was of a fashionable, solitary figure on the breezy boardwalk pushing a baby carriage with one hand while with the other stabilizing on her head a modish feathered hat at an unwavering angle against the will of the wind.

As I grew older I learned that she cared greatly about exactness in appearance, preciseness in fit, straightness in seams; and, except when positioned on a pedestal in the store as my father measured her for a new suit, she seemed to prefer standing at a distance from other people, conversing with customers over a counter, communicating with her friends via telephone rather than in person. On those infrequent occasions when her relatives from Brooklyn would visit us in Ocean City, I noticed how quickly she backed away from their touch after offering her cheek for a kiss of greeting. Once, during my preschool days as I accompanied her on an errand, I tried to hold on to her, to put my hand inside the pocket of her coat not only for the warmth but for a closer feeling with her presence. But when I tried this I felt her hand, gently but firmly, remove my own.

It was as if she were incapable of intimate contact with anyone but my father, whom she plainly adored to the exclusion of everyone else; and the impression persisted throughout my youth that I was a kind of orphan in the custody of a compatible couple whose way of life was strange and baffling.

One night at the dinner table when I casually picked up a loaf of Italian bread and placed it upside down in the basket, my father became furious and, without further explanation, turned the loaf right side up and demanded that I never repeat what I had done. Whenever we attended the cinema as a family we left before the end, possibly because of my parents’ inability or unwillingness to relate to the film’s content, be it drama or comedy. And although my parents spent their entire married life living along the sea, I never saw them go sailing, fishing, or swimming, and rarely did they even venture onto the beach itself.

In my mother’s case I suspect her avoidance of the beach was due to her desire to prevent the sun from scorching and darkening her fair skin. But I believe my father’s aversion to the sea was based on something deeper, more complex, somehow related to his boyhood in southern Italy. I suggest this because I often heard him refer to his region’s coastline as foreboding and malarial, a place of piracy and invasion; and as an avid reader of Greek mythology—his birthplace is not far from the renowned rock of Scylla, where the Homeric sea monster devoured sailors who had escaped the whirlpool of Charybdis—my father was prone to attaching chimerical significance to certain bizarre or inexplicable events that occurred during his youth along the streams and lakes below his village.

I remember overhearing, when I was eleven or twelve, my father complaining to my mother that he had just experienced a sleepless night during which he had been disturbed by beachfront sounds resembling howling wolves, distant but distinct, and reminiscent of a frightful night back in 1914 when his entire village had been stirred by such sounds; when the villagers awoke they discovered that the azure water of their lake had turned a murky red.

It was a mournful precursor of things to come, my father explained to my mother: his own father would soon die unexpectedly of an undiagnosed ailment, and a bloody world war would destroy the lives of so many of his young countrymen, including his older brother.

I, too, had sometimes heard in Ocean City at night what sounded like wolves echoing above the sand dunes; but I knew they were really stray dogs, part of the large population of underfed pets and watchdogs abandoned each fall by summer merchants and vacationers during the peak years of the Depression, when the local animal shelter was inadequately staffed or closed entirely.

Even in summertime the dogs roamed freely on the boardwalk during the Depression, mingling with the reduced number of tourists who strolled casually up and down the promenade, passing the restaurants of mostly unoccupied tables, the soundless bandstand outside the music pavilion, and the carousel’s riderless wooden horses.

My mother loathed the sight and smell of these dogs; and as if her disapproval provoked their spiteful nature, they followed her everywhere. Moments after she had emerged from the house to escort me to school before her mile walk along deserted streets to join my father at the store, the dogs would appear from behind fences and high-weeded yards and trail her by several paces in a quiet trot, softly whimpering and whining, or growling or panting with their tongues extended.

While there were a few pointers and terriers, spaniels and beagles, they were mostly mongrels of every breed and color, and all of them seemed unintimidated by my mother, even after she abruptly turned and glared at them and tried to drive them away with a sweeping gesture of her right arm in the air. They never attacked her or advanced close enough to nip at her high heels; it was mainly a game of territorial imperative that they played each morning with her. By the winter of 1940, the dogs had definitely won.

At this time my mother was caring for her second and final child, a daughter four years my junior; and I think that the daily responsibility of rearing two children, assisting in the store, and being followed, even when we children accompanied her, by the ragged retinue of dogs—a few of which often paused to copulate in the street as my sister and I watched in startled wonderment—drove my mother to ask my father to sell our house on the isolated north end of the island and move us into the more populated center of town.

This he unhesitatingly did, although in the depressed real estate market of that time he was forced to sell at an unfavorable price. But he also benefitted from these conditions by obtaining at a bargain on the main street of Ocean City a large brick building that had been the offices of a weekly newspaper lately absorbed in a merger. The spacious first floor of the building, with its high ceiling and balcony, its thick walls and deep interior, its annex and parking lot, provided more than enough room for my father’s various enterprises—his dress shop and dry-cleaning service, his fur storage vaults and tailoring trade.

More important to my mother, however, was the empty floor of the building, an open area as large as a dance hall that would be converted into an apartment offering her both a convenient closeness to my father and the option of distance from everyone else when she so desired. Since she also decorated this space in accord with her dictum that living quarters should be designed less to be lived in than to be looked at and admired, my sister and I soon found ourselves residing in an abode that was essentially an extended showroom. It was aglow with crystal chandeliers and sculpted candles in silver holders, and it had several bronze claw-footed marble-topped coffee tables surrounded by velvet sofas and chairs that bespoke comfort and taste but nonetheless conveyed the message that should we children ever take the liberty of reclining on their cushions and pillows, we should, upon rising, be certain we did not leave them rumpled or scattered or even at angles asymmetrical to the armrests.

Not only did my father not object to this fastidiously decorative ambience, he accentuated it by installing in the apartment several large mirrors that doubled the impression of almost everything in view, and also concealed in the rear of the apartment the existence of three ersatz bedrooms that for some reason my parents preferred not to acknowledge.

Each bed was separately enclosed within an L-shaped ten-foot-high partition that on the inside was backed by shelves and closets and on the outside was covered entirely with mirrors. Whatever was gained by this arrangement was lost whenever a visitor bumped into a mirror. And while I never remember at night being an unwitting monitor of my parents’ intimacy, I do know that otherwise in this domestic hall of mirrors we as a family hardly ever lost sight of one another.

Most embarrassing to me were those moments when, on entering the apartment unannounced after school, I saw reflected in a mirror, opposite a small alcove, the bowed head of my father as he knelt on the red velvet of a prie-dieu in front of a wall portrait of a bearded, brown-robed medieval monk. The monk’s face was emaciated, his lips seemed dry, and as he stood on a rock in sandals balancing a crosier in his right arm, his dark, somber eyes looked skyward as if seeking heavenly relief from the sins that surrounded him.

Ever since my earliest youth I had heard again and again my father’s astonishing tales about this fifteenth-century southern Italian miracle worker, Saint Francis of Paola. He had cured the crippled and revived the dead, he had multiplied food and levitated and with his hands stopped mountain boulders from rolling down upon villages; and one day in his hermitage, after an alluring young woman had tempted his celibacy, he had hastily retreated and leaped into an icy river to extinguish his passion.

The denial of pleasure, the rejection of worldly beauty and values, dominated the entire life of Saint Francis, my father had emphasized, adding that Francis as a boy had slept on stones in a cave near my father’s own village, had fasted and prayed and flagellated himself, and had finally established a credo of punishing piety and devotion that endures in southern Italy to this day, almost six hundred years after the birth of the saint.

I myself had seen other portraits of Saint Francis in the Philadelphia homes of some of my father’s Italian friends whom we occasionally visited on Sunday afternoons; and while I never openly doubted the veracity of Francis’s achievements, I never felt comfortable after I had climbed the many steps of the private staircase leading to the apartment and opened the living room door to see my father kneeling in prayer before this almost grotesque oil painting of a holy figure whose aura suggested agony and despair.

Prayer for me was either a private act witnessed exclusively by God or a public act carried out by the congregation or by me and my classmates in parochial school. It was not an act to be on exhibition in a family parlor in which I, as a nonparticipating observer, felt suddenly like an interloper, a trapped intruder in spiritual space, an awkward youth who dared not disturb my father’s meditation by announcing my presence. And yet I could not unobtrusively retreat from the room, or remain unaffected or even unafraid as I stood there, stifled against the wall, overhearing during these war years of the 1940s my father’s whispered words as he sought from Saint Francis nothing less than a miracle.

The beach in winter was dank and desolate, and the island dampened by the frigid spray of the ocean waves pounding relentlessly against the beachfront bulkheads, and the seaweed-covered beams beneath the white houses on the dunes creaked as quietly as the crabs crawling nearby.

The boardwalk that in summer was a festive promenade of suntanned couples and children’s balloons, of carousel tunes and colored lights spinning at night from the Ferris wheel, was occupied in winter by hundreds of sea gulls perched on the iron railings facing into the wind. When not resting they strutted outside the locked doors of vacated shops, or circled high in the sky, holding clams in their beaks that they soon dropped upon the boardwalk with a splattering cluck. Then they zoomed down and pounced on the exposed meat, pecking and pulling until there was nothing left but the jagged, salty white chips of empty shells.

By midwinter the shell-strewn promenade was a vast cemetery of clams, and from a distance the long elevated flat deck of the boardwalk resembled a stranded aircraft carrier being attacked by dive-bombers—and oddly juxtaposed in the fog behind the dunes loomed the rusting remains of a once sleek four-masted vessel that during a gale in the winter of 1901 had run aground on this small island in southern New Jersey called Ocean City.

The steel-hulled ship, flying a British flag and flaunting hundred-fifty-foot masts, had been sailing north along the New Jersey coast toward New York City, where it was scheduled to deliver one million dollars’ worth of Christmas cargo it had picked up five months before in Kobe, Japan. But during the middle of the night, while a number of crewmen drank rum and beer in a premature toast to the long journey’s end, a fierce storm rose and destroyed the ship’s sails, snapped its masts, and drove it into a sandbar within one hundred yards of the Ocean City boardwalk.

Awakened by the distress signals that flared in the night, the alarmed residents of Ocean City—a conservative community founded in 1879 by Methodist ministers and other Prohibitionists who wished to establish an island of abstinence and propriety—hastened to help the sailors, who were soon discovered to be battered but unharmed and smelling of sweat, salt water, and liquor.

After the entire thirty-three-man crew had been escorted to shore, they were sheltered and fed for days under the auspices of the town’s teetotaling elders and ministers’ wives; and while the sailors expressed gratitude for such hospitality they privately cursed their fate in being shipwrecked on an island so sedate and sober. But soon they were relocated by British nautical authorities, and the salvageable cargo was barged to New York to be sold at reduced prices. And the town returned to the tedium of winter.

The big ship, however, remained forever lodged in the soft white sand—unmovable, slowly sinking, a sight that served Ocean City’s pious guardians as a daily reminder of the grim consequences of intemperate guidance. But as I grew up in the late 1930s, more than three decades after the shipwreck—when the visible remnants at low tide consisted only of the barnacle-bitten ridge of the upper deck, the corroded brown rudder post and tiller, and a single lopsided mast—I viewed the vessel as a symbol of adventure and risk; and during my boyhood wanderings along the beach I became enchanted with exotic fantasies of nights in foreign ports, of braving the waves and wind with wayward men, and of escaping the rigid confines of this island on which I was born but never believed I belonged.

I saw myself always as an alien, an outsider, a drifter who, like the shipwrecked sailors, had arrived by accident. I felt different from my young friends in almost every way, different in the cut of my clothes, the food in my lunch box, the music I heard at home on the record player, the ideas and inner thoughts I revealed on those rare occasions when I was open and honest.

I was olive-skinned in a freckle-faced town, and I felt unrelated even to my parents, especially my father, who was indeed a foreigner—an unusual man in dress and manner, to whom I bore no physical resemblance and with whom I could never identify. Trim and elegant, with wavy dark hair and a small rust-colored moustache, he spoke English with an accent and received letters bearing strange-looking stamps.

These letters sometimes contained snapshots of soldiers wearing uniforms with insignia and epaulets unlike any I had seen on the recruit- ment posters displayed throughout the island. They were my uncles and cousins, my father explained to me quietly one day early in World War II, when I was ten; they were fighting in the Italian army, and—it was unnecessary for him to add—their enemy included the government of the United States.

I became increasingly sensitive to this fact when I sat through the newsreels each week at the local cinema; next to my unknowing classmates, I watched with private horror the destruction by Allied bombers of mountain villages and towns in southern Italy to which I was ancestrally linked through a historically ill-timed relationship with my Italian father. At any moment I half expected to see up on the screen, gazing down at me from a dust-covered United States Army truck filled with disheveled Italian prisoners being guarded at gunpoint, a sad face that I could identify from one of my father’s snapshots.

My father, on the other hand, seemed to share none of my confused sense of patriotism during the war years. He joined a citizens’ committee of shore patrolmen who kept watch along the waterfront at night, standing with binoculars on the boardwalk under the stanchioned lights that on the ocean side were painted black as a precaution against discovery by enemy submarines.

He made headlines in the local newspaper after a popular speech to the Rotary Club in which he reaffirmed his loyalty to the Allied cause, declaring that were he not too old for the draft (he was thirty-nine) he would proudly join the American troops at the front, in a uniform devotedly cut and stitched with his own hands.

Trained as an apprentice tailor in his native village, and later an assistant cutter in a prominent shop in Paris that employed an older Italian cousin, my father arrived in Ocean City circuitously and impulsively at the age of eighteen in 1922 with very little money, an extensive wardrobe, and the outward appearance of a man who knew exactly where he was going, when in fact nothing was further from the truth. He knew no one in town, barely knew the language, and yet, with a self-assurance that has always mystified me, he adjusted to this unusual island as readily as he could cut cloth to fit any size and shape.

Having noticed a “For Sale” sign in the window of a tailor shop in the center of town, my father approached the asthmatic owner, who was desperate to leave the island for the drier climate of Arizona. After a brief negotiation, my father acquired the business and thus began a lengthy, spirited campaign to bring the rakish fashion of the Continental boulevardier to the comparatively continent men of the south Jersey shore.

But after decorating his windows with lantern-jawed mannequins holding cigarettes and wearing Borsalino hats, and draping his counters with bolts of fine imported fabrics—and displaying on his walls such presumably persuasive regalia as his French master tailor’s diploma bordered by cherubim and a Greek goddess—my father made so few sales during his first year that he was finally forced to introduce into his shop a somewhat undignified gimmick called the Suit Club.

At the cost of one dollar per week, Suit Club members would print their names and addresses on small white cards and, after placing the cards in unmarked envelopes, would deposit them into a large opaque vase placed prominently atop a velvet-covered table next to a fashion photograph of a dapper man and woman posing with a greyhound on the greensward of an ornate country manor.

Each Friday evening just prior to closing time, my father would invite one of the assembled Suit Club members to close his eyes and pick from the vase a single envelope, which would reveal the name of the fortunate winner of a free suit, to be made from fabric selected by that individual; after two fittings, it would be ready for wearing within a week.

Since as many as three or four hundred people were soon paying a dollar each week to partake in this raffle, my father was earning on each free suit a profit perhaps three times the average cost of a custom-made suit in those days—to say nothing of the additional money he earned when he enticed a male winner into purchasing an extra pair of matching trousers.

But my father’s bonanza was abruptly terminated one day in 1928, when an anonymous complaint sent to City Hall, possibly by a rival tailor, charged that the Suit Club was a form of gambling clearly outlawed under the town charter; thus ended for all time my father’s full-time commitment to the reputable but precarious life of an artist with a needle and thread. My father did not climb down from an impoverished mountain in southern Italy and forsake the glorious lights of Paris and sail thousands of miles to the more opportunistic shores of America to end up as a poor tailor in Ocean City, New Jersey.

So he diversified. Advertising himself as a ladies’ furrier who could alter or remodel old coats as well as provide resplendent new ones (which he obtained on consignment from a Russian Jewish immigrant who resided in nearby Atlantic City), my father expanded his store to accommodate a refrigerated fur storage vault and extended the rear of the building to include a dry-cleaning plant overseen by a black Baptist deacon who during Prohibition operated a small side business in bootlegging. Later, in the 1930s, my father added a ladies’ dress boutique, having as partner and wife a well-tailored woman who once worked as a buyer in a large department store in Brooklyn.

He met her while attending an Italian wedding in that borough in December 1927. She was a bridesmaid, a graceful and slender woman of twenty with dark eyes and fair complexion and a style my father immediately recognized as both feminine and prepossessing. After a few dances at the reception under the scrutiny of her parents, and the frowns of the saxophone player in the band with whom she had recently gone out on a discreet double date, my father decided to delay his departure from Brooklyn for a day or two so that he might ingratiate himself with her. This he did with such panache that they were engaged within a year, and married six months later, after buying a small white house near the Ocean City beach, where, in the winter of 1932, I was born and awoke each morning to the smell of espresso and the roaring sound of the waves.

My first recollection of my mother was of a fashionable, solitary figure on the breezy boardwalk pushing a baby carriage with one hand while with the other stabilizing on her head a modish feathered hat at an unwavering angle against the will of the wind.

As I grew older I learned that she cared greatly about exactness in appearance, preciseness in fit, straightness in seams; and, except when positioned on a pedestal in the store as my father measured her for a new suit, she seemed to prefer standing at a distance from other people, conversing with customers over a counter, communicating with her friends via telephone rather than in person. On those infrequent occasions when her relatives from Brooklyn would visit us in Ocean City, I noticed how quickly she backed away from their touch after offering her cheek for a kiss of greeting. Once, during my preschool days as I accompanied her on an errand, I tried to hold on to her, to put my hand inside the pocket of her coat not only for the warmth but for a closer feeling with her presence. But when I tried this I felt her hand, gently but firmly, remove my own.

It was as if she were incapable of intimate contact with anyone but my father, whom she plainly adored to the exclusion of everyone else; and the impression persisted throughout my youth that I was a kind of orphan in the custody of a compatible couple whose way of life was strange and baffling.

One night at the dinner table when I casually picked up a loaf of Italian bread and placed it upside down in the basket, my father became furious and, without further explanation, turned the loaf right side up and demanded that I never repeat what I had done. Whenever we attended the cinema as a family we left before the end, possibly because of my parents’ inability or unwillingness to relate to the film’s content, be it drama or comedy. And although my parents spent their entire married life living along the sea, I never saw them go sailing, fishing, or swimming, and rarely did they even venture onto the beach itself.

In my mother’s case I suspect her avoidance of the beach was due to her desire to prevent the sun from scorching and darkening her fair skin. But I believe my father’s aversion to the sea was based on something deeper, more complex, somehow related to his boyhood in southern Italy. I suggest this because I often heard him refer to his region’s coastline as foreboding and malarial, a place of piracy and invasion; and as an avid reader of Greek mythology—his birthplace is not far from the renowned rock of Scylla, where the Homeric sea monster devoured sailors who had escaped the whirlpool of Charybdis—my father was prone to attaching chimerical significance to certain bizarre or inexplicable events that occurred during his youth along the streams and lakes below his village.

I remember overhearing, when I was eleven or twelve, my father complaining to my mother that he had just experienced a sleepless night during which he had been disturbed by beachfront sounds resembling howling wolves, distant but distinct, and reminiscent of a frightful night back in 1914 when his entire village had been stirred by such sounds; when the villagers awoke they discovered that the azure water of their lake had turned a murky red.

It was a mournful precursor of things to come, my father explained to my mother: his own father would soon die unexpectedly of an undiagnosed ailment, and a bloody world war would destroy the lives of so many of his young countrymen, including his older brother.

I, too, had sometimes heard in Ocean City at night what sounded like wolves echoing above the sand dunes; but I knew they were really stray dogs, part of the large population of underfed pets and watchdogs abandoned each fall by summer merchants and vacationers during the peak years of the Depression, when the local animal shelter was inadequately staffed or closed entirely.

Even in summertime the dogs roamed freely on the boardwalk during the Depression, mingling with the reduced number of tourists who strolled casually up and down the promenade, passing the restaurants of mostly unoccupied tables, the soundless bandstand outside the music pavilion, and the carousel’s riderless wooden horses.

My mother loathed the sight and smell of these dogs; and as if her disapproval provoked their spiteful nature, they followed her everywhere. Moments after she had emerged from the house to escort me to school before her mile walk along deserted streets to join my father at the store, the dogs would appear from behind fences and high-weeded yards and trail her by several paces in a quiet trot, softly whimpering and whining, or growling or panting with their tongues extended.

While there were a few pointers and terriers, spaniels and beagles, they were mostly mongrels of every breed and color, and all of them seemed unintimidated by my mother, even after she abruptly turned and glared at them and tried to drive them away with a sweeping gesture of her right arm in the air. They never attacked her or advanced close enough to nip at her high heels; it was mainly a game of territorial imperative that they played each morning with her. By the winter of 1940, the dogs had definitely won.

At this time my mother was caring for her second and final child, a daughter four years my junior; and I think that the daily responsibility of rearing two children, assisting in the store, and being followed, even when we children accompanied her, by the ragged retinue of dogs—a few of which often paused to copulate in the street as my sister and I watched in startled wonderment—drove my mother to ask my father to sell our house on the isolated north end of the island and move us into the more populated center of town.

This he unhesitatingly did, although in the depressed real estate market of that time he was forced to sell at an unfavorable price. But he also benefitted from these conditions by obtaining at a bargain on the main street of Ocean City a large brick building that had been the offices of a weekly newspaper lately absorbed in a merger. The spacious first floor of the building, with its high ceiling and balcony, its thick walls and deep interior, its annex and parking lot, provided more than enough room for my father’s various enterprises—his dress shop and dry-cleaning service, his fur storage vaults and tailoring trade.

More important to my mother, however, was the empty floor of the building, an open area as large as a dance hall that would be converted into an apartment offering her both a convenient closeness to my father and the option of distance from everyone else when she so desired. Since she also decorated this space in accord with her dictum that living quarters should be designed less to be lived in than to be looked at and admired, my sister and I soon found ourselves residing in an abode that was essentially an extended showroom. It was aglow with crystal chandeliers and sculpted candles in silver holders, and it had several bronze claw-footed marble-topped coffee tables surrounded by velvet sofas and chairs that bespoke comfort and taste but nonetheless conveyed the message that should we children ever take the liberty of reclining on their cushions and pillows, we should, upon rising, be certain we did not leave them rumpled or scattered or even at angles asymmetrical to the armrests.

Not only did my father not object to this fastidiously decorative ambience, he accentuated it by installing in the apartment several large mirrors that doubled the impression of almost everything in view, and also concealed in the rear of the apartment the existence of three ersatz bedrooms that for some reason my parents preferred not to acknowledge.

Each bed was separately enclosed within an L-shaped ten-foot-high partition that on the inside was backed by shelves and closets and on the outside was covered entirely with mirrors. Whatever was gained by this arrangement was lost whenever a visitor bumped into a mirror. And while I never remember at night being an unwitting monitor of my parents’ intimacy, I do know that otherwise in this domestic hall of mirrors we as a family hardly ever lost sight of one another.

Most embarrassing to me were those moments when, on entering the apartment unannounced after school, I saw reflected in a mirror, opposite a small alcove, the bowed head of my father as he knelt on the red velvet of a prie-dieu in front of a wall portrait of a bearded, brown-robed medieval monk. The monk’s face was emaciated, his lips seemed dry, and as he stood on a rock in sandals balancing a crosier in his right arm, his dark, somber eyes looked skyward as if seeking heavenly relief from the sins that surrounded him.

Ever since my earliest youth I had heard again and again my father’s astonishing tales about this fifteenth-century southern Italian miracle worker, Saint Francis of Paola. He had cured the crippled and revived the dead, he had multiplied food and levitated and with his hands stopped mountain boulders from rolling down upon villages; and one day in his hermitage, after an alluring young woman had tempted his celibacy, he had hastily retreated and leaped into an icy river to extinguish his passion.

The denial of pleasure, the rejection of worldly beauty and values, dominated the entire life of Saint Francis, my father had emphasized, adding that Francis as a boy had slept on stones in a cave near my father’s own village, had fasted and prayed and flagellated himself, and had finally established a credo of punishing piety and devotion that endures in southern Italy to this day, almost six hundred years after the birth of the saint.

I myself had seen other portraits of Saint Francis in the Philadelphia homes of some of my father’s Italian friends whom we occasionally visited on Sunday afternoons; and while I never openly doubted the veracity of Francis’s achievements, I never felt comfortable after I had climbed the many steps of the private staircase leading to the apartment and opened the living room door to see my father kneeling in prayer before this almost grotesque oil painting of a holy figure whose aura suggested agony and despair.

Prayer for me was either a private act witnessed exclusively by God or a public act carried out by the congregation or by me and my classmates in parochial school. It was not an act to be on exhibition in a family parlor in which I, as a nonparticipating observer, felt suddenly like an interloper, a trapped intruder in spiritual space, an awkward youth who dared not disturb my father’s meditation by announcing my presence. And yet I could not unobtrusively retreat from the room, or remain unaffected or even unafraid as I stood there, stifled against the wall, overhearing during these war years of the 1940s my father’s whispered words as he sought from Saint Francis nothing less than a miracle.

Notă biografică

Gay Talesewas a reporter forThe New York Timesfrom 1956 to 1965. Since then he has written for The New York Times, Esquire, The New Yorker, Harper's Magazine,and other national publications. He is the author of 13 books. He lives with his wife, Nan, in New York City.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

At last employing his prodigious storytelling gifts to tell the saga of his own family's emigration to America from Italy in the years preceding World War II, Talese shares the hope and sacrifice that took them from the familiarity of the old world into the mysteries and challenges of the new.

At last employing his prodigious storytelling gifts to tell the saga of his own family's emigration to America from Italy in the years preceding World War II, Talese shares the hope and sacrifice that took them from the familiarity of the old world into the mysteries and challenges of the new.