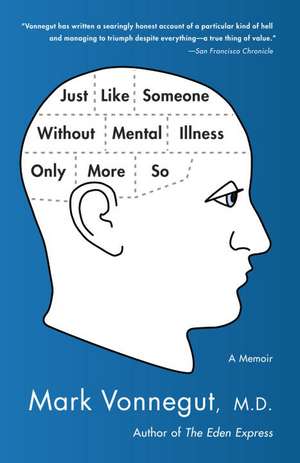

Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So: A Memoir

Autor Mark Vonneguten Limba Engleză Paperback – 11 oct 2011

Here is Mark’s life childhood as the son of a struggling writer, as well as the world after Mark was released from a mental hospital. At the late age of twenty-eight and after nineteen rejections, he is finally accepted to Harvard Medical School, where he gains purpose, a life, and some control over his condition. There are the manic episodes, during which he felt burdened with saving the world, juxtaposed against the real-world responsibilities of running a pediatric practice.

Ultimately a tribute to the small, daily, and positive parts of a life interrupted by bipolar disorder, Just Like Someone Without Mental Illness Only More So is a wise, unsentimental, and inspiring book that will resonate with generations of readers.

Preț: 109.24 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 164

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.90€ • 21.83$ • 17.26£

20.90€ • 21.83$ • 17.26£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 25 martie-08 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780385343800

ISBN-10: 0385343809

Pagini: 224

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Bantam

ISBN-10: 0385343809

Pagini: 224

Ilustrații: illustrations

Dimensiuni: 133 x 203 x 13 mm

Greutate: 0.18 kg

Editura: Bantam

Notă biografică

Mark Vonnegut is the only son of the late Kurt Vonnegut and Jane Cox Vonnegut and the author of The Eden Express: A Memoir of Insanity, an ALA Notable Book. A full-time practicing pediatrician, he lives in Massachusetts with his wife and son.

Extras

Chapter One

A Brief Family History

It's good to have a sixth gear, but watch out for

the seventh one. If you think too well outside the box,

you might find yourself in a little room without much in it.

The arts are not extracurricular.

One hundred thirty-nine years ago, my great-grandfather Bernard Vonnegut, fifteen years old, described as less physically robust than his two older brothers, probably asthmatic, started crying while doing inventory at the family hardware store. When his parents asked what was wrong, he said he didn't know but he thought he wanted to be an artist.

"I don't want to sell nails," he sobbed.

Maybe his parents should have beaten him for being ungrateful, but they wanted their son to be happy and the business was successful enough that they could hire someone else to do inventory. He became an apprentice stonecutter and then went to Europe to study art and architecture. He designed many buildings in Indianapolis that still stand today. He drew beautifully, made sculptures and furniture. He was also happily

married and had three children, one of whom was Kurt senior, my grandfather, who was known as "Doc" and who also became an architect. Doc could also draw and paint and make furniture. He made wonderful chessboards, one of which he gave to me when I was nine.

When he was sixty, Doc was pulled over for not stopping at a stop sign. The cop was astonished to notice that his driver's license had expired twenty years earlier.

"So shoot me," said Doc.

At the end of his life, which had included financial ruin in the Great Depression, his wife's barbiturate addiction and death by overdose, and then his own lung cancer, Doc said, "It was enough to have been a unicorn." What he meant was that he got to do art. It was magic to him that his hands and mind got to make wonderful things, that he didn't have to be just another goat or horse.

When I worked on the Harvard Medical School admissions committee, artistic achievements were referred to as "extras." The arts are not extra.

If my great-grandfather Bernard Vonnegut hadn't started crying while doing inventory at Vonnegut Hardware and hadn't told his parents that he wanted to be an artist instead of selling nails and if his parents hadn't figured out how to help him make that happen, there are many buildings in and around Indianapolis that wouldn't have gotten built. Kurt senior wouldn't have created paintings or furniture or carvings or stained glass. And Kurt junior, if he existed at all, would have been just another guy with PTSD-no stories, no novels, no paintings. And I, if I existed at all, would have been just another broken young man without a clue how to get up off the floor.

Art is lunging forward without certainty about where you are going or how to get there, being open to and dependent on what luck, the paint, the typo, the dissonance, give you. Without art you're stuck with yourself as you are and life as you think life is.

Craziness also runs in the family. I can trace manic depression back several generations. We have episodes of hearing voices, delusions, hyper-religiosity, and periods of not being able to eat or sleep. These episodes are remarkably similar across generations and between individuals. It's like an apocalyptic disintegration sequence that might be useful if the world really is ending, but if the world is not ending, you just end up in a nuthouse. If we're lucky enough to get better, we have to deal with people who seem unaware of our heroism and who treat us as if we are just mentally ill.

My great-grandfather on my mother's side drank to keep the voices away and ended up the town drunk in the middle of Indiana. My maternal grandmother wrote textbooks on teaching Greek and Latin and had several bouts of illness that resulted in long hospitalizations. When my mother, Jane, was in college the family resources were exhausted after my grandmother spent over two years in a private hospital. With great shame and embarrassment her husband transferred her to a state hospital, where she became well enough to go home a few weeks later. She remained mostly well and never had to be hospitalized again, but she had spent roughly seven years of my mother's childhood institutionalized.

There was no acknowledgment of or conversation about my grandmother's illness either between my mother and her father or my mother and her brother, who would also be in and out of hospitals most of his life. He emerged normal enough to marry three times in his fifties and sixties, hold a job as a librarian, and be the Indiana State senior Ping-Pong champion.

This same maternal grandmother warned my mother not to marry my father because she was convinced there was mental instability in the Vonnegut family. My father's mother, a barbiturate addict who didn't come out of her room let alone the house for weeks at a time, told my father to stay away from my mother because there was mental illness in the Cox family. My father's mother famously (some say it was an accident, but does it really make a difference?) overdosed and killed herself on Mother's Day. Barbiturates had been prescribed to my grandmother as a wonderful new nonaddictive medicine for headaches and insomnia.

If you want to pick out the people who go crazy from time to time in my family, find the ones in the photos who look ten or more years younger than they actually are. Maybe it's because we laugh and cry a lot and have a hard time figuring out what to do next. It keeps the facial muscles toned up.

It's the agitation and the need to do something about the voices that get you into trouble. If you could just lie there and watch it all go by like a movie, there would be no problem. My mother, who was radiant, young, and beautiful even as she lay dying, heard voices and saw visions, but she always managed to make friends with them and was much too charming to hospitalize even at her craziest.

If you don't have flights of ideas, why bother to think at all? I don't see how people without loose associations and flights of ideas get much done.

The reason creativity and craziness go together is that if you're just plain crazy without being able to sing or dance or write good poems, no one is going to want to have babies with you. Your genes will fall by the wayside. Who but a brazen crazy person would go one- on-one with blank paper or canvas armed with nothing but ideas?

The psychotic state is a destructive process. A fire can't burn that brightly without melting circuits. Making allowances for individual tolerances and intensity and duration of the breaks, complete functional recovery becomes increasingly unlikely much beyond about eight or nine breaks. Fixed delusions, fears, loss of flexibility, loss of concrete thinking, and low stress tolerance make relationships, jobs, and family next to impossible and then impossible. The biggest risk factor in determining whether or not you have a nineteenth psychotic episode is having had the eighteenth.

Life for the unwell is discontinuous and unpredictable. Things just come out of nowhere. People try but mostly do a lousy job of taking care of you.

Chapter Two

Raised by Wolves

The biggest gift of being unambiguously mentally ill

is the time I've saved myself trying to be normal.

I grew up on Cape Cod. The vine forest a couple hundred yards from our house was two and a half acres of trees being wrestled down and killed by honeysuckle vines and wild grapes. There were flesh-tearing bull briars throughout the lower level. There was one path that got you into the vine forest and out the other side, where the abandoned apple orchard and old foundation were. I could hit that wall of green at a full run with a knife and fishing rod and disappear. I doubt anyone could have followed me even if they saw where I went in. I built wolf dens in the vine forest next to the pond and imagined I could live there if I had to. My mother was storing canned goods and water in the crawlspace under the house in case of nuclear war.

I was mostly left alone to figure things out. If I'd been raised by wolves, I would have known a little less, but not much less, about how normal people did things. My notions about how to brush my teeth, what could be left out of the refrigerator for how long, and where knives and forks and spoons went were odd. Having been raised by wolves would have given me an excuse. But I just had beautiful, slightly broken, self-absorbed parents like a lot of other people. One of the things I couldn't figure out was why I had such lousy handwriting and why I couldn't spell.

I fought at school almost every day during grades three, four, and five. I won most fights and was never mad or emotional about it. It was just the way it was.

What I liked best about the stories of children raised by wolves was that everyone snuggled in together in a nice warm den. And then there was the part when the people find you and teach you how to talk and wear clothes.

I had a rich, full, and seemingly complete world before I knew much. My father tried to explain about sex to me when I said "Fuck you" after a chess game. I said it in a perfectly cordial way; it was something I had heard and was trying to use in a sentence. Kurt told me something about going to the bathroom in the same toilet that sounded highly improbable.

When I knocked a few dozen bricks out of a partitioning half-wall under the barn and started making a bomb shelter, it was meant as a present to my father. It was something I thought he would have gotten around to eventually. I was surprised that he wasn't more pleased. He thought that knocking those bricks out made it more likely that the already wobbly barn would fall over.

At this time in my life, my father was a proudly antisocial man who spent most of his time at a typewriter, reflecting negatively on his neighbors and society, throwing in things like "Goddamn it, you've got to be kind." The emphasis was on the Goddamn it. He was proud of the fact that I had no friends.

Later, I could never get used to him dressing nicely and talking nicely and smoothly navigating social situations with people he had taught me to hate. I thought, and still think, he taught me to play chess partly to make sure I didn't fit in with the locals my age.

When I was ten I told my mother I wanted to kill myself. I was failing at school and sports and fighting every day and had been studying poisons. My mother told me that bright young idealistic people like myself were going to save the world. It was a successful play for time. Before I killed myself I should at least join forces with all the other suicidal ten-year-olds and give saving the world a try. When the sixties came around and there didn't seem to be any adult plans worth much, I thought my mother's solution was coming to pass. Making the world a place worth saving was up to the outcasts. Who would have guessed in the fifties that there would be such a thing as hippies?

When I had three psychotic breaks in three months and I didn't think getting better was possible, my childhood looked particularly dark and dismal. Now, not so bad.

I liked to take my fishing rod and my bike and go through the woods looking for hidden ponds, which I imagined had never been fished before except maybe by Indians a long time ago. Dense rings of brambles and underbrush protected the ponds and fish.

One bright sunny August afternoon I was cruising the dirt back roads that ran along the spine of the Cape and went straight instead of taking the usual left to Hathaway's Pond. Twenty yards ahead I found myself at a dead end, facing a chain-link fence. At the top there was a two-foot-wide chain-link lip slanted back away from me at a forty- five-degree angle. I threw my bike over the fence. I expected Hathaway's or some other pond to be more or less ahead of me.

Hathaway's was one of the town's bigger ponds and one of the few that had anything like a sandy beach. Toward the end of my childhood, the powers that be decided to poison the pond so that they could get rid of the pickerel and bass and horned pout and turtles and stock it with trout. I had bad dreams about grown-ups killing all the pickerel in Hathaway's Pond-it was death on an unimaginable scale. It would have broken my heart to see the fish I had been trying to catch strewn around dead.

Why were trout better than pickerel and horned pout?

I stumbled up onto a divided four-lane highway. I couldn't have been any more surprised if I had found China. It had to be over a hundred degrees up there, at least twenty degrees hotter than it had been on the sandy, pine-shaded dirt road. A maintenance crew was spraying thick, hot oil on the shoulder, probably to keep the weeds down. Turning left would have brought me to the Barnstable Road overpass and familiarity within a hundred yards or less, but I chose to go right. Maybe it was to go with the traffic instead of having to face it.

The oil was awful. I checked the chain-link fence every so often, hoping for a break. I tried to ride my bike, but it was all gummed up with oil. I had to push it. Maybe I should have left it there and come back for it. I was going through the spit-warm water in my canteen quickly. Vacationers streamed off the Cape past the quaint ten-year-old boy with a fishing rod bent over his bike pushing it through the oil and dirt in the hundred-plus-degree heat. No one in his right mind would have stopped to let this dirty little boy and his bike into their car. I existed without an explanation. I was out of water.

I pushed my gummed-up bike along the burning shoulder of a divided limited-access highway for 2.7 miles before I saw Howard Johnson's and the Route 132 exit. The Howard Johnson's was the only place we went out to eat as a family, and that had only happened once. It didn't go well. I ordered a 3-D burger, a two-patty triple-decker precursor to the Big Mac. I can't remember exactly what went wrong, but I might have been stuttering or laughing or chewing gum when the waitress asked me what I wanted, or maybe it was something one of my sisters did. We left under a cloud. My father went stiff and red whenever there was a hint of public humiliation.

From the Hardcover edition.

A Brief Family History

It's good to have a sixth gear, but watch out for

the seventh one. If you think too well outside the box,

you might find yourself in a little room without much in it.

The arts are not extracurricular.

One hundred thirty-nine years ago, my great-grandfather Bernard Vonnegut, fifteen years old, described as less physically robust than his two older brothers, probably asthmatic, started crying while doing inventory at the family hardware store. When his parents asked what was wrong, he said he didn't know but he thought he wanted to be an artist.

"I don't want to sell nails," he sobbed.

Maybe his parents should have beaten him for being ungrateful, but they wanted their son to be happy and the business was successful enough that they could hire someone else to do inventory. He became an apprentice stonecutter and then went to Europe to study art and architecture. He designed many buildings in Indianapolis that still stand today. He drew beautifully, made sculptures and furniture. He was also happily

married and had three children, one of whom was Kurt senior, my grandfather, who was known as "Doc" and who also became an architect. Doc could also draw and paint and make furniture. He made wonderful chessboards, one of which he gave to me when I was nine.

When he was sixty, Doc was pulled over for not stopping at a stop sign. The cop was astonished to notice that his driver's license had expired twenty years earlier.

"So shoot me," said Doc.

At the end of his life, which had included financial ruin in the Great Depression, his wife's barbiturate addiction and death by overdose, and then his own lung cancer, Doc said, "It was enough to have been a unicorn." What he meant was that he got to do art. It was magic to him that his hands and mind got to make wonderful things, that he didn't have to be just another goat or horse.

When I worked on the Harvard Medical School admissions committee, artistic achievements were referred to as "extras." The arts are not extra.

If my great-grandfather Bernard Vonnegut hadn't started crying while doing inventory at Vonnegut Hardware and hadn't told his parents that he wanted to be an artist instead of selling nails and if his parents hadn't figured out how to help him make that happen, there are many buildings in and around Indianapolis that wouldn't have gotten built. Kurt senior wouldn't have created paintings or furniture or carvings or stained glass. And Kurt junior, if he existed at all, would have been just another guy with PTSD-no stories, no novels, no paintings. And I, if I existed at all, would have been just another broken young man without a clue how to get up off the floor.

Art is lunging forward without certainty about where you are going or how to get there, being open to and dependent on what luck, the paint, the typo, the dissonance, give you. Without art you're stuck with yourself as you are and life as you think life is.

Craziness also runs in the family. I can trace manic depression back several generations. We have episodes of hearing voices, delusions, hyper-religiosity, and periods of not being able to eat or sleep. These episodes are remarkably similar across generations and between individuals. It's like an apocalyptic disintegration sequence that might be useful if the world really is ending, but if the world is not ending, you just end up in a nuthouse. If we're lucky enough to get better, we have to deal with people who seem unaware of our heroism and who treat us as if we are just mentally ill.

My great-grandfather on my mother's side drank to keep the voices away and ended up the town drunk in the middle of Indiana. My maternal grandmother wrote textbooks on teaching Greek and Latin and had several bouts of illness that resulted in long hospitalizations. When my mother, Jane, was in college the family resources were exhausted after my grandmother spent over two years in a private hospital. With great shame and embarrassment her husband transferred her to a state hospital, where she became well enough to go home a few weeks later. She remained mostly well and never had to be hospitalized again, but she had spent roughly seven years of my mother's childhood institutionalized.

There was no acknowledgment of or conversation about my grandmother's illness either between my mother and her father or my mother and her brother, who would also be in and out of hospitals most of his life. He emerged normal enough to marry three times in his fifties and sixties, hold a job as a librarian, and be the Indiana State senior Ping-Pong champion.

This same maternal grandmother warned my mother not to marry my father because she was convinced there was mental instability in the Vonnegut family. My father's mother, a barbiturate addict who didn't come out of her room let alone the house for weeks at a time, told my father to stay away from my mother because there was mental illness in the Cox family. My father's mother famously (some say it was an accident, but does it really make a difference?) overdosed and killed herself on Mother's Day. Barbiturates had been prescribed to my grandmother as a wonderful new nonaddictive medicine for headaches and insomnia.

If you want to pick out the people who go crazy from time to time in my family, find the ones in the photos who look ten or more years younger than they actually are. Maybe it's because we laugh and cry a lot and have a hard time figuring out what to do next. It keeps the facial muscles toned up.

It's the agitation and the need to do something about the voices that get you into trouble. If you could just lie there and watch it all go by like a movie, there would be no problem. My mother, who was radiant, young, and beautiful even as she lay dying, heard voices and saw visions, but she always managed to make friends with them and was much too charming to hospitalize even at her craziest.

If you don't have flights of ideas, why bother to think at all? I don't see how people without loose associations and flights of ideas get much done.

The reason creativity and craziness go together is that if you're just plain crazy without being able to sing or dance or write good poems, no one is going to want to have babies with you. Your genes will fall by the wayside. Who but a brazen crazy person would go one- on-one with blank paper or canvas armed with nothing but ideas?

The psychotic state is a destructive process. A fire can't burn that brightly without melting circuits. Making allowances for individual tolerances and intensity and duration of the breaks, complete functional recovery becomes increasingly unlikely much beyond about eight or nine breaks. Fixed delusions, fears, loss of flexibility, loss of concrete thinking, and low stress tolerance make relationships, jobs, and family next to impossible and then impossible. The biggest risk factor in determining whether or not you have a nineteenth psychotic episode is having had the eighteenth.

Life for the unwell is discontinuous and unpredictable. Things just come out of nowhere. People try but mostly do a lousy job of taking care of you.

Chapter Two

Raised by Wolves

The biggest gift of being unambiguously mentally ill

is the time I've saved myself trying to be normal.

I grew up on Cape Cod. The vine forest a couple hundred yards from our house was two and a half acres of trees being wrestled down and killed by honeysuckle vines and wild grapes. There were flesh-tearing bull briars throughout the lower level. There was one path that got you into the vine forest and out the other side, where the abandoned apple orchard and old foundation were. I could hit that wall of green at a full run with a knife and fishing rod and disappear. I doubt anyone could have followed me even if they saw where I went in. I built wolf dens in the vine forest next to the pond and imagined I could live there if I had to. My mother was storing canned goods and water in the crawlspace under the house in case of nuclear war.

I was mostly left alone to figure things out. If I'd been raised by wolves, I would have known a little less, but not much less, about how normal people did things. My notions about how to brush my teeth, what could be left out of the refrigerator for how long, and where knives and forks and spoons went were odd. Having been raised by wolves would have given me an excuse. But I just had beautiful, slightly broken, self-absorbed parents like a lot of other people. One of the things I couldn't figure out was why I had such lousy handwriting and why I couldn't spell.

I fought at school almost every day during grades three, four, and five. I won most fights and was never mad or emotional about it. It was just the way it was.

What I liked best about the stories of children raised by wolves was that everyone snuggled in together in a nice warm den. And then there was the part when the people find you and teach you how to talk and wear clothes.

I had a rich, full, and seemingly complete world before I knew much. My father tried to explain about sex to me when I said "Fuck you" after a chess game. I said it in a perfectly cordial way; it was something I had heard and was trying to use in a sentence. Kurt told me something about going to the bathroom in the same toilet that sounded highly improbable.

When I knocked a few dozen bricks out of a partitioning half-wall under the barn and started making a bomb shelter, it was meant as a present to my father. It was something I thought he would have gotten around to eventually. I was surprised that he wasn't more pleased. He thought that knocking those bricks out made it more likely that the already wobbly barn would fall over.

At this time in my life, my father was a proudly antisocial man who spent most of his time at a typewriter, reflecting negatively on his neighbors and society, throwing in things like "Goddamn it, you've got to be kind." The emphasis was on the Goddamn it. He was proud of the fact that I had no friends.

Later, I could never get used to him dressing nicely and talking nicely and smoothly navigating social situations with people he had taught me to hate. I thought, and still think, he taught me to play chess partly to make sure I didn't fit in with the locals my age.

When I was ten I told my mother I wanted to kill myself. I was failing at school and sports and fighting every day and had been studying poisons. My mother told me that bright young idealistic people like myself were going to save the world. It was a successful play for time. Before I killed myself I should at least join forces with all the other suicidal ten-year-olds and give saving the world a try. When the sixties came around and there didn't seem to be any adult plans worth much, I thought my mother's solution was coming to pass. Making the world a place worth saving was up to the outcasts. Who would have guessed in the fifties that there would be such a thing as hippies?

When I had three psychotic breaks in three months and I didn't think getting better was possible, my childhood looked particularly dark and dismal. Now, not so bad.

I liked to take my fishing rod and my bike and go through the woods looking for hidden ponds, which I imagined had never been fished before except maybe by Indians a long time ago. Dense rings of brambles and underbrush protected the ponds and fish.

One bright sunny August afternoon I was cruising the dirt back roads that ran along the spine of the Cape and went straight instead of taking the usual left to Hathaway's Pond. Twenty yards ahead I found myself at a dead end, facing a chain-link fence. At the top there was a two-foot-wide chain-link lip slanted back away from me at a forty- five-degree angle. I threw my bike over the fence. I expected Hathaway's or some other pond to be more or less ahead of me.

Hathaway's was one of the town's bigger ponds and one of the few that had anything like a sandy beach. Toward the end of my childhood, the powers that be decided to poison the pond so that they could get rid of the pickerel and bass and horned pout and turtles and stock it with trout. I had bad dreams about grown-ups killing all the pickerel in Hathaway's Pond-it was death on an unimaginable scale. It would have broken my heart to see the fish I had been trying to catch strewn around dead.

Why were trout better than pickerel and horned pout?

I stumbled up onto a divided four-lane highway. I couldn't have been any more surprised if I had found China. It had to be over a hundred degrees up there, at least twenty degrees hotter than it had been on the sandy, pine-shaded dirt road. A maintenance crew was spraying thick, hot oil on the shoulder, probably to keep the weeds down. Turning left would have brought me to the Barnstable Road overpass and familiarity within a hundred yards or less, but I chose to go right. Maybe it was to go with the traffic instead of having to face it.

The oil was awful. I checked the chain-link fence every so often, hoping for a break. I tried to ride my bike, but it was all gummed up with oil. I had to push it. Maybe I should have left it there and come back for it. I was going through the spit-warm water in my canteen quickly. Vacationers streamed off the Cape past the quaint ten-year-old boy with a fishing rod bent over his bike pushing it through the oil and dirt in the hundred-plus-degree heat. No one in his right mind would have stopped to let this dirty little boy and his bike into their car. I existed without an explanation. I was out of water.

I pushed my gummed-up bike along the burning shoulder of a divided limited-access highway for 2.7 miles before I saw Howard Johnson's and the Route 132 exit. The Howard Johnson's was the only place we went out to eat as a family, and that had only happened once. It didn't go well. I ordered a 3-D burger, a two-patty triple-decker precursor to the Big Mac. I can't remember exactly what went wrong, but I might have been stuttering or laughing or chewing gum when the waitress asked me what I wanted, or maybe it was something one of my sisters did. We left under a cloud. My father went stiff and red whenever there was a hint of public humiliation.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

NAMED ONE OF THE BEST BOOKS OF THE YEAR BY

San Francisco Chronicle • Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Vonnegut has written a searingly honest account of a particular kind of hell and managing to triumph despite everything—a true thing of value.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“[Mark] Vonnegut shares with his late father a knack for throwing down sentences—many sentences—of such naked wit and intelligence they make a reader stop for an extra beat.”—San Jose Mercury News

“[A] remarkable new memoir . . . many fascinating accounts of what it was like growing up with a still-struggling writer father.”—The Boston Globe

“Mark Vonnegut tells a strange and funny story in a strong, tensile style—at their frequent best, his sentences are like shards of colored glass: beautiful, but liable to cause damage.”—Palm Beach Post

“Mordantly witty, slightly subversive.”—Publishers Weekly

San Francisco Chronicle • Milwaukee Journal Sentinel

“Vonnegut has written a searingly honest account of a particular kind of hell and managing to triumph despite everything—a true thing of value.”—San Francisco Chronicle

“[Mark] Vonnegut shares with his late father a knack for throwing down sentences—many sentences—of such naked wit and intelligence they make a reader stop for an extra beat.”—San Jose Mercury News

“[A] remarkable new memoir . . . many fascinating accounts of what it was like growing up with a still-struggling writer father.”—The Boston Globe

“Mark Vonnegut tells a strange and funny story in a strong, tensile style—at their frequent best, his sentences are like shards of colored glass: beautiful, but liable to cause damage.”—Palm Beach Post

“Mordantly witty, slightly subversive.”—Publishers Weekly