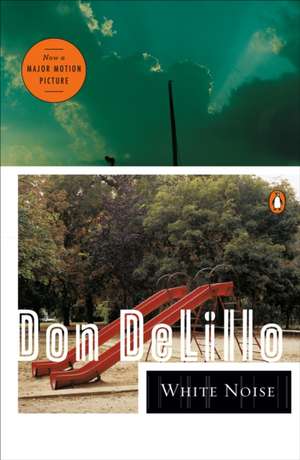

White Noise: Contemporary American Fiction

Autor Don DeLilloen Limba Engleză Paperback – 31 dec 1985 – vârsta de la 18 ani

Jack Gladney teaches Hitler studies at a liberal arts college in Middle America where his colleagues include New york expatriates who want to immerse themselves in "American magic and dread." Jack and his fourth wife, Babette, bound by their love, fear of death, and four ultramodern offspring, navigate the usual rocky passages of family life to the background babble of brand-name consumerism. Then a lethal black chemical cloud floats over their lives, an "airborne toxic event" unleashed by an industrial accident. The menacing cloud is a more urgent and visible version of the "white noise" engulfing the Gladney family--radio transmissions, sirens, microwaves, ultrasonic appliances, and TV murmerings--pulsing with life, yet heralding the danger of death.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 44.54 lei 3-5 săpt. | +30.85 lei 4-10 zile |

| Pan Macmillan – 17 feb 2022 | 44.54 lei 3-5 săpt. | +30.85 lei 4-10 zile |

| Penguin Books – 31 dec 1985 | 72.03 lei 3-5 săpt. | +9.51 lei 4-10 zile |

| Penguin Books – 30 noi 2009 | 101.88 lei 3-5 săpt. | +17.10 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 72.03 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 108

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.78€ • 14.39$ • 11.38£

13.78€ • 14.39$ • 11.38£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Livrare express 08-14 martie pentru 19.50 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780140077025

ISBN-10: 0140077022

Pagini: 326

Dimensiuni: 130 x 196 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Seria Contemporary American Fiction

ISBN-10: 0140077022

Pagini: 326

Dimensiuni: 130 x 196 x 16 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Penguin Books

Seria Contemporary American Fiction

Notă biografică

Don DeLillo published his first short story when he was twenty-three years old. He has since written twelve novels, including White Noise (1985) which won the National Book Award. It was followed by Libra (1988), his novel about the assassination of President Kennedy, and by Mao II, which won the PEN/Faulkner Award for Fiction. In 1997, he published the bestselling Underworld, and in 1999 he was awarded the Jerusalem Prize, given to a writer whose work expresses the theme of the freedom of the individual in society; he was the first American author to receive it. He is also a member of the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Descriere

Descriere de la o altă ediție sau format:

From a National Book Award-winning author comes this postmodern masterpiece. After a deadly toxic accident and his wife's addiction to an experimental drug, a man is forced to question everything about his life.

From a National Book Award-winning author comes this postmodern masterpiece. After a deadly toxic accident and his wife's addiction to an experimental drug, a man is forced to question everything about his life.

Recenzii

Extras

Introduction by Richard Powers ix

White Noise 1

Introduction

The Whiteness of the Noise

On a bright April morning thirty years ago, I stood on the balcony of my upper-story apartment in Somerville, Massachusetts, looking out on a plume full of ten thousand gallons of deadly phosphorus trichloride that rose hundreds of feet into the air, listening to the television spew a steady stream of dire speculation, and wondering whether to head in to work or call in sick. Five years later—just weeks after a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, released almost 100,000 pounds of methyl isocyanate into a densely populated area, killing many thousands of people—I picked up a just-published novel whose "airborne toxic event" triggered a broad spectrum of symptoms including heart palpitations and an intense feeling of déjà vu.

The publication of White Noise in 1985 placed Don DeLillo at the center of contemporary cultural imagination. I can think of few books written in my lifetime that have received such quick and wide acclaim while going on to exercise so deep an influence for decades thereafter. I can think of even fewer books more likely to remain essential guides to life in the Information Age, another quarter century on. As a result, like the book's "MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA," this relentlessly pored-over masterpiece of "American magic and dread" faces the risk of death by promotion to Classic. Yet even after twenty-five years, White Noise remains deeply disconcerting, prophetic, hilarious, volatile, enigmatic, and altogether resistant to containment or antidote. The world of Jack Gladney, his colleagues, and his family grows more estrangingly familiar, more recognizably alien with every subsequent cultural bewilderment.

The book's surface seductions are clear enough. Its dizzying kaleidoscope of genre parodies—domestic intrigue, Kmart realism, pulp disaster, psychological thriller, obsessive crime fiction, cycling nouveau roman—begins with a send-up of an academic novel and quickly plunges into dysfunctional family sitcom. From page one, DeLillo captures the drop-dead hysterical terror of the human cortex in full flight. Every thought, every traded commodity of tottering words passed between the members of this ad hoc family—Jack and Babette Gladney and their four "children by previous marriages," with walk-ons by half-sibs, wayward parents, and semi-ex spouses—teeters on the brink of dada. The makeshift Gladney clan raises its monument to unhinged information in a place somewhere between the Sunnis and the Moonies, Tennessee Ernie Williams and Sir Albert Einstein, a land where "forgetfulness has gotten into the air and water [and] entered the food chain."

No part of the Way We Think Now escapes skewering, and the Gladneys' demented family chatter—the torrent of "true, false, and other kinds of news"—threatens to pulp the mind of even the idle listener. Burlesque so merciless—the page-after-page pleasure of collective humiliation—could, all by itself, keep such a book thriving long after most of its coevals are on life support.

But DeLillo's mordant satire of the fissile and refused nuclear family serves only to launch his surprising care for these "fragile creatures surrounded by a world of hostile facts." In the overload of deranged Gladney babble, Jack marvels at the "colloquial density that makes family life the one medium of sense knowledge in which an astonishment of heart is routinely contained." And I marvel, too, on this late rereading, at a naked earnestness hiding inside a style that I years ago mistook for pure postmodern irony. Or rather, the marvel lies in that sound of human speech hungering for a time before irony and earnestness split into two strangers that deny their shared genes. What shocks me now is the book's terror-stricken tenderness. With whiplashing jump-cut between lampoon and compassion, DeLillo turns a hilarious domestic travesty into one of the great, unlikely family romances of the past hundred years. "Watching children sleep," Jack says, in a moment that peels contemporary cool back to its hottest core, "makes me feel devout, part of a spiritual system. It is the closest I can come to God."

Alongside that surprise warmth, the book's brutal accuracy has kept it current far beyond the moment when the best pure satire would have dated and staled. DeLillo's ear astounded me a quarter of a century ago; now it seems almost otherworldly in its resolution. On every other page, he's hearing the universe in all its subaudible frequencies. He retains everything; it's as if Borges's Funes, the man who forever remembers the slightest detail and minute change in angle, has taken a stroll around Anytown, USA, and retired to a cork-lined room to assemble the terabyte streams of waves and radiation into a panoramic survey. The inspired set-pieces of familial and academic babble read less like grotesque parodies than as exact replicas—the déjà vu symptoms of toxic residue, perfectly recorded simulations of waking dreams. We've all had those crazed conversations, all been bombarded by that exact static of shared inanity and never fully heard the soundtrack until DeLillo transcribed his high-gain recordings. Read the book, and you can't escape hearing all the old, overly familiar daily blare with new ears.

"I realized the place was awash in noise," Jack Gladney says of the supermarket, that pilgrim's chapel of the commodified world that cradles him like an innocent in the grip of a bipolar and raucous God.

The toneless systems, the jangle and skid of carts, the loudspeaker and coffee-making machines, the cries of children. And over it all, or under it all, a dull and unlocatable roar, as of some form of swarming life just outside the range of human apprehension.

But if the aisle is full of noise, it's also teeming with signals. Jack's colleague Murray serves up a paean to that same deafening supermarket:

This place recharges us spiritually, it prepares us, it's a gateway or pathway. Look how bright. It's full of psychic data…Everything is concealed in symbolism, hidden by veils of mystery and layers of cultural material…All the letters and numbers are here, all the colors of the spectrum, all the voices and sounds, all the code words and ceremonial phrases. It is just a question of deciphering, rearranging, peeling off the layers of unspeakability.

That same tone of Gnostic wonder infuses the book, weaving a counterpoint around the Gladneys' unshakable fear of death. Wonder and fear: the two incommensurate human emotions strike and collide, throwing off sparks that might equally well burn or warm. Secret messages float everywhere through the town of Blacksmith, filling the air with disembodied product names and ad copy liturgies. Jack's sleeping child—that closest approach to God—chants the now-famous shibboleth, Toyota Celica, two words that strike her listening father "like the name of an ancient power in the sky…a moment of splendid transcendence." How are we to take this startling pronouncement? Is it bleak, defeated mockery or genuine spiritual prayer? White Noise pushes down into a primal place, toward the parent impulse beneath both awe and terror. As Jack puts it, after the Airborne Toxic Event drives his family away from every former safety, "Our fear was accompanied by a sense of awe that bordered on the religious."

These pages are littered with such spiritual impulses. Throughout the book's three arched parts, dread and dread's send-ups sink Jack Gladney deeper toward life's central mystery. I'm struck, in reading a work that has become synonymous with grim postmodernism, one that so perfectly nails the Zeitgeist of the past-stripped present, by how often the book employs the word "ancient." DeLillo has described this novel as an attempt "to find a kind of radiance in dailiness. Sometimes this radiance can be almost frightening. Other times it can be almost holy or sacred." Yes, the book is a condemnation of somnambulist, consumerist co-optation, a savage look at the epileptic brainstorm induced by broadcast culture. But its full achievement may lie in its connection, underneath the litanies to Waffelos and Kabooms, with the long past. Something in co-opted consciousness is still stabbing away, trying to find forever.

Even the "narcotic undertow and eerie diseased brain-sucking power" of television is, according to Murray, filled with

coded messages and endless repetitions, like chants, like mantras. "Coke is it, Coke is it, Coke is it." The medium practically overflows with secret formulas if we can remember how to respond innocently and get past our irritation, weariness and disgust.

Maybe this cabalistic rapture is just more of DeLillo's academic burlesque, a death-rattle chuckle in the back of his throat as the billowing gas cloud rolls over us. Or maybe he puts forward Murray's hymn with all the sincerity of Saint Augustine. As with all great narrative art, White Noise suggests polarly opposed readings that nevertheless do not negate each other. For me, the book's brilliance lies not just in its castigation of commodity culture but in its portrait of the magic, cult religiosity that drives that culture—the brain's sacramental impulse to create all this stuff and noise in the first place. Only a short, blocked loop stands between consumption and consummation, between a chanted product name and the world's re-enchantment. Our tidal wave of toxic informentation means something, if only in revealing us. The landfills of escalating material miracles that we industriously amass form, in themselves, the most significant monument to our sickness unto death.

At the book's heart is the naked question: what to do with a fear of death that leaves every human action doomed and pathetic? The story's "routinely panic-stricken" cast chase after cures and take their evasive actions. Jack surveys all possible responses and resolutions to his death terror, but is satisfied by none. "Death is in the air," his friend Murray reassures him. "It is liberating suppressed material. It is getting us closer to things we haven't learned about ourselves." Well, perhaps. Jack isn't buying that particular offering, not entirely. But he does, in his panicked orbit, work his way to what may be the most mature available conclusion on the matter: "Fear is self-awareness raised to a higher level." Just that: awful, awe-inspiring, real-releasing fear. Death, the thing that we work so long and ingeniously to avoid, may or may not be the mother of all this beauty. But fear of death is the engine that renders "every word and thing a beadwork of bright creation."

In her own frantic attempt to evade the reach of the toxic cloud, Babette reasons with Jack's son Heinrich:

Every day on the news there's another toxic spill. Cancerous solvents from storage tanks, arsenic from smokestacks, radioactive water from power plants. How serious can it be if it happens all the time? Isn't the definition of a serious event based on the fact that it's not an everyday occurrence?

Folded inside her question is something close to the definition of DeLillo's art: we must learn to retrieve from the banal and quotidian the singular and cataclysmic.

White Noise, DeLillo's eighth novel, appeared at a whirlpool moment in the permanent turbulence between those two broad streams of American literature—call them telescopic and microscopic, the whaling ship and the carved scrimshaw. The book straddles the fantastic, maximalist experiments of the '60s and '70s and the stringent, intimate miniatures of the '80s and '90s, exploring the terrain between the two. In doing so, it has spawned an academic industry while still reducing pleasure-seeking readers to laugh-out-loud tears of recognition. Very few novels are both so deep and yet so fordable. White Noise makes a mockery of both "realism" and "surrealism" as terms descriptive of anything but their own sets of conventions, conventions that the twists of human need will always exceed. In fusing together inimical styles into something sui generis, DeLillo confirms J.B.S. Haldane's famous maxim: the everyday world is not just stranger than we suppose; it's stranger than we can suppose.

It's hard to think of a late-twentieth-century big theme that White Noise doesn't sound: the time-shared family, broadcast-addled consciousness, mediated violence, psychopharmaceutics, nascent biotech, information overload, runaway simulacra, terminal consumerism, eco-collapse, and the technological sublime. But how has the portrait aged over a quarter of a century? How much has the American mystery deepened? Since the book's publication, Bayh-Dole has turned even the College-on-the-Hill into one more market engine and patent-hungry profit center. Reality TV renders SIMUVAC's attempts to "use the real event in order to rehearse the simulation" almost sweetly nostalgic. The Internet—my God; imagine Heinrich editing Wikipedia, Jack writing a death blog, or Babette perusing offshoredrugs.com—has left us all drowning in so much spectacular sound and light that even eyes and ears as acute as DeLillo's must despair of rendering it. If you thought the world was awash in noise then, half a decade before the first Web browser, just put your ear to today's Twitter.

But the book has long since affixed itself dead center at the collision of everyday nonsense and ancient signals. Take any one of the hundreds of aphorisms that populate every chapter, and Google it. Say: "We still lead the world in stimuli." You'll get at least a cloud full of hits, often enough to fill the horizon.

In its search for the daily radiance inside our standing terror, White Noise has survived long beyond any reasonable use-by date. You might substitute SUVs for station wagons, add nanotech gray goo to the list of looming toxicities, info-dump some tables of stats on digital information sickness, spend a few nanoseconds describing YouTube, briefly cite the final destruction of attention by multitasking, reference the Institute for Paris Hiltonomics, and swap Homeland Security for SIMUVAC, but no conceivable updating of the book could better catch the torrent of late capitalism's wall of death-defying noise or the signs and wonders still pooling just behind it. The book has exercised profound influence on two generations of world novelists. It now has great-grandchildren, babbling away in all kinds of codes.

To read the book is to be awash in signals, unsure of what's profound and what's banal, what's asserted and what's denied. It's harder still to say what all the signals signify. "All plots tend to move deathward": another of Jack Gladney's aphorisms that now proliferate across thousands of the world's exploding blogs.

This is the nature of plots. Political plots, terrorist plots, lovers' plots, narrative plots, plots that are part of children's games. We edge nearer death every time we plot. It is like a contract that all must sign, the plotters as well as those who are the target of the plots.

In short, a family plot, from the Old English: a slice of ground. His friend, the monklike—or maybe Mephistophelean—Murray, insists on exactly the opposite: "To plot is to live." Plot as escape plan, from the Old French, for vital, secret schemes. Which will it be? Which plot has our name on it?

DeLillo's art, of course, hovers over the unresolvable divide. A good story, at its best, does much better than decide; it embodies. It contains in itself the very nub of being's contradictions. It catches us in the act of plotting, wherever plot might lead. White Noise mixes incommensurable modes of tenderness and burlesque, awe and despair that will neither cohere nor concede, modes as conflicted and concurrent as the simulating, dissimulating mind forever plotting to consume eternity and evade its own end.

Near the finish of this braided plot, astonished by a series of toxin-intensified, transcendental, postmodern sunsets, Jack is at a loss for exactly what he ought to feel:

[W]e don't know whether we are watching in wonder or dread, we don't know what we are watching or what it means, we don't know whether it is permanent, a level of experience to which we will gradually adjust, into which our uncertainty will eventually be absorbed, or just some atmospheric weirdness, soon to pass.

And at story's end, we, too, are left transfixed in the supermarket of Blacksmith, under the perpetual shadow of the Airborne Event, suspended between satire and sacred ritual, straddling the real and hyperreal, caught between dread and wonder, ill-equipped for knowing, dwarfed by the billowing cloud hanging perpetually on the horizon, but unwilling to give up even a day of our bewilderment.

The future always changes the past, and twenty-five years of constant upheaval should have sufficed to change both me and this book beyond recognition. But reading it again now, I feel much as I did as a young man first coming upon it—déjà vu all over again. I come out of the book feeling like the Gladneys' child Wilder, after his epic, superhuman, daylong crying jag:

it was as though he'd just returned from a period of wandering in some remote and holy place, in sand barrens or snowy ranges—a place where things are said, sights are seen, distances reached which we in our ordinary toil can only regard with the mingled reverence and wonder we hold in reserve for feats of the most sublime and difficult dimensions.

That place is as near and as foreign as speech. To get to that place—to reanimate words and free the dead souls inside them—DeLillo employs a brilliant palette of estrangement. The prose swells with weird, discontinuous wormholes of thought, chanted trademark trinities, exquisite abandoned corpses, sudden cut-ins, floating particles of voice, whatever comes after free indirect discourse, chains of causality and cross-purposed connection with random bits elided or dropped or injected suddenly from another train of thought. Every non sequitur and attention deficit articulates a little death. But through the narrative aporia and amnesiac gaps, words push forward, words as near-palpable things, and "things as facts and passions."

DeLillo's great theme is speech—its coded traces and intimations. In everything he writes, he's intent on laying bare what words enable and prevent. At every turn in White Noise, one or another of his characters mistakes the map for the place. Not surprisingly, the ultimate side-effect of Dylar—the drug designed to eliminate fear of death—is to turn words indistinguishable from the things they mention. His people scramble for words that might contain their fright; they seek out incantations and spells real enough to solidify their days and infuse their lives with sense. But life and death remain irreducibly strange, infolded processes that defy all the rationalizing of grammar. The force that words seek will not yield to meaning, yet it is still signal. It hides deep in the background hum, but never quite disperses into noise.

Another famous Haldane utterance: "I wish I had the voice of Homer to sing of rectal carcinoma." DeLillo, ventriloquizing through his terrified, rambling cast, comes close. "It's language," DeLillo has said, "the sheer pleasure of making it and bending it and seeing it form on the page and hearing it whistle in my head—this is the thing that makes my work go. And art can be exhilarating despite the darkness." Indeed, sometimes, in these pages, reader, writer, and characters alike make a mass jailbreak from the prison house of language and wind up in some beachside bungalow, where words turn almost better than comfort. "Is there something so innocent in the recitation of names," Jack wonders aloud, "that God is pleased?"

As prescient as the book was, twenty-five years ago, White Noise offers no particular prediction of life another quarter century in the future. We may stagger on, bathed in the waves and radiation of our splendid invention. We may extract from the noise some saving signal or transforming word. We may well cook ourselves, sitting paralyzed in the self-made, self-sealed pressure cooker, like the proverbial habituating frog until the atmosphere itself boils away. And on the pedestal of humanity's monument, these words may appear: "The bodies weren't in the places they would have been, in an actual simulation." Whatever our endlessly delayed real-life denouement, DeLillo's work remains that most cunning of planned mock-ups, the kind that, in representing, re-presents us, returns us to ourselves, to this moment, to our standing panasonic racket, only now without filters, briefly mindful again after long sleepwalking, and ears wide open to the sound that passes all understanding. As Jack discovers, even in the run-up to total nothingness, "There is just no end of surprise."

In one of their many urgent, noise-dulled, crosswise dialogues of dread, Jack and Babette compete to outbid each other in naming their fear of death. "What if death is nothing but sound?" she asks him, in her moment of maximum terror. Indeed: what then? "You hear it forever. Sound all around. How awful." And how full of awe. But until the day when we discover where the plot is dragging us, we're left here to listen to the awful hum, a grim and wildly funny and ancient and sometimes even sacred static at pitches beyond anyone's ability to shut out altogether: the radiance in dailiness, the language of waves and radiation, the sounds the dead use to speak to the living.

Richard Powers

Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from White Noise Copyright © Don Delillo, 2009.

White Noise 1

Introduction

The Whiteness of the Noise

On a bright April morning thirty years ago, I stood on the balcony of my upper-story apartment in Somerville, Massachusetts, looking out on a plume full of ten thousand gallons of deadly phosphorus trichloride that rose hundreds of feet into the air, listening to the television spew a steady stream of dire speculation, and wondering whether to head in to work or call in sick. Five years later—just weeks after a Union Carbide plant in Bhopal, India, released almost 100,000 pounds of methyl isocyanate into a densely populated area, killing many thousands of people—I picked up a just-published novel whose "airborne toxic event" triggered a broad spectrum of symptoms including heart palpitations and an intense feeling of déjà vu.

The publication of White Noise in 1985 placed Don DeLillo at the center of contemporary cultural imagination. I can think of few books written in my lifetime that have received such quick and wide acclaim while going on to exercise so deep an influence for decades thereafter. I can think of even fewer books more likely to remain essential guides to life in the Information Age, another quarter century on. As a result, like the book's "MOST PHOTOGRAPHED BARN IN AMERICA," this relentlessly pored-over masterpiece of "American magic and dread" faces the risk of death by promotion to Classic. Yet even after twenty-five years, White Noise remains deeply disconcerting, prophetic, hilarious, volatile, enigmatic, and altogether resistant to containment or antidote. The world of Jack Gladney, his colleagues, and his family grows more estrangingly familiar, more recognizably alien with every subsequent cultural bewilderment.

The book's surface seductions are clear enough. Its dizzying kaleidoscope of genre parodies—domestic intrigue, Kmart realism, pulp disaster, psychological thriller, obsessive crime fiction, cycling nouveau roman—begins with a send-up of an academic novel and quickly plunges into dysfunctional family sitcom. From page one, DeLillo captures the drop-dead hysterical terror of the human cortex in full flight. Every thought, every traded commodity of tottering words passed between the members of this ad hoc family—Jack and Babette Gladney and their four "children by previous marriages," with walk-ons by half-sibs, wayward parents, and semi-ex spouses—teeters on the brink of dada. The makeshift Gladney clan raises its monument to unhinged information in a place somewhere between the Sunnis and the Moonies, Tennessee Ernie Williams and Sir Albert Einstein, a land where "forgetfulness has gotten into the air and water [and] entered the food chain."

No part of the Way We Think Now escapes skewering, and the Gladneys' demented family chatter—the torrent of "true, false, and other kinds of news"—threatens to pulp the mind of even the idle listener. Burlesque so merciless—the page-after-page pleasure of collective humiliation—could, all by itself, keep such a book thriving long after most of its coevals are on life support.

But DeLillo's mordant satire of the fissile and refused nuclear family serves only to launch his surprising care for these "fragile creatures surrounded by a world of hostile facts." In the overload of deranged Gladney babble, Jack marvels at the "colloquial density that makes family life the one medium of sense knowledge in which an astonishment of heart is routinely contained." And I marvel, too, on this late rereading, at a naked earnestness hiding inside a style that I years ago mistook for pure postmodern irony. Or rather, the marvel lies in that sound of human speech hungering for a time before irony and earnestness split into two strangers that deny their shared genes. What shocks me now is the book's terror-stricken tenderness. With whiplashing jump-cut between lampoon and compassion, DeLillo turns a hilarious domestic travesty into one of the great, unlikely family romances of the past hundred years. "Watching children sleep," Jack says, in a moment that peels contemporary cool back to its hottest core, "makes me feel devout, part of a spiritual system. It is the closest I can come to God."

Alongside that surprise warmth, the book's brutal accuracy has kept it current far beyond the moment when the best pure satire would have dated and staled. DeLillo's ear astounded me a quarter of a century ago; now it seems almost otherworldly in its resolution. On every other page, he's hearing the universe in all its subaudible frequencies. He retains everything; it's as if Borges's Funes, the man who forever remembers the slightest detail and minute change in angle, has taken a stroll around Anytown, USA, and retired to a cork-lined room to assemble the terabyte streams of waves and radiation into a panoramic survey. The inspired set-pieces of familial and academic babble read less like grotesque parodies than as exact replicas—the déjà vu symptoms of toxic residue, perfectly recorded simulations of waking dreams. We've all had those crazed conversations, all been bombarded by that exact static of shared inanity and never fully heard the soundtrack until DeLillo transcribed his high-gain recordings. Read the book, and you can't escape hearing all the old, overly familiar daily blare with new ears.

"I realized the place was awash in noise," Jack Gladney says of the supermarket, that pilgrim's chapel of the commodified world that cradles him like an innocent in the grip of a bipolar and raucous God.

The toneless systems, the jangle and skid of carts, the loudspeaker and coffee-making machines, the cries of children. And over it all, or under it all, a dull and unlocatable roar, as of some form of swarming life just outside the range of human apprehension.

But if the aisle is full of noise, it's also teeming with signals. Jack's colleague Murray serves up a paean to that same deafening supermarket:

This place recharges us spiritually, it prepares us, it's a gateway or pathway. Look how bright. It's full of psychic data…Everything is concealed in symbolism, hidden by veils of mystery and layers of cultural material…All the letters and numbers are here, all the colors of the spectrum, all the voices and sounds, all the code words and ceremonial phrases. It is just a question of deciphering, rearranging, peeling off the layers of unspeakability.

That same tone of Gnostic wonder infuses the book, weaving a counterpoint around the Gladneys' unshakable fear of death. Wonder and fear: the two incommensurate human emotions strike and collide, throwing off sparks that might equally well burn or warm. Secret messages float everywhere through the town of Blacksmith, filling the air with disembodied product names and ad copy liturgies. Jack's sleeping child—that closest approach to God—chants the now-famous shibboleth, Toyota Celica, two words that strike her listening father "like the name of an ancient power in the sky…a moment of splendid transcendence." How are we to take this startling pronouncement? Is it bleak, defeated mockery or genuine spiritual prayer? White Noise pushes down into a primal place, toward the parent impulse beneath both awe and terror. As Jack puts it, after the Airborne Toxic Event drives his family away from every former safety, "Our fear was accompanied by a sense of awe that bordered on the religious."

These pages are littered with such spiritual impulses. Throughout the book's three arched parts, dread and dread's send-ups sink Jack Gladney deeper toward life's central mystery. I'm struck, in reading a work that has become synonymous with grim postmodernism, one that so perfectly nails the Zeitgeist of the past-stripped present, by how often the book employs the word "ancient." DeLillo has described this novel as an attempt "to find a kind of radiance in dailiness. Sometimes this radiance can be almost frightening. Other times it can be almost holy or sacred." Yes, the book is a condemnation of somnambulist, consumerist co-optation, a savage look at the epileptic brainstorm induced by broadcast culture. But its full achievement may lie in its connection, underneath the litanies to Waffelos and Kabooms, with the long past. Something in co-opted consciousness is still stabbing away, trying to find forever.

Even the "narcotic undertow and eerie diseased brain-sucking power" of television is, according to Murray, filled with

coded messages and endless repetitions, like chants, like mantras. "Coke is it, Coke is it, Coke is it." The medium practically overflows with secret formulas if we can remember how to respond innocently and get past our irritation, weariness and disgust.

Maybe this cabalistic rapture is just more of DeLillo's academic burlesque, a death-rattle chuckle in the back of his throat as the billowing gas cloud rolls over us. Or maybe he puts forward Murray's hymn with all the sincerity of Saint Augustine. As with all great narrative art, White Noise suggests polarly opposed readings that nevertheless do not negate each other. For me, the book's brilliance lies not just in its castigation of commodity culture but in its portrait of the magic, cult religiosity that drives that culture—the brain's sacramental impulse to create all this stuff and noise in the first place. Only a short, blocked loop stands between consumption and consummation, between a chanted product name and the world's re-enchantment. Our tidal wave of toxic informentation means something, if only in revealing us. The landfills of escalating material miracles that we industriously amass form, in themselves, the most significant monument to our sickness unto death.

At the book's heart is the naked question: what to do with a fear of death that leaves every human action doomed and pathetic? The story's "routinely panic-stricken" cast chase after cures and take their evasive actions. Jack surveys all possible responses and resolutions to his death terror, but is satisfied by none. "Death is in the air," his friend Murray reassures him. "It is liberating suppressed material. It is getting us closer to things we haven't learned about ourselves." Well, perhaps. Jack isn't buying that particular offering, not entirely. But he does, in his panicked orbit, work his way to what may be the most mature available conclusion on the matter: "Fear is self-awareness raised to a higher level." Just that: awful, awe-inspiring, real-releasing fear. Death, the thing that we work so long and ingeniously to avoid, may or may not be the mother of all this beauty. But fear of death is the engine that renders "every word and thing a beadwork of bright creation."

In her own frantic attempt to evade the reach of the toxic cloud, Babette reasons with Jack's son Heinrich:

Every day on the news there's another toxic spill. Cancerous solvents from storage tanks, arsenic from smokestacks, radioactive water from power plants. How serious can it be if it happens all the time? Isn't the definition of a serious event based on the fact that it's not an everyday occurrence?

Folded inside her question is something close to the definition of DeLillo's art: we must learn to retrieve from the banal and quotidian the singular and cataclysmic.

White Noise, DeLillo's eighth novel, appeared at a whirlpool moment in the permanent turbulence between those two broad streams of American literature—call them telescopic and microscopic, the whaling ship and the carved scrimshaw. The book straddles the fantastic, maximalist experiments of the '60s and '70s and the stringent, intimate miniatures of the '80s and '90s, exploring the terrain between the two. In doing so, it has spawned an academic industry while still reducing pleasure-seeking readers to laugh-out-loud tears of recognition. Very few novels are both so deep and yet so fordable. White Noise makes a mockery of both "realism" and "surrealism" as terms descriptive of anything but their own sets of conventions, conventions that the twists of human need will always exceed. In fusing together inimical styles into something sui generis, DeLillo confirms J.B.S. Haldane's famous maxim: the everyday world is not just stranger than we suppose; it's stranger than we can suppose.

It's hard to think of a late-twentieth-century big theme that White Noise doesn't sound: the time-shared family, broadcast-addled consciousness, mediated violence, psychopharmaceutics, nascent biotech, information overload, runaway simulacra, terminal consumerism, eco-collapse, and the technological sublime. But how has the portrait aged over a quarter of a century? How much has the American mystery deepened? Since the book's publication, Bayh-Dole has turned even the College-on-the-Hill into one more market engine and patent-hungry profit center. Reality TV renders SIMUVAC's attempts to "use the real event in order to rehearse the simulation" almost sweetly nostalgic. The Internet—my God; imagine Heinrich editing Wikipedia, Jack writing a death blog, or Babette perusing offshoredrugs.com—has left us all drowning in so much spectacular sound and light that even eyes and ears as acute as DeLillo's must despair of rendering it. If you thought the world was awash in noise then, half a decade before the first Web browser, just put your ear to today's Twitter.

But the book has long since affixed itself dead center at the collision of everyday nonsense and ancient signals. Take any one of the hundreds of aphorisms that populate every chapter, and Google it. Say: "We still lead the world in stimuli." You'll get at least a cloud full of hits, often enough to fill the horizon.

In its search for the daily radiance inside our standing terror, White Noise has survived long beyond any reasonable use-by date. You might substitute SUVs for station wagons, add nanotech gray goo to the list of looming toxicities, info-dump some tables of stats on digital information sickness, spend a few nanoseconds describing YouTube, briefly cite the final destruction of attention by multitasking, reference the Institute for Paris Hiltonomics, and swap Homeland Security for SIMUVAC, but no conceivable updating of the book could better catch the torrent of late capitalism's wall of death-defying noise or the signs and wonders still pooling just behind it. The book has exercised profound influence on two generations of world novelists. It now has great-grandchildren, babbling away in all kinds of codes.

To read the book is to be awash in signals, unsure of what's profound and what's banal, what's asserted and what's denied. It's harder still to say what all the signals signify. "All plots tend to move deathward": another of Jack Gladney's aphorisms that now proliferate across thousands of the world's exploding blogs.

This is the nature of plots. Political plots, terrorist plots, lovers' plots, narrative plots, plots that are part of children's games. We edge nearer death every time we plot. It is like a contract that all must sign, the plotters as well as those who are the target of the plots.

In short, a family plot, from the Old English: a slice of ground. His friend, the monklike—or maybe Mephistophelean—Murray, insists on exactly the opposite: "To plot is to live." Plot as escape plan, from the Old French, for vital, secret schemes. Which will it be? Which plot has our name on it?

DeLillo's art, of course, hovers over the unresolvable divide. A good story, at its best, does much better than decide; it embodies. It contains in itself the very nub of being's contradictions. It catches us in the act of plotting, wherever plot might lead. White Noise mixes incommensurable modes of tenderness and burlesque, awe and despair that will neither cohere nor concede, modes as conflicted and concurrent as the simulating, dissimulating mind forever plotting to consume eternity and evade its own end.

Near the finish of this braided plot, astonished by a series of toxin-intensified, transcendental, postmodern sunsets, Jack is at a loss for exactly what he ought to feel:

[W]e don't know whether we are watching in wonder or dread, we don't know what we are watching or what it means, we don't know whether it is permanent, a level of experience to which we will gradually adjust, into which our uncertainty will eventually be absorbed, or just some atmospheric weirdness, soon to pass.

And at story's end, we, too, are left transfixed in the supermarket of Blacksmith, under the perpetual shadow of the Airborne Event, suspended between satire and sacred ritual, straddling the real and hyperreal, caught between dread and wonder, ill-equipped for knowing, dwarfed by the billowing cloud hanging perpetually on the horizon, but unwilling to give up even a day of our bewilderment.

The future always changes the past, and twenty-five years of constant upheaval should have sufficed to change both me and this book beyond recognition. But reading it again now, I feel much as I did as a young man first coming upon it—déjà vu all over again. I come out of the book feeling like the Gladneys' child Wilder, after his epic, superhuman, daylong crying jag:

it was as though he'd just returned from a period of wandering in some remote and holy place, in sand barrens or snowy ranges—a place where things are said, sights are seen, distances reached which we in our ordinary toil can only regard with the mingled reverence and wonder we hold in reserve for feats of the most sublime and difficult dimensions.

That place is as near and as foreign as speech. To get to that place—to reanimate words and free the dead souls inside them—DeLillo employs a brilliant palette of estrangement. The prose swells with weird, discontinuous wormholes of thought, chanted trademark trinities, exquisite abandoned corpses, sudden cut-ins, floating particles of voice, whatever comes after free indirect discourse, chains of causality and cross-purposed connection with random bits elided or dropped or injected suddenly from another train of thought. Every non sequitur and attention deficit articulates a little death. But through the narrative aporia and amnesiac gaps, words push forward, words as near-palpable things, and "things as facts and passions."

DeLillo's great theme is speech—its coded traces and intimations. In everything he writes, he's intent on laying bare what words enable and prevent. At every turn in White Noise, one or another of his characters mistakes the map for the place. Not surprisingly, the ultimate side-effect of Dylar—the drug designed to eliminate fear of death—is to turn words indistinguishable from the things they mention. His people scramble for words that might contain their fright; they seek out incantations and spells real enough to solidify their days and infuse their lives with sense. But life and death remain irreducibly strange, infolded processes that defy all the rationalizing of grammar. The force that words seek will not yield to meaning, yet it is still signal. It hides deep in the background hum, but never quite disperses into noise.

Another famous Haldane utterance: "I wish I had the voice of Homer to sing of rectal carcinoma." DeLillo, ventriloquizing through his terrified, rambling cast, comes close. "It's language," DeLillo has said, "the sheer pleasure of making it and bending it and seeing it form on the page and hearing it whistle in my head—this is the thing that makes my work go. And art can be exhilarating despite the darkness." Indeed, sometimes, in these pages, reader, writer, and characters alike make a mass jailbreak from the prison house of language and wind up in some beachside bungalow, where words turn almost better than comfort. "Is there something so innocent in the recitation of names," Jack wonders aloud, "that God is pleased?"

As prescient as the book was, twenty-five years ago, White Noise offers no particular prediction of life another quarter century in the future. We may stagger on, bathed in the waves and radiation of our splendid invention. We may extract from the noise some saving signal or transforming word. We may well cook ourselves, sitting paralyzed in the self-made, self-sealed pressure cooker, like the proverbial habituating frog until the atmosphere itself boils away. And on the pedestal of humanity's monument, these words may appear: "The bodies weren't in the places they would have been, in an actual simulation." Whatever our endlessly delayed real-life denouement, DeLillo's work remains that most cunning of planned mock-ups, the kind that, in representing, re-presents us, returns us to ourselves, to this moment, to our standing panasonic racket, only now without filters, briefly mindful again after long sleepwalking, and ears wide open to the sound that passes all understanding. As Jack discovers, even in the run-up to total nothingness, "There is just no end of surprise."

In one of their many urgent, noise-dulled, crosswise dialogues of dread, Jack and Babette compete to outbid each other in naming their fear of death. "What if death is nothing but sound?" she asks him, in her moment of maximum terror. Indeed: what then? "You hear it forever. Sound all around. How awful." And how full of awe. But until the day when we discover where the plot is dragging us, we're left here to listen to the awful hum, a grim and wildly funny and ancient and sometimes even sacred static at pitches beyond anyone's ability to shut out altogether: the radiance in dailiness, the language of waves and radiation, the sounds the dead use to speak to the living.

Richard Powers

Reprinted by arrangement with Penguin Group (USA) Inc., from White Noise Copyright © Don Delillo, 2009.