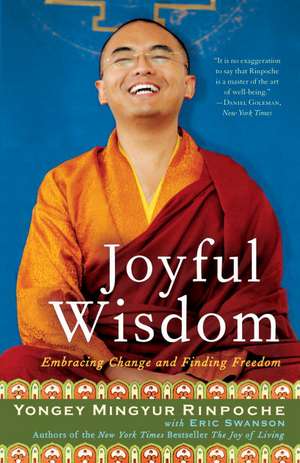

Joyful Wisdom: Embracing Change and Finding Freedom

Autor Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche Eric Swansonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 28 feb 2010

His new book, Joyful Wisdom, addresses the timely and timeless problem of anxiety in our everyday lives. “From the 2,500-year-old perspective of Buddhism,” Yongey Mingyur writes, “every chapter in human history could be described as an ‘age of anxiety.’ The anxiety we feel now has been part of the human condition for centuries.” So what do we do? Escape or succumb? Both routes inevitably lead to more complications and problems in our lives. “Buddhism,” he says, “offers a third option. We can look directly at the disturbing emotions and other problems we experience in our lives as stepping-stones to freedom. Instead of rejecting them or surrendering to them, we can befriend them, working through them to reach an enduring authentic experience of our inherent wisdom, confidence, clarity, and joy.”

Divided into three parts like a traditional Buddhist text, Joyful Wisdom identifies the sources of our unease, describes methods of meditation that enable us to transform our experience into deeper insight, and applies these methods to common emotional, physical, and personal problems. The result is a work at once wise, anecdotal, funny, informed, and graced with the author’s irresistible charm.

From the Hardcover edition.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (2) | 58.78 lei 26-32 zile | +21.50 lei 10-14 zile |

| Transworld Publishers Ltd – 4 mar 2010 | 58.78 lei 26-32 zile | +21.50 lei 10-14 zile |

| Three Rivers Press (CA) – 28 feb 2010 | 87.21 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 87.21 lei

Nou

16.69€ • 17.47$ • 13.81£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 0307407802

Pagini: 296

Dimensiuni: 135 x 202 x 17 mm

Greutate: 0.25 kg

Editura: Three Rivers Press (CA)

Notă biografică

Eric Swanson is coauthor of The Joy of Living. A graduate of Yale University and the Juilliard School, he is the author of the novels The Greenhouse Effect and The Boy in the Lake. After converting to Buddhism in 1995, he cowrote Karmapa, The Sacred Prophecy and authored What the Lotus Said, both of which focus on Buddhism within Tibet.

From the Hardcover edition.

Extras

The Light in the Tunnel

The sole purpose of human existence is to kindle a

light in the darkness of mere being.

--Carl Jung, Memories, Dreams, Reflections,

translated by Richard Winston and Clara Winston

SEVERAL YEARS AGO I found myself strapped inside an fMRI, a type of brain scanner that, to me, looked like a round, white coffin. I lay on a flat examination table that slid like a tongue inside the hollow cylinder which, I was told, held the scanning equipment. My arms, legs, and head were restrained so that it was nearly impossible to move, and a bite guard was inserted into my mouth to keep my jaws from moving. All the preparation--being strapped onto the table and so forth--was fairly interesting, since the technicians very courteously explained what they were doing and why. Even the sensation of being inserted into the machine was somewhat soothing, though I could see how someone with a very active imagination might feel as though he or she were being swallowed.

Inside the machine, however, it rapidly grew quite warm. Strapped in as I was, I couldn't wipe away any stray beads of sweat that crawled down my face. Scratching an itch was out of the question--and it's pretty amazing how itchy the body can get when there's not the slightest opportunity to scratch. The machine itself made a loud whirring noise like a siren.

Given these conditions, I suspect that spending an hour or so inside an fMRI scanner isn't something many people would choose to do. I'd volunteered, though, along with several other monks. Altogether, fifteen of us had agreed to undergo this uncomfortable experience as part of a neuroscientific study led by Professors Antoine Lutz and Richard Davidson at the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior in Madison, Wisconsin. The aim of the study was to examine the effects of long-term meditation practice on the brain. "Long-term" in this case meant somewhere between 10,000 and 50,000 hours of cumulative practice. For the younger volunteers, the hours had taken place over the course of perhaps fifteen years, while some of the older practitioners had been meditating for upwards of forty years.

As I understand it, an fMRI scanner is a bit different from a standard MRI, which employs powerful magnets and radio waves to produce--with the help of computers--a detailed still image of internal organs and body structures. While using the same magnet and radio wave technology, fMRI scanners provide a moment-by-moment record of changes in the brain's activity or function. The difference between the results of an MRI scan and the results of an fMRI scan is similar to the difference between a photograph and a video. Using fMRI technology, neuroscientists can track changes in various areas of the brain as subjects are asked to perform certain tasks--for example, listening to sounds, watching videos, or performing some sort of mental activity. Once the signals from the scanner are processed by a computer, the end result is a bit like a movie of the brain at work.

The tasks we were asked to perform involved alternating between certain meditation practices and just allowing our minds to rest in an ordinary or neutral state: three minutes of meditation followed by three minutes of resting. During the meditation periods we were treated to a number of sounds that could, by most standards, be described as quite unpleasant--for example, a woman screaming and a baby crying. One of the goals of the experiment was to determine what effect these disagreeable sounds had on the brains of experienced meditators. Would they interrupt the flow of concentrated attention? Would areas of the brain associated with irritation or anger become active? Perhaps there wouldn't be any effect at all.

In fact, the research team found that when these disturbing sounds were introduced, activity in areas of the brain associated with maternal love, empathy, and other positive mental states actually increased.1 Unpleasantness had triggered a deep state of calmness, clarity, and compassion.

This finding captures in a nutshell one of the main benefits of Buddhist meditation practice: the opportunity to use difficult conditions--and the disturbing emotions that usually accompany them--to unlock the power and potential of the human mind.

Many people never discover this transformative capacity or the breadth of inner freedom it allows. Simply coping with the internal and external challenges that present themselves on a daily basis leaves little time for reflection--for taking what might be called a "mental step back" to evaluate our habitual responses to day-to-day events and consider that perhaps there may be other options. Over time, a deadening sense of inevitability sets in: This is the way I am, this is the way life works, there's nothing I can do to change it. In most cases, people aren't even aware of this way of seeing themselves and the world around them. This basic attitude of hopelessness sits like a layer of sludge on the bottom of a river, present but unseen.

Basic hopelessness affects people regardless of their circumstances. In Nepal, where I grew up, material comforts were few and far between. We had no electricity, no telephones, no heating or air-conditioning systems, and no running water. Every day someone would have to walk down a long hill to the river and collect water in a jug, carry it back uphill, empty the jug into a big cistern, and then trudge back down to fill the jug again. It took ten trips back and forth to collect enough water for just one day. Many people didn't have enough food to feed their families. Even though Asians are traditionally shy when it comes to discussing their feelings, anxiety and despair were evident in their faces and in the way they carried themselves as they went about the daily struggle to survive.

When I made my first teaching trip to the West in 1998, I naively assumed that with all the modern conveniences available to them, people would be much more confident and content with their lives. Instead, I discovered that there was just as much suffering as I saw at home, although it took different forms and sprang from different sources. This struck me as a very curious phenomenon. "Why is this?" I'd ask my hosts. "Everything's so great here. You have nice homes, nice cars, and good jobs. Why is there so much unhappiness?" I can't say for sure whether Westerners are simply more open to talking about their problems or whether the people I asked were just being polite. But before long, I received more answers than I'd bargained for.

In short order, I learned that traffic jams, crowded streets, work deadlines, paying bills, and long lines at the bank, the post office, airports, and grocery stores were common causes of tension, irritation, anxiety, and anger. Relationship problems at home or at work were frequent causes of emotional upset. Many people's lives were so crammed with activity that finally coming to the end of a long day was enough to make them wish that the world and everybody in it would just go away for a while. And once people did manage to get through the day, put their feet up, and start to relax, the telephone would ring or the neighbor's dog would start barking--and instantly whatever sense of contentment they may have settled into would be shattered.

Listening to these explanations, I gradually came to realize that the time and effort people spend on accumulating and maintaining material or "outer wealth" affords very little opportunity to cultivate "inner wealth"--qualities such as compassion, patience, generosity, and equanimity. This imbalance leaves people particularly vulnerable when facing serious issues like divorce, severe illness, and chronic physical or emotional pain. As I've traveled around the world over the past decade teaching courses in meditation and Buddhist philosophy, I've met people who are completely at a loss when it comes to dealing with the challenges life presents them. Some, having lost their jobs, are consumed by a fear of poverty, of losing their homes, and of never being able to get back on their feet. Others struggle with addiction or the burden of dealing with children or other family members suffering from _severe emotional or behavioral problems. An astonishing number of people are crippled by depression, self-hatred, and agonizing low self-esteem.

Many of these people have already tried a number of approaches to break through debilitating emotional patterns or find ways to cope with stressful situations. They're attracted to Buddhism because they've read or heard somewhere that it offers a novel method of overcoming pain and attaining a measure of peace and well-being. It often comes as a shock that the teachings and practices laid out by the Buddha twenty-five hundred years ago do not in any way involve conquering problems or getting rid of the sense of loneliness, discomfort, or fear that haunts our daily lives. On the contrary, the Buddha taught that we can find our freedom only through embracing the conditions that trouble us.

I can understand the dismay some people feel as this message sinks in. My own childhood and early adolescence were colored so deeply by anxiety and fear that all I could think of was escape.

RUNNING IN PLACE

To the extent that one allows desire (or any other emotion) to express itself, one correspondingly finds out how much there is that wants to be expressed.

--Kalu Rinpoche, Gently Whispered, compiled, edited, and annotated by Elizabeth Selandia

As an extremely sensitive child, I was at the mercy of my emotions. My moods swung dramatically in response to external situations. If someone smiled at me or said something nice, I'd be happy for days. The slightest problem--if I failed a test, for example, or if someone scolded me--I wanted to disappear. I was especially nervous around strangers: I'd start to shake, my throat would close up, and I'd get dizzy.

The unpleasant situations far outnumbered the pleasant ones, and for most of my early life the only relief I could find was by running away into the hills surrounding my home and sitting by myself in one of the many caves there. These caves were very special places where generations of Buddhist practitioners had sat for long periods in meditative retreats. I could almost feel their presence and the sense of mental calmness they'd achieved. I'd imitate the posture I'd seen my father--Tulku Urgyen Rinpoche, a great meditation master--and his students adopt, and I'd pretend to meditate. I'd had no formal training as yet, but just sitting there, feeling the presence of these older masters, a sense of stillness would creep over me. Time seemed to stop. Then, of course, I'd come down from the caves and my grandmother would scold me for disappearing. Whatever calmness I'd begun to feel would instantly evaporate.

Things got a little better around the age of nine, when I started training formally with my father. But--and this is a little embarrassing to admit for someone who travels around the world teaching meditation--while I liked the idea of meditation and the promise it represented, I really didn't like the practice. I'd itch; my back would hurt; my legs would go numb. So many thoughts buzzed through my mind that I found it impossible to focus. I'd be distracted by wondering, "What would happen if there was an earthquake, or a storm?" I was especially afraid of the storms that swept through the region, which were quite dramatic, full of lightning and booming thunder. I was, truth be told, the very model of the sincere practitioner who never practices.

A good meditation teacher--and my father was one of the best--will usually ask his or her students about their meditation experiences. This is one of the ways a master gauges a student's development. It's very hard to hide the truth from a teacher skilled in reading the signs of progress, and even harder when that teacher is your own father. So, even though I felt I was disappointing him, I really didn't have any choice except to tell him the truth.

As it turned out, being honest was the best choice I could have made. Experienced teachers have, themselves, usually passed through most of the difficult stages of practice. It's very rare for someone to achieve perfect stability the first time he or she sits down to meditate. Even such rare individuals have learned from their own teachers and from the texts written by past masters about the various types of problems people face. And, of course, someone who has taught hundreds of students over many years will have undoubtedly heard just about every possible complaint, frustration, and misunderstanding that will arise over the course of training. The depth and breadth of knowledge such a teacher accumulates makes it easy to determine the precise remedy for a particular problem and to have an intuitive understanding of precisely how to present it.

I'm forever grateful for the kind way my father responded to my confession that I was so hopelessly caught up by distractions that I couldn't follow even the simplest meditation instructions, like focusing on a visual object. First, he told me not to worry; distractions were normal, he said, especially in the beginning. When people first start to practice meditation all sorts of things pop up in their minds, like twigs carried along by a rushing river. The "twigs" might be physical sensations, emotions, memories, plans, even thoughts like "I can't meditate." So it was only natural to be carried away by these things, to get caught up, for instance, in wondering, Why can't I meditate? What's wrong with me? Everyone else in the room seems to be able to follow the instructions, why is it so hard for me? Then he explained that whatever was passing through my mind at any given moment was exactly the right thing to focus on, because that was where my attention was anyway.

It's the act of paying attention, my father explained, that gradually slows the rushing river in a way that would allow me to experience a little bit of space between what I was looking at and the simple awareness of looking. With practice, that space would grow longer and longer. Gradually, I'd stop identifying with the thoughts, emotions, and sensations I was experiencing and begin to identify with the pure awareness of experience.

I can't say that my life was immediately transformed by these instructions, but I found great comfort in them. I didn't have to run away from distractions or let distractions run away with me. I could, so to speak, "run in place," using whatever came up--thoughts, feelings, sensations--as opportunities to become acquainted with my mind.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

—“Paper Cuts” blog, NewYorkTimes.com

“[Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche] has written an unusually lucid and graceful addition to the modern canon….The exceptionally clear descriptions combined with Mingyur’s compassion and gentle wisdom make this book a valuable guide to Buddhist practice.”

—Publishers Weekly

“Talking to Mingyur Rinpoche is like sipping chamomile tea. He has spent a lifetime cultivating calm. But, as a child, he says, he was plagued by nearly debilitating anxiety attacks. He moved beyond them, not by trying to be the master of this problem or by becoming its slave. He made friends with the problem. This is a third approach to adversity and one that Americans rarely consider.”

–Arizona Republic

Praise for The Joy of Living

"Compelling, readable, and informed."

–Buddhadharma

“Rinpoche ’s investigations into the science of happiness are woven into an accessible introduction to Buddhism.”

–Tricycle

“I rejoice in this book, the first of its kind, a truly compelling and infinitely practical fusion of Tibetan Buddhism and scientific ideas.”

–Sogyal Rinpoche, author of The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

“There is real wisdom here. Fresh and clear. Mingyur Rinpoche has offered us what may well be an essential link between the Buddha and contemporary neuroscience and physics. He effortlessly makes connections between seemingly disparate and complex disciplines and makes the journey sparkle.”

–Richard Gere

“An extraordinarily clear book.”

–Jon Kabat-Zinn, author of Coming to Our Senses and vice-chair of the Mind and Life Institute

“[P]ersonal, readable, and wonderfully warm.”

–Sharon Salzberg, author of Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness

“Mingyur Rinpoche ’s unique contribution to this emerging field is an early flowering of the interface of neuroscience and Buddhism. . . . I heartily recommend this to anyone interested in the healing arts, consciousness studies, and genuine contemplative practice

today.”

–Lama Surya Das, author of Awakening the Buddha Within: Tibetan Wisdom for the Western World and founder of the Dzogchen Center in America

“Mingyur Rinpoche is a charismatic teacher with a heart and smile of gold. . . . This is one of those rare books where you meet the author and learn from his radiance.”

–Lou Reed

“This book is a must-read for anyone interested in the causes and consequences of happiness.”

–Richard J. Davidson, director of the Waisman Laboratory for Brain Imaging and Behavior at the University of Wisconsin—Madison

“We are lucky and blessed to have the possibility to hear the candid, down-to-earth, and beyond the consciousness of imagination generosity that Mingyur Rinpoche exudes in his teachings.”

–Julian Schnabel

From the Hardcover edition.

Descriere

In this remarkable sequel to his book, The Joy of Living, Buddhist scholar and teacher Yongey Mingyur Rinpoche explores the role of positive thinking and how to overcome anxiety in everyday life.

Joyful Wisdom is divided into three parts, the way traditional Buddhist texts are organized:

* Part One offers an overview of the basic unease we feel, how it evolved, its true source.

* Part Two describes the methods of meditation that transforms our experiences into deeper insights.

*Part Three explores the application of these methods to emotional, physical, and personal problems.

Each chapter is underlined by examples drawn from Yongey Mingyur's personal experience, the stories of friends and teachers, and in particular the conversations with people he's met during the 12 years he has spent teaching around the world.