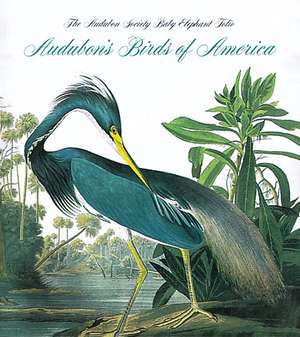

Audubon's Birds Of America: The National Audubon Society Baby Elephant Folio: Tiny Folio

Autor Roger Tory Petersonen Limba Engleză Hardback – 31 mar 2005

All Audubon's brilliant bird engravings come alive in one complete package!

This sparkling Tiny Folio™ edition of Audubon's Birds of America displays all 435 of Audubon's hand–colored engravings, graced with an illuminating introduction by Roger Tory Peterson that places Audubon in his ornithological and art historical context. Issued with the full endorsement and cooperation of the Audubon Society, the stunning Baby Elephant Folio—here reproduced in a miniature, gem–like version—was the first work ever to arrange Audubon's plates in scientific order.

This sparkling Tiny Folio™ edition of Audubon's Birds of America displays all 435 of Audubon's hand–colored engravings, graced with an illuminating introduction by Roger Tory Peterson that places Audubon in his ornithological and art historical context. Issued with the full endorsement and cooperation of the Audubon Society, the stunning Baby Elephant Folio—here reproduced in a miniature, gem–like version—was the first work ever to arrange Audubon's plates in scientific order.

Din seria Tiny Folio

-

Preț: 74.82 lei

Preț: 74.82 lei - 11%

Preț: 379.29 lei

Preț: 379.29 lei -

Preț: 68.68 lei

Preț: 68.68 lei -

Preț: 75.01 lei

Preț: 75.01 lei -

Preț: 75.01 lei

Preț: 75.01 lei -

Preț: 75.88 lei

Preț: 75.88 lei -

Preț: 75.64 lei

Preț: 75.64 lei -

Preț: 68.93 lei

Preț: 68.93 lei -

Preț: 68.99 lei

Preț: 68.99 lei -

Preț: 68.73 lei

Preț: 68.73 lei -

Preț: 77.11 lei

Preț: 77.11 lei -

Preț: 68.78 lei

Preț: 68.78 lei -

Preț: 61.76 lei

Preț: 61.76 lei -

Preț: 62.83 lei

Preț: 62.83 lei -

Preț: 66.78 lei

Preț: 66.78 lei -

Preț: 69.05 lei

Preț: 69.05 lei - 19%

Preț: 28.20 lei

Preț: 28.20 lei -

Preț: 59.55 lei

Preț: 59.55 lei -

Preț: 68.46 lei

Preț: 68.46 lei - 20%

Preț: 55.20 lei

Preț: 55.20 lei - 24%

Preț: 50.75 lei

Preț: 50.75 lei - 21%

Preț: 53.59 lei

Preț: 53.59 lei - 20%

Preț: 55.20 lei

Preț: 55.20 lei - 6%

Preț: 65.00 lei

Preț: 65.00 lei -

Preț: 68.84 lei

Preț: 68.84 lei

Preț: 57.06 lei

Preț vechi: 70.21 lei

-19% Nou

Puncte Express: 86

Preț estimativ în valută:

10.92€ • 11.86$ • 9.17£

10.92€ • 11.86$ • 9.17£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780789208149

ISBN-10: 0789208148

Pagini: 435

Ilustrații: 435ill.435col.ill.

Dimensiuni: 112 x 119 x 39 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Tiny Folio

Locul publicării:United States

ISBN-10: 0789208148

Pagini: 435

Ilustrații: 435ill.435col.ill.

Dimensiuni: 112 x 119 x 39 mm

Greutate: 0.41 kg

Editura: Abbeville Publishing Group

Colecția Abbeville Press

Seria Tiny Folio

Locul publicării:United States

Cuprins

Table of Contents from: Audubon's Birds of America

I Divers of Lakes and Bays, Wanderers of Seas and Coasts

II Waterfowl

III Scavengers and Birds of Prey

IV Upland Gamebirds and Marsh-dwellers

V Shorebirds

VI Seabirds

VII Showy Birds, Nocturnal Hunters, and Superb Aerialists

VIII Gleaners of Forest and Meadow

IX Songsters and Mimics

X Woodland Sprites

XI Flockers and Songbirds

I Divers of Lakes and Bays, Wanderers of Seas and Coasts

II Waterfowl

III Scavengers and Birds of Prey

IV Upland Gamebirds and Marsh-dwellers

V Shorebirds

VI Seabirds

VII Showy Birds, Nocturnal Hunters, and Superb Aerialists

VIII Gleaners of Forest and Meadow

IX Songsters and Mimics

X Woodland Sprites

XI Flockers and Songbirds

Recenzii

"A brilliant achievement." — The New York Times

Notă biografică

Roger Tory Peterson was widely regarded as America's most notable ornithologist from his historic publication of A Field Guide to the Birds in 1934 to his death in 1996.

Virginia Marie Peterson is a scientist and an expert on the environmental effects of oil spills.

Virginia Marie Peterson is a scientist and an expert on the environmental effects of oil spills.

Extras

Excerpt from: Audubon's Birds of America

Introduction

The Audubon Ethic

Like many another genius, John James Audubon was "the right man in the right place at the right time." He came to America with a fresh eye when it was still possible to document some of our unspoiled wilderness. He was also, during his lifetime, witness to the rapid changes that were taking place. Audubon’s real contribution was not the conservation ethic but awareness. That in itself is enough; awareness inevitably leads to concern.

Audubon’s frequent references to the palatability of birds and their availability in the market make us realize how far we have come in bird protection, if not in our epicurean tastes. He wrote that "the Barred Owl was very often exposed for sale in the New Orleans market; the Creoles make Gumbo of it, and pronounce the flesh palatable." Not only does he speak with a gourmets authority about the edibility of owls, loons, cormorants, and crows, but also the gustatory delights of juncos, white–throated sparrows, and robins.

It may seem paradoxical that this prototype of the woodsman–huntsman should have become the father figure of the conservation movement in North America. Like most other pioneer ornithologists, he was literally "in blood up to his elbows." He seemed obsessed with shooting; far more birds fell to his gun than he needed for drawing or research or for food. He once said that it was not a really good day unless he shot a hundred birds. But in his later writings, when recounting old shooting forays, there is a note of regret, as though his conscience were bothering him about the excesses of his trigger–happy days. He deplored the slaughter, especially when perpetrated by others—a double standard, if you will. But only once did he ask forgiveness for his acts. After describing the carnage that took place in the Florida Keys when he and his party landed in a colony of cormorants, "committing frightful havoc among them," he wrote: "You must try to excuse these murders, which in truth might not have been so numerous had I not thought of you [the reader] quite as often while on the Florida Keys, with the burning sun over my head and my body oozing at every pore, as I do now while peaceably scratching my paper with an iron pen, in one of the comfortable and quite cool houses of Old Scotland."

Repeatedly in his writings he reveals this dual nature, or inner conflict. After finding the nest of a pair of least sandpipers he wrote, "I was truly sorry to rob them of their eggs, although impelled to do so by the love of science, which offers a convenient excuse for even worse acts." Again, when he first met the arctic tern in the Magdalene Islands: "As I admired its easy and graceful motions, I felt agitated with a desire to possess it. Our guns were accordingly charged with mustard–seed shot, and one after another you might have seen the gentle birds come whirling down upon the waters…Alas, poor things! How well do I remember the pain it gave me, to be thus obliged to pass and execute sentence upon them. At that very moment I thought of those long past times when individuals of my own species were similarly treated; but I excused myself with plea of necessity, as I recharged my double gun." Another example of Audubon’s compulsion to shoot.

In light of his record it would seem inappropriate that one of the foremost conservation organizations in the United States should adopt Audubon’s name, but not so. He was ahead of his time. Like so many thoughtful sportsmen since, he eventually developed a conservation conscience. In an era when there were no game laws, no national parks or refuges, when there was no environmental ethic, when vulnerable nature gave way to human pressures and often sheer stupidity, he was a witness who sounded the alarm. He became more and more concerned during his later travels when, with the perspective of his years, he could see the trend. He noticed that prairie chickens, wild turkeys, Carolina parakeets, and many other birds were no longer as numerous as he once knew them. He wrote vividly and passionately about what he saw. He pondered the future, and some of the passages in his writing were prophetic.

Audubon could not have known that because of his artistry and his writing his name would become a household word, synonymous with birds, wildlife, and conservation. The National Audubon Society, formerly known as the National Association of Audubon Societies, was launched in the early years of this century, when no one spoke of "ecology" or "environment." It was primarily a bird organization at first. Over the years the Society has gone through a philosophical metamorphosis. Bird-watching was the precursor of ecological awareness, and "Audubon" has become a symbol of the environmental movement.

John James Audubon received high honors during the two decades prior to his death in 1851, but his greatest fame came in the century that followed. He had sparked a latent nationwide interest in the natural world, especially its birds, and his name became enshrined in hundreds of streets, towns, and parks across the land. Even a mountain peak in the Rockies is named in his honor. In the section of New York City where he lived there is an Audubon Avenue, an Audubon Theatre, and, now translated into digits, an Audubon telephone exchange. There was even a group that called themselves the "Audubon Artists," although they did not draw birds. But the greatest monument to his name is the National Audubon Society, which, unlike the "Audubon gun clubs" before the turn of the century, reflects the other side of John James Audubon, the passionate concern for the survival of wildlife and wild America that he developed as he grew older.

The Audubon Saga

The saga of Audubon has been told many times, with variations. It is not exactly a Horatio Alger tale of rags to riches, because the fledgling Audubon, born out of wedlock, was given a young gentleman’s tutoring and was all but spoiled by an indulgent stepmother.

Jean Jacques Fougère Audubon was born in 1785 on the island of Santo Domingo, now Haiti, in the West Indies. He was the son of an enterprising French sea captain who, after reverses in Les Cayes, where he owned property, returned to France with the boy. His mother was a young lady, Mademoiselle Rabin, originally from Nantes, who died before the captain returned to his home and legal wife in France. How he explained his transgressions to Madame Audubon is not known, but she took the four–year–old boy to her heart as her own as she did his sister, also born out of wedlock.

Perhaps to enable his son to escape conscription in Napoleon’s army, or perhaps to help him avoid the stigma of illegitimacy, Captain Audubon sent Jean Jacques at the age of eighteen to Mill Grove near Philadelphia where he owned property. The birds of America fascinated young Audubon, and drawing them became an obsession from which he never freed himself.

Audubon performed an experiment at Mill Grove that marked a "first" in the history of ornithology. He was fascinated by the phoebes that lived along the creek near his home. By placing silver threads about the legs of a brood of young phoebes to see whether they would return the following year, he became the first bird bander (or "ringer," to use the British term).

At Mill Grove Audubon married Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of a neighbor. Shortly thereafter the young couple moved westward to Louisville, Kentucky, where Jean Jacques’s father had set him up in business. But business was not in his blood, or so it seemed. It must be admitted that times were uncertain and investment risky on the frontier in those days. Moving farther west to the Mississippi and then down to New Orleans, Audubon met successive reverses until he was almost reduced to penury. Some called him impractical.

In reviewing this difficult period Audubon wrote, "Birds were then as now…I drew, I looked on nature only; my days were happy beyond human conception." He had conceived a grandiose plan of painting all the birds of North America—at least all then known—and at no time did he lose sight of this goal. He may have harbored the idea of eventual publication from the start, but it seems that the unheralded visit by pioneer ornithologist Alexander Wilson stirred his competitive spirit to action.

Audubon was often away from his family for months, exploring the wilderness, painting, and pursuing his dream. His devoted Lucy, who had borne him two sons, Victor and John, kept home and hearth together by teaching. He himself eked out a living as an itinerant portrait painter and as a dancing and fencing instructor.

As his portfolio bulged he began to look for a patron or a publisher, but he could find none in New York or Philadelphia. No one would risk the capital in those difficult days. Audubon decided that there might be a better chance of success in England, so with Lucy’s savings as a teacher and some money he had managed to acquire by painting portraits of well–to–do people, he set sail in 1826.

Abroad he was acclaimed immediately. Although he had been a nobody on his home turf, the rough, colorful man from the American frontier was a sensation abroad. He fascinated the genteel patrons of the art salons in London, Edinburgh, and Paris. Madison Avenue would have admired his public relations techniques. Long ahead of his time in the art of showmanship, he played his part well. To fit the image of the American woodsman, he wore buckskin and allowed his hair to grow long over his shoulders. The former bankrupt businessman became a super salesman, traveling from city to city to secure subscriptions. Meanwhile, as a sort of production manager, he monitored with infinite care the work of the engravers and a corps of colorists. He was not only artist, author, and scientist but also publisher, business manager, treasurer, and bill collector.

How could he have been "irresponsible" or "impractical" if he could do all this?

William Lizars of Edinburgh agreed to engrave and publish his work, but when only ten plates had been finished the colorists went on strike and Audubon was forced to find another engraver. This was Robert Havell, Jr., of London. Audubon was fortunate to be in the hands of such a skilled craftsman and artist. Havell’s accomplishment in etching the copper plates was as much a tour de force as the original paintings. It is instructive to compare the watercolors that hang in the galleries of the New York Historical Society to the Havell prints with which most of us are familiar.

In his 435 colorplates, Audubon depicted the birds exactly the size they were in life. Even the oversize format, 29 1/2 by 39 1/2 inches (known as "double–elephant folio"), the largest ever attempted up to then in the history of book publishing, was insufficient to accommodate the largest birds comfortably. Tall birds, such as the flamingo and the great blue heron, were fitted in by drooping their long necks toward their feet. On the other hand, tiny birds, such as kinglets and hummingbirds, are all but lost on the page.

Among the last few plates in the Elephant Folio and the 65 additional ones in the smaller octavo edition, Audubon included a number of birds from the western part of the country. These were his least successful efforts, probably because he had not seen these species in life.

Audubon as an Artist

Audubon implied that as a youth he had studied under the French master Jacques Louis David, and in doing so laid the foundation of his ability to draw. However, recent research has disputed this. Perhaps it was a good thing that his art was truly his own; like many another innovative genius he was not a clone of his professor. Nor were his paintings like the dull, documentary drawings of Alexander Wilson and his other contemporaries.

The thing that separated Audubon from his predecessors was that he was the first to give his birds the simulation of life. The others portrayed them stiffly and archaically as though they were on museum pedestals. To invest his birds with vitality and movement, Audubon worked from freshly killed specimens, wiring them into lifelike positions. In his youth he had tried hundreds of outline sketches but found it difficult to finish them. He fashioned a wooden model, "a tolerable-looking Dodo…I gave it a kick, broke it to atoms, walked off, and thought again." It was then that he conceived the procedure he was to follow for many years. He wrote: "One morning I leapt out of bed…went to the river, took a bath and returning to town inquired for wire of different sizes, bought some and was soon again at Mill Grove. I shot the first Kingfisher I met, pierced the body with wire, fixed it to the board, another wire held the head, smaller ones fixed the feet…There stood before me the real Kingfisher. I outlined the bird, colored it. This was my first drawing actually from nature."

It has been remarked that a Fuertes bird in repose has more the essence of the living bird than an Audubon bird vividly animated. This is understandable when one keeps in mind that Audubon wired up his specimens, and they sometimes looked it. In most cases this method worked fairly well, but the wild turkey cock, wired with its head looking over its back so as to fit the sheet, is almost a caricature. So are Audubon’s barred owl with the grinning squirrel and his two red–tailed hawks quarreling in mid–air for possession of a rabbit. His golden eagle frozen in flight with a hare, his two barn owls at night, and his squabbling caracaras are all too contrived. His two blue–winged teals look as though they were thrown through the air like footballs. Inasmuch as Audubon did not know some of the pelagic birds—the fulmar, greater shearwater, and tropic–bird—on their nesting ground, he showed them standing on their toes rather than resting on their bellies with their tarsi flat on the ground.

We can if we choose, be critical of these errors, but the wildlife artist of today is able to step on the shoulders of those who have gone before. In fairness, Audubon made the great leap forward at a time when most birds were drawn as though "stuffed" and fastened to wooden perches in museum cases. He took birds out of the glass case for all time and gave them a semblance of life. His paintings have a dramatic impact seldom equaled by those of his successors.

Louis Agassiz Fuertes, in a remarkable letter to his young protégé George Miksch Sutton, extolled Audubon’s strengths and defended his shortcomings, unaware that his "training under David" was apparently a myth.

"Say what you will of Audubon, he was the first and only man whose bird drawings showed the faintest hint of anatomical study, or that the fresh bird was in hand when the work was done, and is so immeasurably ahead of anything, up to his time or since, until the modern idea of drawing endlessly from life began to bear fruit, that its strength deserves all praise and honor, and its many weaknesses condonement, as they were the fruit of his training; stilted, tight, and unimaginative old [Jacques Louis] David sticks out in the stiff landscape, the hard outline, and the dull, lifeless shading, while the overpowering virility of Audubon is shown in the snappy, instantaneous attitudes, and dashing motion of his subjects. While theres much to criticize there is also much to learn, and much to admire, in studying the monumental classic that he left behind him. He made many errors, but he also left a living record that has been of inestimable value and stimulus to students, and made an everlasting mark in American ornithology. It is indeed hard to imagine what the science would be like in this country—and what the state of our bird world—had he not lived and wrought, and become a demigod to the ardent youth of the land." (From Bird Study, an Autobiography, by George Miksch Sutton, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980.)

Sutton, who himself later became a distinguished bird artist, wrote: "It was Audubon’s instinctive urge to dramatize which led him to represent so many of his birds in violent action. As several admirers of the great artist have pointed out, he was so surfeited with the conventional and lifeless poses used by the bird artists before him that he swung away from the traditional in a sort of furious huff…This was Audubon, lover of beauty, lover of the dramatic, avowed opponent of the prosy." If his art had been less startling and dramatic, it probably would not have survived and we would have heard little about Audubon, for relatively few people read his extensive writings.

Introduction

The Audubon Ethic

Like many another genius, John James Audubon was "the right man in the right place at the right time." He came to America with a fresh eye when it was still possible to document some of our unspoiled wilderness. He was also, during his lifetime, witness to the rapid changes that were taking place. Audubon’s real contribution was not the conservation ethic but awareness. That in itself is enough; awareness inevitably leads to concern.

Audubon’s frequent references to the palatability of birds and their availability in the market make us realize how far we have come in bird protection, if not in our epicurean tastes. He wrote that "the Barred Owl was very often exposed for sale in the New Orleans market; the Creoles make Gumbo of it, and pronounce the flesh palatable." Not only does he speak with a gourmets authority about the edibility of owls, loons, cormorants, and crows, but also the gustatory delights of juncos, white–throated sparrows, and robins.

It may seem paradoxical that this prototype of the woodsman–huntsman should have become the father figure of the conservation movement in North America. Like most other pioneer ornithologists, he was literally "in blood up to his elbows." He seemed obsessed with shooting; far more birds fell to his gun than he needed for drawing or research or for food. He once said that it was not a really good day unless he shot a hundred birds. But in his later writings, when recounting old shooting forays, there is a note of regret, as though his conscience were bothering him about the excesses of his trigger–happy days. He deplored the slaughter, especially when perpetrated by others—a double standard, if you will. But only once did he ask forgiveness for his acts. After describing the carnage that took place in the Florida Keys when he and his party landed in a colony of cormorants, "committing frightful havoc among them," he wrote: "You must try to excuse these murders, which in truth might not have been so numerous had I not thought of you [the reader] quite as often while on the Florida Keys, with the burning sun over my head and my body oozing at every pore, as I do now while peaceably scratching my paper with an iron pen, in one of the comfortable and quite cool houses of Old Scotland."

Repeatedly in his writings he reveals this dual nature, or inner conflict. After finding the nest of a pair of least sandpipers he wrote, "I was truly sorry to rob them of their eggs, although impelled to do so by the love of science, which offers a convenient excuse for even worse acts." Again, when he first met the arctic tern in the Magdalene Islands: "As I admired its easy and graceful motions, I felt agitated with a desire to possess it. Our guns were accordingly charged with mustard–seed shot, and one after another you might have seen the gentle birds come whirling down upon the waters…Alas, poor things! How well do I remember the pain it gave me, to be thus obliged to pass and execute sentence upon them. At that very moment I thought of those long past times when individuals of my own species were similarly treated; but I excused myself with plea of necessity, as I recharged my double gun." Another example of Audubon’s compulsion to shoot.

In light of his record it would seem inappropriate that one of the foremost conservation organizations in the United States should adopt Audubon’s name, but not so. He was ahead of his time. Like so many thoughtful sportsmen since, he eventually developed a conservation conscience. In an era when there were no game laws, no national parks or refuges, when there was no environmental ethic, when vulnerable nature gave way to human pressures and often sheer stupidity, he was a witness who sounded the alarm. He became more and more concerned during his later travels when, with the perspective of his years, he could see the trend. He noticed that prairie chickens, wild turkeys, Carolina parakeets, and many other birds were no longer as numerous as he once knew them. He wrote vividly and passionately about what he saw. He pondered the future, and some of the passages in his writing were prophetic.

Audubon could not have known that because of his artistry and his writing his name would become a household word, synonymous with birds, wildlife, and conservation. The National Audubon Society, formerly known as the National Association of Audubon Societies, was launched in the early years of this century, when no one spoke of "ecology" or "environment." It was primarily a bird organization at first. Over the years the Society has gone through a philosophical metamorphosis. Bird-watching was the precursor of ecological awareness, and "Audubon" has become a symbol of the environmental movement.

John James Audubon received high honors during the two decades prior to his death in 1851, but his greatest fame came in the century that followed. He had sparked a latent nationwide interest in the natural world, especially its birds, and his name became enshrined in hundreds of streets, towns, and parks across the land. Even a mountain peak in the Rockies is named in his honor. In the section of New York City where he lived there is an Audubon Avenue, an Audubon Theatre, and, now translated into digits, an Audubon telephone exchange. There was even a group that called themselves the "Audubon Artists," although they did not draw birds. But the greatest monument to his name is the National Audubon Society, which, unlike the "Audubon gun clubs" before the turn of the century, reflects the other side of John James Audubon, the passionate concern for the survival of wildlife and wild America that he developed as he grew older.

The Audubon Saga

The saga of Audubon has been told many times, with variations. It is not exactly a Horatio Alger tale of rags to riches, because the fledgling Audubon, born out of wedlock, was given a young gentleman’s tutoring and was all but spoiled by an indulgent stepmother.

Jean Jacques Fougère Audubon was born in 1785 on the island of Santo Domingo, now Haiti, in the West Indies. He was the son of an enterprising French sea captain who, after reverses in Les Cayes, where he owned property, returned to France with the boy. His mother was a young lady, Mademoiselle Rabin, originally from Nantes, who died before the captain returned to his home and legal wife in France. How he explained his transgressions to Madame Audubon is not known, but she took the four–year–old boy to her heart as her own as she did his sister, also born out of wedlock.

Perhaps to enable his son to escape conscription in Napoleon’s army, or perhaps to help him avoid the stigma of illegitimacy, Captain Audubon sent Jean Jacques at the age of eighteen to Mill Grove near Philadelphia where he owned property. The birds of America fascinated young Audubon, and drawing them became an obsession from which he never freed himself.

Audubon performed an experiment at Mill Grove that marked a "first" in the history of ornithology. He was fascinated by the phoebes that lived along the creek near his home. By placing silver threads about the legs of a brood of young phoebes to see whether they would return the following year, he became the first bird bander (or "ringer," to use the British term).

At Mill Grove Audubon married Lucy Bakewell, the daughter of a neighbor. Shortly thereafter the young couple moved westward to Louisville, Kentucky, where Jean Jacques’s father had set him up in business. But business was not in his blood, or so it seemed. It must be admitted that times were uncertain and investment risky on the frontier in those days. Moving farther west to the Mississippi and then down to New Orleans, Audubon met successive reverses until he was almost reduced to penury. Some called him impractical.

In reviewing this difficult period Audubon wrote, "Birds were then as now…I drew, I looked on nature only; my days were happy beyond human conception." He had conceived a grandiose plan of painting all the birds of North America—at least all then known—and at no time did he lose sight of this goal. He may have harbored the idea of eventual publication from the start, but it seems that the unheralded visit by pioneer ornithologist Alexander Wilson stirred his competitive spirit to action.

Audubon was often away from his family for months, exploring the wilderness, painting, and pursuing his dream. His devoted Lucy, who had borne him two sons, Victor and John, kept home and hearth together by teaching. He himself eked out a living as an itinerant portrait painter and as a dancing and fencing instructor.

As his portfolio bulged he began to look for a patron or a publisher, but he could find none in New York or Philadelphia. No one would risk the capital in those difficult days. Audubon decided that there might be a better chance of success in England, so with Lucy’s savings as a teacher and some money he had managed to acquire by painting portraits of well–to–do people, he set sail in 1826.

Abroad he was acclaimed immediately. Although he had been a nobody on his home turf, the rough, colorful man from the American frontier was a sensation abroad. He fascinated the genteel patrons of the art salons in London, Edinburgh, and Paris. Madison Avenue would have admired his public relations techniques. Long ahead of his time in the art of showmanship, he played his part well. To fit the image of the American woodsman, he wore buckskin and allowed his hair to grow long over his shoulders. The former bankrupt businessman became a super salesman, traveling from city to city to secure subscriptions. Meanwhile, as a sort of production manager, he monitored with infinite care the work of the engravers and a corps of colorists. He was not only artist, author, and scientist but also publisher, business manager, treasurer, and bill collector.

How could he have been "irresponsible" or "impractical" if he could do all this?

William Lizars of Edinburgh agreed to engrave and publish his work, but when only ten plates had been finished the colorists went on strike and Audubon was forced to find another engraver. This was Robert Havell, Jr., of London. Audubon was fortunate to be in the hands of such a skilled craftsman and artist. Havell’s accomplishment in etching the copper plates was as much a tour de force as the original paintings. It is instructive to compare the watercolors that hang in the galleries of the New York Historical Society to the Havell prints with which most of us are familiar.

In his 435 colorplates, Audubon depicted the birds exactly the size they were in life. Even the oversize format, 29 1/2 by 39 1/2 inches (known as "double–elephant folio"), the largest ever attempted up to then in the history of book publishing, was insufficient to accommodate the largest birds comfortably. Tall birds, such as the flamingo and the great blue heron, were fitted in by drooping their long necks toward their feet. On the other hand, tiny birds, such as kinglets and hummingbirds, are all but lost on the page.

Among the last few plates in the Elephant Folio and the 65 additional ones in the smaller octavo edition, Audubon included a number of birds from the western part of the country. These were his least successful efforts, probably because he had not seen these species in life.

Audubon as an Artist

Audubon implied that as a youth he had studied under the French master Jacques Louis David, and in doing so laid the foundation of his ability to draw. However, recent research has disputed this. Perhaps it was a good thing that his art was truly his own; like many another innovative genius he was not a clone of his professor. Nor were his paintings like the dull, documentary drawings of Alexander Wilson and his other contemporaries.

The thing that separated Audubon from his predecessors was that he was the first to give his birds the simulation of life. The others portrayed them stiffly and archaically as though they were on museum pedestals. To invest his birds with vitality and movement, Audubon worked from freshly killed specimens, wiring them into lifelike positions. In his youth he had tried hundreds of outline sketches but found it difficult to finish them. He fashioned a wooden model, "a tolerable-looking Dodo…I gave it a kick, broke it to atoms, walked off, and thought again." It was then that he conceived the procedure he was to follow for many years. He wrote: "One morning I leapt out of bed…went to the river, took a bath and returning to town inquired for wire of different sizes, bought some and was soon again at Mill Grove. I shot the first Kingfisher I met, pierced the body with wire, fixed it to the board, another wire held the head, smaller ones fixed the feet…There stood before me the real Kingfisher. I outlined the bird, colored it. This was my first drawing actually from nature."

It has been remarked that a Fuertes bird in repose has more the essence of the living bird than an Audubon bird vividly animated. This is understandable when one keeps in mind that Audubon wired up his specimens, and they sometimes looked it. In most cases this method worked fairly well, but the wild turkey cock, wired with its head looking over its back so as to fit the sheet, is almost a caricature. So are Audubon’s barred owl with the grinning squirrel and his two red–tailed hawks quarreling in mid–air for possession of a rabbit. His golden eagle frozen in flight with a hare, his two barn owls at night, and his squabbling caracaras are all too contrived. His two blue–winged teals look as though they were thrown through the air like footballs. Inasmuch as Audubon did not know some of the pelagic birds—the fulmar, greater shearwater, and tropic–bird—on their nesting ground, he showed them standing on their toes rather than resting on their bellies with their tarsi flat on the ground.

We can if we choose, be critical of these errors, but the wildlife artist of today is able to step on the shoulders of those who have gone before. In fairness, Audubon made the great leap forward at a time when most birds were drawn as though "stuffed" and fastened to wooden perches in museum cases. He took birds out of the glass case for all time and gave them a semblance of life. His paintings have a dramatic impact seldom equaled by those of his successors.

Louis Agassiz Fuertes, in a remarkable letter to his young protégé George Miksch Sutton, extolled Audubon’s strengths and defended his shortcomings, unaware that his "training under David" was apparently a myth.

"Say what you will of Audubon, he was the first and only man whose bird drawings showed the faintest hint of anatomical study, or that the fresh bird was in hand when the work was done, and is so immeasurably ahead of anything, up to his time or since, until the modern idea of drawing endlessly from life began to bear fruit, that its strength deserves all praise and honor, and its many weaknesses condonement, as they were the fruit of his training; stilted, tight, and unimaginative old [Jacques Louis] David sticks out in the stiff landscape, the hard outline, and the dull, lifeless shading, while the overpowering virility of Audubon is shown in the snappy, instantaneous attitudes, and dashing motion of his subjects. While theres much to criticize there is also much to learn, and much to admire, in studying the monumental classic that he left behind him. He made many errors, but he also left a living record that has been of inestimable value and stimulus to students, and made an everlasting mark in American ornithology. It is indeed hard to imagine what the science would be like in this country—and what the state of our bird world—had he not lived and wrought, and become a demigod to the ardent youth of the land." (From Bird Study, an Autobiography, by George Miksch Sutton, Austin: University of Texas Press, 1980.)

Sutton, who himself later became a distinguished bird artist, wrote: "It was Audubon’s instinctive urge to dramatize which led him to represent so many of his birds in violent action. As several admirers of the great artist have pointed out, he was so surfeited with the conventional and lifeless poses used by the bird artists before him that he swung away from the traditional in a sort of furious huff…This was Audubon, lover of beauty, lover of the dramatic, avowed opponent of the prosy." If his art had been less startling and dramatic, it probably would not have survived and we would have heard little about Audubon, for relatively few people read his extensive writings.

Descriere

All Audubon's brilliant bird engravings come alive in one complete package!

This sparkling Tiny Folio™ edition of Audubon's Birds of America displays all 435 of Audubon's hand–colored engravings, graced with an illuminating introduction by Roger Tory Peterson that places Audubon in his ornithological and art historical context. Issued with the full endorsement and cooperation of the Audubon Society, the stunning Baby Elephant Folio—here reproduced in a miniature, gem–like version—was the first work ever to arrange Audubon's plates in scientific order.

This sparkling Tiny Folio™ edition of Audubon's Birds of America displays all 435 of Audubon's hand–colored engravings, graced with an illuminating introduction by Roger Tory Peterson that places Audubon in his ornithological and art historical context. Issued with the full endorsement and cooperation of the Audubon Society, the stunning Baby Elephant Folio—here reproduced in a miniature, gem–like version—was the first work ever to arrange Audubon's plates in scientific order.