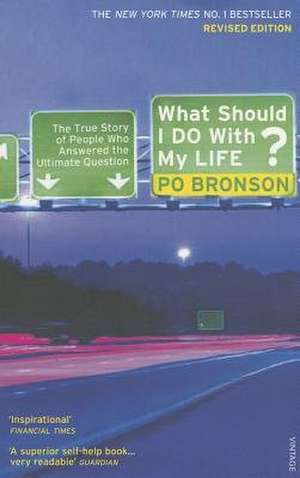

What Should I Do With My Life?

Autor Po Bronsonen Limba Engleză Paperback – 2004

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 57.49 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| BALLANTINE BOOKS – 31 oct 2005 | 57.49 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Vintage Publishing – 2004 | 71.59 lei 23-34 zile | +28.95 lei 6-10 zile |

| Random House Trade – 30 noi 2003 | 136.04 lei 3-5 săpt. |

Preț: 71.59 lei

Preț vechi: 83.91 lei

-15% Nou

Puncte Express: 107

Preț estimativ în valută:

13.70€ • 14.93$ • 11.54£

13.70€ • 14.93$ • 11.54£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 04-15 aprilie

Livrare express 18-22 martie pentru 38.94 lei

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780099437994

ISBN-10: 0099437996

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: ports.

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

ISBN-10: 0099437996

Pagini: 432

Ilustrații: ports.

Dimensiuni: 129 x 198 x 35 mm

Greutate: 0.4 kg

Editura: Vintage Publishing

Locul publicării:United Kingdom

Notă biografică

Po Bronson

Extras

Destiny vs.Self-Created Meaning

An Ordinary Guy

EVEN THE DESTINED STRUGGLE

Wouldn’t it be so much easier if you got a letter in the mail when you were seventeen, signed by someone who had a direct pipeline to Ultimate Meaning, telling you exactly who you are and what your true destiny is? Then you could carry this letter around in your pocket, and when you got confused or distracted and suddenly melted down, you’d reach for your wallet and grab the letter and read it again and go, “Oh, right.”

Well, a friend of mine has such a letter. He’s thirty-two years old and rents a bedroom from a nice lady in Phoenix near the base of Camelback Mountain. He’s gray at the temples, wears Hawaiian shirts, and drives a dusty Oldsmobile that suffers from bad alignment. The car’s tape player is broken, which is fine by me because I can’t stand the soft rock he listens to. He loves America because friends here treat him like an ordinary person. He says being here has made him much more open-minded. He grew up in a refugee camp in southern India. When he got the letter he had just enrolled in a special school there, with the vague notion of eventually becoming a professor of Tibetan literature, though he admits he wasn’t much of a student. But what else was there to do in life? No way was he going to be a farmer. Being a businessman meant having to sell, and he didn’t study hard enough to ever become a doctor. He couldn’t imagine sitting out his life in a government office job, filing forms. His name was Choeaor Dondup, but everyone called him Ali, after the boxer, because he was big. His hair hung to his shoulders. He spent most of his time figuring out how to get into his girlfriend’s pants. He played soccer. He was scared of the dark. Then one day at school he received this letter, signed by the Dalai Lama.

Ali was a big believer in the Dalai Lama.

The letter said he wasn’t Choeaor Dondup after all. Instead, he was the reincarnation of a warrior who, along with his five brothers, had ruled a poor and remote region of eastern Tibet six lifetimes ago. The brothers had descended from one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons. Ali’s Previous One turned his back on the family’s violent rule and became a monk. Over his lifetime he founded thirteen monasteries and became the great spiritual leader of this region, the Tehor. Ali’s real name was Za Rinpoche, which is Tibetan for “The Dharma King.”

Imagine! You’re not a dumb, lost, inexperienced seventeen-year-old! We actually have a

spot picked out for you! And not just any spot!

wanted: Great Spiritual Leader. No experience necessary.

Nevertheless, the letter was a bit of a shock. They wanted him to attend the Drepung monastery in northern India. All Ali could think about was, “Am I going to have to cut my hair?” “Am I going to have to become a monk? Give up sex?” You think it would be easy if your destiny were offered on a silver platter. But Ali went around for a few days openly expressing his angst and annoying his friends by debating whether this was the right thing to do. The social pressure was so great that eventually he shut up, gave in, and went off to the monastery, keeping his doubts to himself. It took four years for the doubts to evaporate. But it’s never been easy. He spent the next twelve years memorizing two-thousand-year-old ancient texts, the whole time craving the kind of understanding that comes from experience. Back in Tehor, when people are dying they hold his photograph inches from their face and stare at him, wanting him to be the last thing they ever see before they cross over into unembodied consciousness. That’s how much faith they have in Rinpoche–more than he has in himself, I suspect.

I found Rinpoche like this: When my son was born, my mom cleaned out her basement and brought up my well-preserved souvenirs from my childhood, soccer trophies and warmup jackets and my high school yearbooks. In one of those yearbooks was a nice note from an upperclasswoman, Jodi, fondly remembering those long conversations we used to have during studio art classes. “What conversations?” I wanted to remember. So I tracked her down, and during another long conversation she mentioned she’d been hanging out with Rinpoche. I was curious, though not for any particular reason. Just curious. Curiosity is a raw and genuine sign from deep inside our tangled psyches, and we’d do well to follow the direction it points us in. So to Jodi I said, “I gotta meet that guy,” and booked tickets to Phoenix.

What would it be like to have this certainty about your place in the world? To have it in writing from the Dalai Lama himself! Of course, my desire to understand this wasn’t my only motivation. I was excited to meet a holy man. Perhaps his spiritual presence might rub off on me, and he might offer me guidance. Instead I found a friend, who, though sacred, was still utterly human and real. He was skilled at minimizing his anguish over everyday struggles, but he still faced them routinely and fought his urges like any of us. Possessing that letter had not relieved him of having to figure out where he really belonged and make some hard choices. In his mind, this question was not settled.

He and I were riding around Phoenix a little while ago, looking for some authentic Mexican food. I was joshing him about this reincarnation thing.

“Come on, you really believe it?”

“Yes.”

“So, all of you, or just, like, your soul?”

He said the biggest misconception in the West, and in young Tibetans, was that mind is physical.

I said, “How do you know young Tibetans? You said you’ve never even been to Tibet.” (China wouldn’t let him into his country.)

“Like, you know, I’ve met many who are also in exile.”

“In Phoenix?”

He said that they were mostly in New York.

“What does that even mean, ‘mind is not physical’? That’s so cryptic.”

He tried to unpack his statement for me. Sanskrit describes five layers of self, or mind:

Physical,

feeling,

perception,

intention,

and consciousness.

His consciousness had been reincarnated, but his perceptions and feelings and body had not. That said, the inner layer, by itself, is no more valid or important than the outer. Self is the combination of the five.

“So on the inside you’ve got it figured out, but the rest of you is dragging along.”

Rinpoche laughed, and it’s when he laughs that he seems so wise. He learned his English in Atlanta from undergrads at Emory University, and he picked up their vocal idiosyncrasies, tossing “kind of,” “like,” and “you know what I mean” into every sentence.

He speaks English like a teenager, but laughs like a man six lifetimes old–such a deep, merry, pure chuckle.

I asked him if Buddhists believe we all get a specific destiny.

“We don’t think there’s a specific place in your life to go. Everybody’s destiny is to become an enlightened being and reach the everlasting state of mind.”

“That’s pretty easy for you to say. Your destiny arrived in the mail. What if you had to go out and get a job?”

He laughed again. “Yes, that I could not imagine.”

Rinpoche has always had to be pushed to take the next step. In 1998, the Dalai Lama chose him to lead a tour of monks across the United States. Rinpoche didn’t want to go. He’d heard the tour required long bus rides, thirteen hours at a time. He relented when the abbot leaned on him. Rinpoche says he was a narrow-minded snob back then. Maybe a monastery sounds like a terrific place to become a deep person, but the truth was, he was sheltered and had a big ego. He didn’t hang out with ordinary monks, only monks of high status. He had no respect for other religions, and assumed anyone who wasn’t a Buddhist couldn’t be a nice person. He was lonely and too serious. But traveling in America did wonders for his personality. After a year, he went back to the Drepung Monastery, and everyone said, “Wow, you’ve changed a lot.” He hung out with monks regardless of their status. He laughed all the time. He felt more grounded. His elders were so impressed they asked him to stay and teach. For once he had the balls to say, “That is not in my nature,” and stick by it. He wanted to return to America, where not everyone treats him like a divine being. He wanted to understand the Western mind, how people in the West think.

Exposing himself to this crazy world was making him into a better person, and that was the right path to be on.

If it were me, no matter how cool or great it would be to have a spiritual calling, and to be given this early in life, I’d still have that American notion of needing to discover things myself. I’d need independence–I’d feel controlled. I might now and then be testy about having my calling put upon me rather than arriving at it by myself. We have mixed feelings about the seductive notion of destiny. There’s a persistent tension between wanting our life’s purpose to be revealed to us by some higher power and wanting to scrap and fight for it against all odds–to earn it without help. We think about destiny sort of like how we feel about inheritance–we covet its fruit but it’s sweeter if we earned it ourselves. And so I wasn’t surprised when Rinpoche called to give me his new address and phone number.

“What happened?”

“I am not with Bodhiheart anymore.” Bodhiheart was the foundation he cofounded with his sponsor–the woman in whose house he had lived until now.

“Did you get in a fight?”

“Uh, not really. Kind of. I myself am not a citizen, you know? So as my sponsor, I relied on her for legal things like this.”

“Like creating the foundation.”

“That is right. So I have my own foundation now.” He let out a hearty laugh, his punch line coming a little quick before I could understand.

“What happened between you?”

“I felt she tried to keep people from me, control my schedule, these things, you know? Like she wanted to be the access to me. Like last time you were here? She was upset with that.”

“But you’re my friend!”

He sighed. “That is right. You understand.”

“You don’t want anyone to control you.”

“That is right.”

“So have you ever lived alone before?” He’d spent most of his life in a monastery with four thousand monks.

“No, never.”

“Can you cook?”

“Simple things.”

“Going out for burritos a lot, I bet.”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“How big is your apartment?”

“Not too small.”

“You’re not still scared of the dark, are you?”

Rinpoche laughed.

“I’m glad you’re learning to look out for yourself,” I said.

“Yes. At this I am getting better.”

Once he’d said to me, “I wish I could be ordinary sometimes.” He was getting his chance.

At one of Rinpoche’s “teachings” at a hospice, he described how fears hold us back from our own advancement. “Fear is like a wound within our emotions,” he said. You heal a fear much like you heal a cut on your hand. If you ignore a cut on your hand, it will get infected. But it will heal itself if you pay attention to it and give it time. Same with a fear.

First, recognize its existence–what kind of fear is it? Is it fear of poverty, of loneliness, of rejection? Then use common sense. Don’t let the fear get infected. Often we burn 70 percent of our emotional energy on what we fear might happen (90 percent of which won’t happen). By devoting our energy to our other emotions, we will heal naturally.

This didn’t sink in for me right away. In the moment, my mind tagged it as “deep,” and filed it away to be revisited later. Which I did. When my way of organizing this book was finally coming into focus–as stories portraying people working through their fears and misconceptions–that method rang a bell. I dug up my notes on Rinpoche’s teaching and found the similarity. I felt like I’d wasted time getting there the hard way. “Look, it took me nine months to figure this out by myself, when all along Rinpoche was trying to show me this is how to do it.” But, then again, I felt like I understood it better because I’d done it the hard way.

Which was how he’d lived, too. His purpose was given to him, but he’d had to go find it anyway.

From the Hardcover edition.

An Ordinary Guy

EVEN THE DESTINED STRUGGLE

Wouldn’t it be so much easier if you got a letter in the mail when you were seventeen, signed by someone who had a direct pipeline to Ultimate Meaning, telling you exactly who you are and what your true destiny is? Then you could carry this letter around in your pocket, and when you got confused or distracted and suddenly melted down, you’d reach for your wallet and grab the letter and read it again and go, “Oh, right.”

Well, a friend of mine has such a letter. He’s thirty-two years old and rents a bedroom from a nice lady in Phoenix near the base of Camelback Mountain. He’s gray at the temples, wears Hawaiian shirts, and drives a dusty Oldsmobile that suffers from bad alignment. The car’s tape player is broken, which is fine by me because I can’t stand the soft rock he listens to. He loves America because friends here treat him like an ordinary person. He says being here has made him much more open-minded. He grew up in a refugee camp in southern India. When he got the letter he had just enrolled in a special school there, with the vague notion of eventually becoming a professor of Tibetan literature, though he admits he wasn’t much of a student. But what else was there to do in life? No way was he going to be a farmer. Being a businessman meant having to sell, and he didn’t study hard enough to ever become a doctor. He couldn’t imagine sitting out his life in a government office job, filing forms. His name was Choeaor Dondup, but everyone called him Ali, after the boxer, because he was big. His hair hung to his shoulders. He spent most of his time figuring out how to get into his girlfriend’s pants. He played soccer. He was scared of the dark. Then one day at school he received this letter, signed by the Dalai Lama.

Ali was a big believer in the Dalai Lama.

The letter said he wasn’t Choeaor Dondup after all. Instead, he was the reincarnation of a warrior who, along with his five brothers, had ruled a poor and remote region of eastern Tibet six lifetimes ago. The brothers had descended from one of Genghis Khan’s grandsons. Ali’s Previous One turned his back on the family’s violent rule and became a monk. Over his lifetime he founded thirteen monasteries and became the great spiritual leader of this region, the Tehor. Ali’s real name was Za Rinpoche, which is Tibetan for “The Dharma King.”

Imagine! You’re not a dumb, lost, inexperienced seventeen-year-old! We actually have a

spot picked out for you! And not just any spot!

wanted: Great Spiritual Leader. No experience necessary.

Nevertheless, the letter was a bit of a shock. They wanted him to attend the Drepung monastery in northern India. All Ali could think about was, “Am I going to have to cut my hair?” “Am I going to have to become a monk? Give up sex?” You think it would be easy if your destiny were offered on a silver platter. But Ali went around for a few days openly expressing his angst and annoying his friends by debating whether this was the right thing to do. The social pressure was so great that eventually he shut up, gave in, and went off to the monastery, keeping his doubts to himself. It took four years for the doubts to evaporate. But it’s never been easy. He spent the next twelve years memorizing two-thousand-year-old ancient texts, the whole time craving the kind of understanding that comes from experience. Back in Tehor, when people are dying they hold his photograph inches from their face and stare at him, wanting him to be the last thing they ever see before they cross over into unembodied consciousness. That’s how much faith they have in Rinpoche–more than he has in himself, I suspect.

I found Rinpoche like this: When my son was born, my mom cleaned out her basement and brought up my well-preserved souvenirs from my childhood, soccer trophies and warmup jackets and my high school yearbooks. In one of those yearbooks was a nice note from an upperclasswoman, Jodi, fondly remembering those long conversations we used to have during studio art classes. “What conversations?” I wanted to remember. So I tracked her down, and during another long conversation she mentioned she’d been hanging out with Rinpoche. I was curious, though not for any particular reason. Just curious. Curiosity is a raw and genuine sign from deep inside our tangled psyches, and we’d do well to follow the direction it points us in. So to Jodi I said, “I gotta meet that guy,” and booked tickets to Phoenix.

What would it be like to have this certainty about your place in the world? To have it in writing from the Dalai Lama himself! Of course, my desire to understand this wasn’t my only motivation. I was excited to meet a holy man. Perhaps his spiritual presence might rub off on me, and he might offer me guidance. Instead I found a friend, who, though sacred, was still utterly human and real. He was skilled at minimizing his anguish over everyday struggles, but he still faced them routinely and fought his urges like any of us. Possessing that letter had not relieved him of having to figure out where he really belonged and make some hard choices. In his mind, this question was not settled.

He and I were riding around Phoenix a little while ago, looking for some authentic Mexican food. I was joshing him about this reincarnation thing.

“Come on, you really believe it?”

“Yes.”

“So, all of you, or just, like, your soul?”

He said the biggest misconception in the West, and in young Tibetans, was that mind is physical.

I said, “How do you know young Tibetans? You said you’ve never even been to Tibet.” (China wouldn’t let him into his country.)

“Like, you know, I’ve met many who are also in exile.”

“In Phoenix?”

He said that they were mostly in New York.

“What does that even mean, ‘mind is not physical’? That’s so cryptic.”

He tried to unpack his statement for me. Sanskrit describes five layers of self, or mind:

Physical,

feeling,

perception,

intention,

and consciousness.

His consciousness had been reincarnated, but his perceptions and feelings and body had not. That said, the inner layer, by itself, is no more valid or important than the outer. Self is the combination of the five.

“So on the inside you’ve got it figured out, but the rest of you is dragging along.”

Rinpoche laughed, and it’s when he laughs that he seems so wise. He learned his English in Atlanta from undergrads at Emory University, and he picked up their vocal idiosyncrasies, tossing “kind of,” “like,” and “you know what I mean” into every sentence.

He speaks English like a teenager, but laughs like a man six lifetimes old–such a deep, merry, pure chuckle.

I asked him if Buddhists believe we all get a specific destiny.

“We don’t think there’s a specific place in your life to go. Everybody’s destiny is to become an enlightened being and reach the everlasting state of mind.”

“That’s pretty easy for you to say. Your destiny arrived in the mail. What if you had to go out and get a job?”

He laughed again. “Yes, that I could not imagine.”

Rinpoche has always had to be pushed to take the next step. In 1998, the Dalai Lama chose him to lead a tour of monks across the United States. Rinpoche didn’t want to go. He’d heard the tour required long bus rides, thirteen hours at a time. He relented when the abbot leaned on him. Rinpoche says he was a narrow-minded snob back then. Maybe a monastery sounds like a terrific place to become a deep person, but the truth was, he was sheltered and had a big ego. He didn’t hang out with ordinary monks, only monks of high status. He had no respect for other religions, and assumed anyone who wasn’t a Buddhist couldn’t be a nice person. He was lonely and too serious. But traveling in America did wonders for his personality. After a year, he went back to the Drepung Monastery, and everyone said, “Wow, you’ve changed a lot.” He hung out with monks regardless of their status. He laughed all the time. He felt more grounded. His elders were so impressed they asked him to stay and teach. For once he had the balls to say, “That is not in my nature,” and stick by it. He wanted to return to America, where not everyone treats him like a divine being. He wanted to understand the Western mind, how people in the West think.

Exposing himself to this crazy world was making him into a better person, and that was the right path to be on.

If it were me, no matter how cool or great it would be to have a spiritual calling, and to be given this early in life, I’d still have that American notion of needing to discover things myself. I’d need independence–I’d feel controlled. I might now and then be testy about having my calling put upon me rather than arriving at it by myself. We have mixed feelings about the seductive notion of destiny. There’s a persistent tension between wanting our life’s purpose to be revealed to us by some higher power and wanting to scrap and fight for it against all odds–to earn it without help. We think about destiny sort of like how we feel about inheritance–we covet its fruit but it’s sweeter if we earned it ourselves. And so I wasn’t surprised when Rinpoche called to give me his new address and phone number.

“What happened?”

“I am not with Bodhiheart anymore.” Bodhiheart was the foundation he cofounded with his sponsor–the woman in whose house he had lived until now.

“Did you get in a fight?”

“Uh, not really. Kind of. I myself am not a citizen, you know? So as my sponsor, I relied on her for legal things like this.”

“Like creating the foundation.”

“That is right. So I have my own foundation now.” He let out a hearty laugh, his punch line coming a little quick before I could understand.

“What happened between you?”

“I felt she tried to keep people from me, control my schedule, these things, you know? Like she wanted to be the access to me. Like last time you were here? She was upset with that.”

“But you’re my friend!”

He sighed. “That is right. You understand.”

“You don’t want anyone to control you.”

“That is right.”

“So have you ever lived alone before?” He’d spent most of his life in a monastery with four thousand monks.

“No, never.”

“Can you cook?”

“Simple things.”

“Going out for burritos a lot, I bet.”

“Yes, that’s right.”

“How big is your apartment?”

“Not too small.”

“You’re not still scared of the dark, are you?”

Rinpoche laughed.

“I’m glad you’re learning to look out for yourself,” I said.

“Yes. At this I am getting better.”

Once he’d said to me, “I wish I could be ordinary sometimes.” He was getting his chance.

At one of Rinpoche’s “teachings” at a hospice, he described how fears hold us back from our own advancement. “Fear is like a wound within our emotions,” he said. You heal a fear much like you heal a cut on your hand. If you ignore a cut on your hand, it will get infected. But it will heal itself if you pay attention to it and give it time. Same with a fear.

First, recognize its existence–what kind of fear is it? Is it fear of poverty, of loneliness, of rejection? Then use common sense. Don’t let the fear get infected. Often we burn 70 percent of our emotional energy on what we fear might happen (90 percent of which won’t happen). By devoting our energy to our other emotions, we will heal naturally.

This didn’t sink in for me right away. In the moment, my mind tagged it as “deep,” and filed it away to be revisited later. Which I did. When my way of organizing this book was finally coming into focus–as stories portraying people working through their fears and misconceptions–that method rang a bell. I dug up my notes on Rinpoche’s teaching and found the similarity. I felt like I’d wasted time getting there the hard way. “Look, it took me nine months to figure this out by myself, when all along Rinpoche was trying to show me this is how to do it.” But, then again, I felt like I understood it better because I’d done it the hard way.

Which was how he’d lived, too. His purpose was given to him, but he’d had to go find it anyway.

From the Hardcover edition.

Recenzii

“Beautifully written ... Free of religiosity and cant, the book also is remarkably spiritual.... Bronson masterfully blends narrative and interpretation, coaxing his subjects to life in telling, resonant anecdotes. This is holistic writing of unique, encouraging power.”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“This new title matches a worthwhile premise—the question of how we each find our personal mission in life—with a tone refreshingly free of either sap or cynicism.... What [Bronson] finds is equally useful to middle-age folks and fresh college grads.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer, “Year’s Best Books”

—The Atlanta Journal-Constitution

“This new title matches a worthwhile premise—the question of how we each find our personal mission in life—with a tone refreshingly free of either sap or cynicism.... What [Bronson] finds is equally useful to middle-age folks and fresh college grads.”

—Cleveland Plain Dealer, “Year’s Best Books”