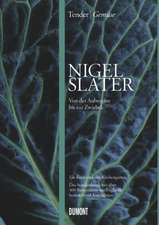

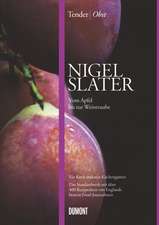

Tender

Autor Nigel Slateren Limba Engleză Hardback – 16 sep 2010

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Hardback (2) | 216.32 lei 3-5 săpt. | +76.16 lei 6-12 zile |

| HarperCollins Publishers – 16 sep 2010 | 216.32 lei 3-5 săpt. | +76.16 lei 6-12 zile |

| Ten Speed Press – 31 mar 2011 | 292.98 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 216.32 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 324

Preț estimativ în valută:

41.39€ • 44.26$ • 34.51£

41.39€ • 44.26$ • 34.51£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 28 martie-11 aprilie

Livrare express 13-19 martie pentru 86.15 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780007325214

ISBN-10: 0007325215

Pagini: 592

Ilustrații: (250 colour photographs), Index

Dimensiuni: 183 x 248 x 56 mm

Greutate: 1.73 kg

Editura: HarperCollins Publishers

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0007325215

Pagini: 592

Ilustrații: (250 colour photographs), Index

Dimensiuni: 183 x 248 x 56 mm

Greutate: 1.73 kg

Editura: HarperCollins Publishers

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Descriere

With over 300 recipe ideas and many wonderful stories from the fruit garden, Tender: Volume II – A cook’s guide to the fruit garden is the definitive guide to cooking with fruit from Britain’s finest food writer.

‘When I dug up my lawn to grow my own vegetables and herbs I planted fruit too. A handful of small trees - plum, apple and pear - some raspberry, blackberry and currant bushes and even strawberries in pots suddenly joined my patch of potatoes, beans and peas. These fruits became the backbone of my home baking, the stars in my cakes and pastries and even inspired the odd pot of jam. More than this, I started to use them in new ways too, from a weekday supper of pork chops with cider and apples to a Chinese Sunday roast with spiced plum sauce. The hot family puddings and fruit ices we had always loved so much suddenly took on a delicious new significance.’ (Nigel Slater)

Notă biografică

Nigel Slater is the author of a collecion of bestselling books including the classics Real Fast Food, Appetite, and the critically acclaimed The Kitchen Diaries. He has written a much-loved column for The Observer for seventeen years. His memoir, Toast —The Story of a Boy’s Hunger, has won six major awards, including British Biography of the Year. Visit www.nigelslater.com.

Extras

There is a moment in late April, somewhere between the end of the plum blossom and the height of the apple, just as the Holly Blue butterflies start to appear in the garden, that the early asparagus turns up at the farmers’ market. Tied in bunches of just six or ten, these first green and mauve spears of Asparagus officinalis are sometimes presented in a burlap-lined wicker basket, as if to endorse their fragility and their expense. Their points tightly closed, a faint, gray bloom of youth still apparent on their stems, it would take a will stronger than mine not to buy.

The older I get, the more interested I become in the shoots that the Persians called asparag, and in Pershore, the heart of the old British asparagus trade, they still call “sparrow-grass.” The farms around Kent and Suffolk sell it from open sheds an egg’s throw from the field in which it has been grown, and where I have been known to bring it back by the armful when it’s cheap enough. You see the occasional row on an allotment, but the plants take up the most space of any vegetable and require vigilant picking and careful transport home. “Grass,” as it is so often known by greengrocers and farmers alike, remains expensive for a reason.

Life is full of small rituals, and never more so than in my kitchen. The first asparagus of the year is boiled within minutes of my walking through the door with it, butter is carefully melted so that it is soft and formless but not yet liquid, then I eat it with the sort of reverence I usually reserve for mulberries or a piece of exquisite sashimi. It is almost impossible not to respect those first spears of the year.

The short, six-week season starts in late April, and once it is up and running, the price drops and the bundles get fatter. I could have it every day—in a salad with cold salmon, stirred into a frugal rice pilaf, chopped and stirred into the custard filling of a tart, or grilled and served with lemon juice and grated pecorino. I might get tired of its side effects—it contains methyl mercaptan, which makes most people’s pee stink—but its flavor is the strongest sign yet that summer has started.

By mid-June all but a few stragglers have gone, and the farmers rest their ancient plants till next spring.

Asparagus in the garden

There are days when I covet my neighbors’ untended, overgrown garden. It’s a haven for the foxes whose earth stretches far under the “lawn,” on which they lie sprawled in the sun, six at a time. The land would make a much-needed overflow for my own vegetable patch.

In celebration of the luxury of more space, my first planting would be asparagus, one of the few vegetables I have yet to grow for myself. The crowns, as the root-balls are known, take up a considerable amount of room, far more than I can afford to offer them in my own tiny garden. You can raise plants from seed, if you are capable of waiting three years for them to gather strength before your first pick. Most people buy two- or even three-year-old crowns instead. They are usually delivered in late spring, wrapped in newspaper, a mass of dangling, spiderlike roots sporting a short stalk or two. You dig them in—they thrive on sandy soil and sunshine—planting them in deep, manure-lined trenches under a generous 4 inches (10cm) of soil, and then you must pamper them with seaweed and more manure and ply them generously with drink.

As a thank you, they will send up occasional spears from late April to midsummer. Picking stimulates growth, but it is unwise to pick for too long. The farmers around my childhood home in Worcestershire would never harvest for more than six weeks for fear of exhausting the plants. Leaving a few late arrivals to develop into feathery fronds—the sort a bridegroom attaches to a buttonhole carnation—will help to restore the crown. Resting fields in growing areas can be spotted in late summer by tall fronds dotted with carmine berries, waving in the breeze.

Asparagus needs to be cut, never pulled, and you should slice as near to the crown as possible. The temptation to pick every last spear should be avoided. I have seen growers lowering their bundles into buckets of water after cutting to keep the ends moist. Dried up, they will find few takers.

Asparagus in the kitchen

There are two types of asparagus of interest, three if you count the fat “jumbo” spears, whose flavor is rarely as impressive as their size: the thin “sprue,” finer than a pencil, and the thicker spears for picking up with our fingers. Sprue is my favorite size for working into a salad with samphire, melted butter, and grated lemon. Being supple, it tangles elegantly round your fork.

The thicker spears are most tender at their flowering point, less so at the thick end where the stalk has been cut from the plant. You can often eat the entire spear, and a tough end is no real hardship—it acts as something to hold while we suck butter off the tastiest bits. Some people prefer to trim their “grass,” whittling the white end to a point with a paring knife or peeler.

Get the spears to the pot as quickly as you can. They lose their moisture and sweetness by the hour. If you have to store them (I often buy three bunches at once at the Sunday farmers’ market), stand them in a bowl of water like a bunch of flowers.

We can safely ignore the more far-fetched ways to boil asparagus, which range, in case you have a fancy to try, from standing them upright in a pan with their feet supported by new potatoes to cradling them over the water in a kitchen towel like a baby in swaddling clothes. Well intentioned, but unnecessary. Just lower the bundle of stalks tenderly into a shallow pan of merrily boiling water. If they are too long, let the points rest on the edge of the pan, where they will steam while the thicker ends tenderize in the water. They are good grilled over charcoal too, where the smokiness they take on makes up for the very slight lessening in juiciness. And they can be baked in aluminum foil or parchment paper with butter, a few sprigs of tarragon or chervil, and some moisture in the form of white wine or water so that they effectively steam in the sealed parcel.

Once we have tired of boiled asparagus and melted butter, the spears make a deeply herbaceous soup or a mild, rather soporific tart and marry well with pancetta or soft-boiled eggs. A few in a salad will make it feel extravagant, even if the only other ingredients are new potatoes, oil, lemon juice, and parsley. My all-time favorite asparagus lunch is one where a small, parchment-colored soft cheese is allowed to melt lazily over freshly boiled spears. The warm cheese oozing from its bloomy crust makes an impromptu sauce.

Seasoning your asparagus

Butter Melted, for dressing lightly cooked spears.

Lemon juice An underused seasoning for buttered asparagus. Particularly good where Parmesan is involved.

Tomato A fresh tomato sauce, made by roasting small tomatoes, crushing them with a fork, then stirring in olive oil, crushed garlic, and a splash of red wine vinegar.

Parmesan Finely grated over buttered spears or used to form a crust on a gratin of asparagus and cream.

Bacon Toss a pan of bacon or pancetta snippets and its hot fat over freshly cooked spears.

Cheese Soft, grassy cheeses, especially the richer cow’s milk varieties.

Eggs As a filling for a tart, or simply soft boiled, as a natural cup of golden sauce in which to dip lightly cooked spears.

And ...

Weed your asparagus bed by hand. A hoe may damage emerging shoots.

Despite not providing a harvest for the first three years, a crown can remain prolific for twenty years or more. I have heard of them even older.

I was taught how to pick asparagus by a grower in Evesham. He showed me how to push the soil gently away from the lower part of the stalk with your fingers to reveal the end, which you then cut as close as possible to the crown, taking care not to cut into it.

This vegetable loses its sweetness by the hour. Anything that has traveled from overseas is likely to disappoint.

Avoid cooking asparagus in aluminium pans. It can taint the spears.

Roll lightly cooked spears in thinly sliced ham, lay them in a shallow dish, cover with a cheese sauce, and a heavy dusting of Parmesan and bake until bubbling.

A pilaf of asparagus, fava beans, and mint

Asparagus is something you feel the need to gorge on, rather than finding the odd bit lurking almost apologetically in a salad or main course. The exceptions are a risotto—for which you will find a recipe in Appetite—and a simple rice pilaf. The gentle flavor of asparagus doesn’t take well to spices, but a little cinnamon or cardamom used in a buttery pilaf offers a mild, though warmly seasoned base for when we have only a small number of spears at our disposal.

enough for 2

fava beans, shelled – a couple of handfuls

thin asparagus spears – 12

white basmati rice – 2/3 cup (120g)

butter – 4 tablespoons (50g)

bay leaves – 3

green cardamom pods – 6, very lightly crushed

black peppercorns – 6

a cinnamon stick

cloves – 2 or 3, but no more

cumin seeds – a small pinch

thyme – a couple of sprigs

green onions – 4 thin ones

parsley – 3 or 4 sprigs

to accompany the pilaf

chopped mint – 2 tablespoons

olive oil – 2 tablespoons

yogurt – 3/4 cup (200g)

Cook the fava beans in deep, lightly salted boiling water for four minutes, until almost tender, then drain. Trim the asparagus and cut it into short lengths. Boil or steam for three minutes, then drain.Wash the rice three times in cold water, moving the grains around with your fingers. Cover with warm water, add a teaspoon of salt, and set aside for a good hour.

Melt the butter in a saucepan, then add the bay leaves, cardamom pods, peppercorns, cinnamon stick, cloves, cumin seeds, and sprigs of thyme. Stir them in the butter for a minute or two, until the fragrance wafts up. Drain the rice and add it to the warmed spices. Cover with about 1/4 inch (1cm) of water and bring to a boil. Season with salt, cover, and decrease the heat to simmer. Finely slice the green onions. Chop the parsley.

After five minutes, remove the lid and gently fold in the asparagus, fava beans, green onions, and parsley. Replace the lid and continue cooking for five or six minutes, until the rice is tender but has some bite to it. All the water should have been absorbed. Leave, with the lid on but the heat off, for two or three minutes. Remove the lid, add a tablespoon of butter if you wish, check the seasoning, and fluff gently with a fork. Serve with the yogurt sauce below.

To accompany the pilaf

Stir 2 tablespoons of chopped mint, a little salt, and 2 tablespoons of olive oil into 3/4 cup (200g) thick, but not strained, yogurt. You could add a small clove of crushed garlic too. Spoon over the pilaf at the table.

Warm asparagus, melted cheese

I have used Taleggio, Camembert, and English Tunworth from Hampshire as an impromptu “sauce” for warm asparagus with great success. A very soft blue would work as well.

enough for 2

thick, juicy asparagus spears – 24

a little olive oil or melted butter

soft, ripe cheeses such as St. Marcellin or any of the above – 2

Bring a deep pan of lightly salted water to a boil. Trim any woody ends from the asparagus and lower the spears gently into the water as soon as it is boiling. Cook for four or five minutes, until tender enough to bend. Lift the spears out with a slotted spoon and lower them into a shallow baking dish. Brush them lightly with olive oil or melted butter.

Preheat the broiler. Slice the cheese thickly—smaller whole cheeses can simply be sliced in half horizontally—and lay them over the top of the spears. Place under a hot broiler for four or five minutes till the cheese melts. Eat immediately, while the cheese is still runny.

A tart of asparagus and tarragon

I retain a soft spot for canned asparagus. Not as something to eat with my fingers (it is considerably softer than fresh asparagus, and rather too giving), but as something with which to flavor a quiche. The canned stuff seems to permeate the custard more effectively than the fresh. This may belong to the law that makes canned apricots better in a frangipane tart than fresh ones, or simply be misplaced nostalgia. I once made a living from making asparagus quiche, it’s something very dear to my heart. Still, fresh is good too.

enough for 6

for the pastry

butter – 7 tablespoons (90g)

all-purpose flour – 11/4 cups (150g)

an egg yolk

for the filling

medium-thick asparagus spears – 12

heavy cream – 11/4 cups (284ml)

eggs – 2

tarragon – the leaves of 4 or 5 bushy sprigs

grated pecorino or Parmesan – 3 tablespoons

Cut the butter into small chunks and rub it into the flour with your fingertips until it resembles coarse breadcrumbs. Mix in the egg yolk and enough water to make a firm dough. You will find you need about a tablespoon of water or even less.

Roll the dough out to fit a 9-inch (22cm) tart pan (life will be easier when you come to cut the tart if you have a pan with a removable bottom), pressing the pastry right into the corners. Prick the pastry base with a fork, then refrigerate it for a good twenty minutes. Don’t be tempted to miss out this step; the chilling will stop the pastry shrinking in the oven. Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C). Bake blind for twelve to fifteen minutes, until the pastry is pale golden and dry to the touch.

Decrease the oven temperature to 350°F (180°C). Bring a large pan of water to a boil, drop in the asparagus, and let it simmer for seven or eight minutes or so, until it is quite tender. It will receive more cooking later but you want it to be thoroughly soft after its time in the oven, as its texture will barely change later under the custard.

Put the cream in a pitcher or bowl and beat in the eggs gently with a fork. Coarsely chop the tarragon and add that to the cream with a seasoning of salt and black pepper. Slice the asparagus into short lengths, removing any tough ends. Scatter it over the partly baked pastry shell, then pour in the cream and egg mixture and scatter the cheese over the surface. Bake for about forty minutes, until the filling is golden and set. Serve warm.

The older I get, the more interested I become in the shoots that the Persians called asparag, and in Pershore, the heart of the old British asparagus trade, they still call “sparrow-grass.” The farms around Kent and Suffolk sell it from open sheds an egg’s throw from the field in which it has been grown, and where I have been known to bring it back by the armful when it’s cheap enough. You see the occasional row on an allotment, but the plants take up the most space of any vegetable and require vigilant picking and careful transport home. “Grass,” as it is so often known by greengrocers and farmers alike, remains expensive for a reason.

Life is full of small rituals, and never more so than in my kitchen. The first asparagus of the year is boiled within minutes of my walking through the door with it, butter is carefully melted so that it is soft and formless but not yet liquid, then I eat it with the sort of reverence I usually reserve for mulberries or a piece of exquisite sashimi. It is almost impossible not to respect those first spears of the year.

The short, six-week season starts in late April, and once it is up and running, the price drops and the bundles get fatter. I could have it every day—in a salad with cold salmon, stirred into a frugal rice pilaf, chopped and stirred into the custard filling of a tart, or grilled and served with lemon juice and grated pecorino. I might get tired of its side effects—it contains methyl mercaptan, which makes most people’s pee stink—but its flavor is the strongest sign yet that summer has started.

By mid-June all but a few stragglers have gone, and the farmers rest their ancient plants till next spring.

Asparagus in the garden

There are days when I covet my neighbors’ untended, overgrown garden. It’s a haven for the foxes whose earth stretches far under the “lawn,” on which they lie sprawled in the sun, six at a time. The land would make a much-needed overflow for my own vegetable patch.

In celebration of the luxury of more space, my first planting would be asparagus, one of the few vegetables I have yet to grow for myself. The crowns, as the root-balls are known, take up a considerable amount of room, far more than I can afford to offer them in my own tiny garden. You can raise plants from seed, if you are capable of waiting three years for them to gather strength before your first pick. Most people buy two- or even three-year-old crowns instead. They are usually delivered in late spring, wrapped in newspaper, a mass of dangling, spiderlike roots sporting a short stalk or two. You dig them in—they thrive on sandy soil and sunshine—planting them in deep, manure-lined trenches under a generous 4 inches (10cm) of soil, and then you must pamper them with seaweed and more manure and ply them generously with drink.

As a thank you, they will send up occasional spears from late April to midsummer. Picking stimulates growth, but it is unwise to pick for too long. The farmers around my childhood home in Worcestershire would never harvest for more than six weeks for fear of exhausting the plants. Leaving a few late arrivals to develop into feathery fronds—the sort a bridegroom attaches to a buttonhole carnation—will help to restore the crown. Resting fields in growing areas can be spotted in late summer by tall fronds dotted with carmine berries, waving in the breeze.

Asparagus needs to be cut, never pulled, and you should slice as near to the crown as possible. The temptation to pick every last spear should be avoided. I have seen growers lowering their bundles into buckets of water after cutting to keep the ends moist. Dried up, they will find few takers.

Asparagus in the kitchen

There are two types of asparagus of interest, three if you count the fat “jumbo” spears, whose flavor is rarely as impressive as their size: the thin “sprue,” finer than a pencil, and the thicker spears for picking up with our fingers. Sprue is my favorite size for working into a salad with samphire, melted butter, and grated lemon. Being supple, it tangles elegantly round your fork.

The thicker spears are most tender at their flowering point, less so at the thick end where the stalk has been cut from the plant. You can often eat the entire spear, and a tough end is no real hardship—it acts as something to hold while we suck butter off the tastiest bits. Some people prefer to trim their “grass,” whittling the white end to a point with a paring knife or peeler.

Get the spears to the pot as quickly as you can. They lose their moisture and sweetness by the hour. If you have to store them (I often buy three bunches at once at the Sunday farmers’ market), stand them in a bowl of water like a bunch of flowers.

We can safely ignore the more far-fetched ways to boil asparagus, which range, in case you have a fancy to try, from standing them upright in a pan with their feet supported by new potatoes to cradling them over the water in a kitchen towel like a baby in swaddling clothes. Well intentioned, but unnecessary. Just lower the bundle of stalks tenderly into a shallow pan of merrily boiling water. If they are too long, let the points rest on the edge of the pan, where they will steam while the thicker ends tenderize in the water. They are good grilled over charcoal too, where the smokiness they take on makes up for the very slight lessening in juiciness. And they can be baked in aluminum foil or parchment paper with butter, a few sprigs of tarragon or chervil, and some moisture in the form of white wine or water so that they effectively steam in the sealed parcel.

Once we have tired of boiled asparagus and melted butter, the spears make a deeply herbaceous soup or a mild, rather soporific tart and marry well with pancetta or soft-boiled eggs. A few in a salad will make it feel extravagant, even if the only other ingredients are new potatoes, oil, lemon juice, and parsley. My all-time favorite asparagus lunch is one where a small, parchment-colored soft cheese is allowed to melt lazily over freshly boiled spears. The warm cheese oozing from its bloomy crust makes an impromptu sauce.

Seasoning your asparagus

Butter Melted, for dressing lightly cooked spears.

Lemon juice An underused seasoning for buttered asparagus. Particularly good where Parmesan is involved.

Tomato A fresh tomato sauce, made by roasting small tomatoes, crushing them with a fork, then stirring in olive oil, crushed garlic, and a splash of red wine vinegar.

Parmesan Finely grated over buttered spears or used to form a crust on a gratin of asparagus and cream.

Bacon Toss a pan of bacon or pancetta snippets and its hot fat over freshly cooked spears.

Cheese Soft, grassy cheeses, especially the richer cow’s milk varieties.

Eggs As a filling for a tart, or simply soft boiled, as a natural cup of golden sauce in which to dip lightly cooked spears.

And ...

Weed your asparagus bed by hand. A hoe may damage emerging shoots.

Despite not providing a harvest for the first three years, a crown can remain prolific for twenty years or more. I have heard of them even older.

I was taught how to pick asparagus by a grower in Evesham. He showed me how to push the soil gently away from the lower part of the stalk with your fingers to reveal the end, which you then cut as close as possible to the crown, taking care not to cut into it.

This vegetable loses its sweetness by the hour. Anything that has traveled from overseas is likely to disappoint.

Avoid cooking asparagus in aluminium pans. It can taint the spears.

Roll lightly cooked spears in thinly sliced ham, lay them in a shallow dish, cover with a cheese sauce, and a heavy dusting of Parmesan and bake until bubbling.

A pilaf of asparagus, fava beans, and mint

Asparagus is something you feel the need to gorge on, rather than finding the odd bit lurking almost apologetically in a salad or main course. The exceptions are a risotto—for which you will find a recipe in Appetite—and a simple rice pilaf. The gentle flavor of asparagus doesn’t take well to spices, but a little cinnamon or cardamom used in a buttery pilaf offers a mild, though warmly seasoned base for when we have only a small number of spears at our disposal.

enough for 2

fava beans, shelled – a couple of handfuls

thin asparagus spears – 12

white basmati rice – 2/3 cup (120g)

butter – 4 tablespoons (50g)

bay leaves – 3

green cardamom pods – 6, very lightly crushed

black peppercorns – 6

a cinnamon stick

cloves – 2 or 3, but no more

cumin seeds – a small pinch

thyme – a couple of sprigs

green onions – 4 thin ones

parsley – 3 or 4 sprigs

to accompany the pilaf

chopped mint – 2 tablespoons

olive oil – 2 tablespoons

yogurt – 3/4 cup (200g)

Cook the fava beans in deep, lightly salted boiling water for four minutes, until almost tender, then drain. Trim the asparagus and cut it into short lengths. Boil or steam for three minutes, then drain.Wash the rice three times in cold water, moving the grains around with your fingers. Cover with warm water, add a teaspoon of salt, and set aside for a good hour.

Melt the butter in a saucepan, then add the bay leaves, cardamom pods, peppercorns, cinnamon stick, cloves, cumin seeds, and sprigs of thyme. Stir them in the butter for a minute or two, until the fragrance wafts up. Drain the rice and add it to the warmed spices. Cover with about 1/4 inch (1cm) of water and bring to a boil. Season with salt, cover, and decrease the heat to simmer. Finely slice the green onions. Chop the parsley.

After five minutes, remove the lid and gently fold in the asparagus, fava beans, green onions, and parsley. Replace the lid and continue cooking for five or six minutes, until the rice is tender but has some bite to it. All the water should have been absorbed. Leave, with the lid on but the heat off, for two or three minutes. Remove the lid, add a tablespoon of butter if you wish, check the seasoning, and fluff gently with a fork. Serve with the yogurt sauce below.

To accompany the pilaf

Stir 2 tablespoons of chopped mint, a little salt, and 2 tablespoons of olive oil into 3/4 cup (200g) thick, but not strained, yogurt. You could add a small clove of crushed garlic too. Spoon over the pilaf at the table.

Warm asparagus, melted cheese

I have used Taleggio, Camembert, and English Tunworth from Hampshire as an impromptu “sauce” for warm asparagus with great success. A very soft blue would work as well.

enough for 2

thick, juicy asparagus spears – 24

a little olive oil or melted butter

soft, ripe cheeses such as St. Marcellin or any of the above – 2

Bring a deep pan of lightly salted water to a boil. Trim any woody ends from the asparagus and lower the spears gently into the water as soon as it is boiling. Cook for four or five minutes, until tender enough to bend. Lift the spears out with a slotted spoon and lower them into a shallow baking dish. Brush them lightly with olive oil or melted butter.

Preheat the broiler. Slice the cheese thickly—smaller whole cheeses can simply be sliced in half horizontally—and lay them over the top of the spears. Place under a hot broiler for four or five minutes till the cheese melts. Eat immediately, while the cheese is still runny.

A tart of asparagus and tarragon

I retain a soft spot for canned asparagus. Not as something to eat with my fingers (it is considerably softer than fresh asparagus, and rather too giving), but as something with which to flavor a quiche. The canned stuff seems to permeate the custard more effectively than the fresh. This may belong to the law that makes canned apricots better in a frangipane tart than fresh ones, or simply be misplaced nostalgia. I once made a living from making asparagus quiche, it’s something very dear to my heart. Still, fresh is good too.

enough for 6

for the pastry

butter – 7 tablespoons (90g)

all-purpose flour – 11/4 cups (150g)

an egg yolk

for the filling

medium-thick asparagus spears – 12

heavy cream – 11/4 cups (284ml)

eggs – 2

tarragon – the leaves of 4 or 5 bushy sprigs

grated pecorino or Parmesan – 3 tablespoons

Cut the butter into small chunks and rub it into the flour with your fingertips until it resembles coarse breadcrumbs. Mix in the egg yolk and enough water to make a firm dough. You will find you need about a tablespoon of water or even less.

Roll the dough out to fit a 9-inch (22cm) tart pan (life will be easier when you come to cut the tart if you have a pan with a removable bottom), pressing the pastry right into the corners. Prick the pastry base with a fork, then refrigerate it for a good twenty minutes. Don’t be tempted to miss out this step; the chilling will stop the pastry shrinking in the oven. Meanwhile, preheat the oven to 400°F (200°C). Bake blind for twelve to fifteen minutes, until the pastry is pale golden and dry to the touch.

Decrease the oven temperature to 350°F (180°C). Bring a large pan of water to a boil, drop in the asparagus, and let it simmer for seven or eight minutes or so, until it is quite tender. It will receive more cooking later but you want it to be thoroughly soft after its time in the oven, as its texture will barely change later under the custard.

Put the cream in a pitcher or bowl and beat in the eggs gently with a fork. Coarsely chop the tarragon and add that to the cream with a seasoning of salt and black pepper. Slice the asparagus into short lengths, removing any tough ends. Scatter it over the partly baked pastry shell, then pour in the cream and egg mixture and scatter the cheese over the surface. Bake for about forty minutes, until the filling is golden and set. Serve warm.

Recenzii

New York Times Notable Cookbook of 2011

“a valentine to produce”

—Mother Jones, Favorite Cookbooks of 2011, 12/3/11

“Little about TENDER, British writer Nigel Slater’s quietly epic cookbook about preparing vegetables, feels designed for the American consumer. The author’s preoccupations are so personal, so drawn from the quotidian pleasures of tending his small garden in London, that they feel far removed from the celebrity-penned, diet-driven, ego-tripping cookbooks that dominate U.S. bestseller lists. . . . Slater, in other words, is an obsessive, but one whose obsession seems to stop in the kitchen. Slater has too much respect for all involved — the ingredient, the reader, the joy of discovery in the kitchen — to want to serve as your nanny. He’d rather play your mentor, the kind who wants you to love the messy process, not just the finished dish, which, come to think of it, you’ll love, too. These easy-to-execute dishes go down just as easy. It all makes you look forward to Slater’s second “Tender” volume, dedicated to fruits, due to arrive stateside next spring.”

—The Washington Post, 8/2/11

“Not only is Nigel Slater one of the greatest living food writers, he's also the ultimate urban gardener. His latest book, Tender, just might inspire you to tear up your lawn and get planting.”

—Bon Appétit, August 2011

“A seriously hefty and seriously engaging homage to the garden, from one of Britain’s foremost food authorities.”

—NYTimes.com, Summer Cookbook Roundup, 6/2/11

“Tender is pleasing in so many ways. For cooks it's filled with glorious vegetable-centric recipes, for gardeners it's an insightful and personal story about just how much a garden can mean, and for those who just enjoy reading about food, well, you're going to love getting acquainted with Nigel Slater.”

—Serious Eats, Cook the Book, 5/23/11

“But the crowning glory of "Tender" is Mr. Slater's own prose, even when treating of something as lowly as the autumnal cabbage—each dark-green leaf of which "somehow seems as if it will fend off our winter ills. Elephant ears of crinkled green, sparkling with dew; black plumes of cavolo nero like feathers on a funeral horse, and the dense, ice crisp flesh of red cabbage. Strong flavors indeed." Strong, yes, but also tenderly enticing, as guests at Mr. Slater's latest literary feast will discover.”

—The Wall Street Journal, Bookshelf, 4/23/11

“The best Brit you’ve never heard of. . . . Nigel Slater is who you’d get if you combined Alice Waters with Mark Bittman: a garden-to-table advocate whose goal in life is to make people love fresh produce and cooking because they are – gasp – fabulous and fun and do not have to be fussy in the slightest.”

—The Christian Science Monitor, 4/19/11

“Engagingly written and showcasing more than 200 full-color photos, this attractive and infinitely useful collection shows how to tastefully incorporate more vegetables into one's diet while providing an informative primer on gardening.”

—Starred Review, Publishers Weekly, 3/7/11

“Nigel Slater’s Tender is a rich tale of one man’s passion for cultivating, cooking, and eating from the garden. His sensuous and delicious recipes make us want to run right into the kitchen and start cooking. But even if you never set a foot in your garden or turn on the stove, it is a great, inspiring read.”

—Christopher Hirsheimer and Melissa Hamilton, authors of Canal House Cooking

“As a second-floor city-dweller with no patch of land to call my own, a glimpse into Nigel Slater’s garden sanctuary makes me ache for a small plot of good dirt, preferably just off a kitchen, to grow some of what I eat. Nigel captures the small moments—the rituals, sights, and smells—that are part of the cycle of growing, cooking, eating, and sharing, culminating in a collection of vibrant, bold yet approachable recipes. A rare treasure.”

—Heidi Swanson, author of Super Natural Cooking

“A home garden isn’t just the best source of the ultimately fresh. It’s also the place where scent, smell, and touch vie with taste to inspire and shape our culinary imagination. Nigel Slater, a food writer too little known in this country, has a unique ability to convey this magical play of the senses, and what happens when we let it permeate our cooking. The imaginative, often inspired dishes that result are a revelation. Tender deserves pride of place on any vegetable lover’s shelf.”

—John Thorne, author of Outlaw Cook

“Nigel Slater is my kind of cook. His gently passionate garden-to-kitchen approach shows respect for the beauty of simple ingredients. He celebrates the sweetness of a roasted onion, the thrill of a ripe berry, and the real pleasure of a good salad.”

—David Tanis, author of Heart of the Artichoke

“a valentine to produce”

—Mother Jones, Favorite Cookbooks of 2011, 12/3/11

“Little about TENDER, British writer Nigel Slater’s quietly epic cookbook about preparing vegetables, feels designed for the American consumer. The author’s preoccupations are so personal, so drawn from the quotidian pleasures of tending his small garden in London, that they feel far removed from the celebrity-penned, diet-driven, ego-tripping cookbooks that dominate U.S. bestseller lists. . . . Slater, in other words, is an obsessive, but one whose obsession seems to stop in the kitchen. Slater has too much respect for all involved — the ingredient, the reader, the joy of discovery in the kitchen — to want to serve as your nanny. He’d rather play your mentor, the kind who wants you to love the messy process, not just the finished dish, which, come to think of it, you’ll love, too. These easy-to-execute dishes go down just as easy. It all makes you look forward to Slater’s second “Tender” volume, dedicated to fruits, due to arrive stateside next spring.”

—The Washington Post, 8/2/11

“Not only is Nigel Slater one of the greatest living food writers, he's also the ultimate urban gardener. His latest book, Tender, just might inspire you to tear up your lawn and get planting.”

—Bon Appétit, August 2011

“A seriously hefty and seriously engaging homage to the garden, from one of Britain’s foremost food authorities.”

—NYTimes.com, Summer Cookbook Roundup, 6/2/11

“Tender is pleasing in so many ways. For cooks it's filled with glorious vegetable-centric recipes, for gardeners it's an insightful and personal story about just how much a garden can mean, and for those who just enjoy reading about food, well, you're going to love getting acquainted with Nigel Slater.”

—Serious Eats, Cook the Book, 5/23/11

“But the crowning glory of "Tender" is Mr. Slater's own prose, even when treating of something as lowly as the autumnal cabbage—each dark-green leaf of which "somehow seems as if it will fend off our winter ills. Elephant ears of crinkled green, sparkling with dew; black plumes of cavolo nero like feathers on a funeral horse, and the dense, ice crisp flesh of red cabbage. Strong flavors indeed." Strong, yes, but also tenderly enticing, as guests at Mr. Slater's latest literary feast will discover.”

—The Wall Street Journal, Bookshelf, 4/23/11

“The best Brit you’ve never heard of. . . . Nigel Slater is who you’d get if you combined Alice Waters with Mark Bittman: a garden-to-table advocate whose goal in life is to make people love fresh produce and cooking because they are – gasp – fabulous and fun and do not have to be fussy in the slightest.”

—The Christian Science Monitor, 4/19/11

“Engagingly written and showcasing more than 200 full-color photos, this attractive and infinitely useful collection shows how to tastefully incorporate more vegetables into one's diet while providing an informative primer on gardening.”

—Starred Review, Publishers Weekly, 3/7/11

“Nigel Slater’s Tender is a rich tale of one man’s passion for cultivating, cooking, and eating from the garden. His sensuous and delicious recipes make us want to run right into the kitchen and start cooking. But even if you never set a foot in your garden or turn on the stove, it is a great, inspiring read.”

—Christopher Hirsheimer and Melissa Hamilton, authors of Canal House Cooking

“As a second-floor city-dweller with no patch of land to call my own, a glimpse into Nigel Slater’s garden sanctuary makes me ache for a small plot of good dirt, preferably just off a kitchen, to grow some of what I eat. Nigel captures the small moments—the rituals, sights, and smells—that are part of the cycle of growing, cooking, eating, and sharing, culminating in a collection of vibrant, bold yet approachable recipes. A rare treasure.”

—Heidi Swanson, author of Super Natural Cooking

“A home garden isn’t just the best source of the ultimately fresh. It’s also the place where scent, smell, and touch vie with taste to inspire and shape our culinary imagination. Nigel Slater, a food writer too little known in this country, has a unique ability to convey this magical play of the senses, and what happens when we let it permeate our cooking. The imaginative, often inspired dishes that result are a revelation. Tender deserves pride of place on any vegetable lover’s shelf.”

—John Thorne, author of Outlaw Cook

“Nigel Slater is my kind of cook. His gently passionate garden-to-kitchen approach shows respect for the beauty of simple ingredients. He celebrates the sweetness of a roasted onion, the thrill of a ripe berry, and the real pleasure of a good salad.”

—David Tanis, author of Heart of the Artichoke

Cuprins

Introducion

Asparagus

Beets

Broccoli and the sprouting greens

Brussels sprouts

Cabbage

Carrots

Cauliflower

Celery

Celery root

Chard

The Chinese greens

Eggplants

Fava beans

Jerusalem artichokes

Kale and cavolo nero

Leeks

Onions

Parsnips

Peas

Peppers

Pole beans

Potatoes

Pumpkin and other winter squashes

Rutabaga

Salad leaves

Spinach

Tomatoes

Turnips

Zucchini and other summer squashes

A few other good things

Index

Asparagus

Beets

Broccoli and the sprouting greens

Brussels sprouts

Cabbage

Carrots

Cauliflower

Celery

Celery root

Chard

The Chinese greens

Eggplants

Fava beans

Jerusalem artichokes

Kale and cavolo nero

Leeks

Onions

Parsnips

Peas

Peppers

Pole beans

Potatoes

Pumpkin and other winter squashes

Rutabaga

Salad leaves

Spinach

Tomatoes

Turnips

Zucchini and other summer squashes

A few other good things

Index