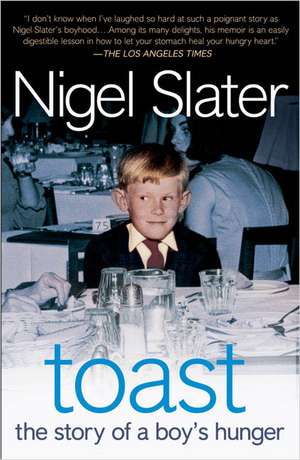

Toast

Autor Nigel Slateren Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 oct 2005

His mother was a chops-and-peas sort of cook, exasperated by the highs and lows of a temperamental stove, a finicky little son, and the asthma that was to prove fatal. His father was a honey-and-crumpets man with an unpredictable temper. When Nigel’s widowed father takes on a housekeeper with social aspirations and a talent in the kitchen, the following years become a heartbreaking cooking contest for his father’s affections. But as he slowly loses the battle, Nigel finds a new outlet for his culinary talents, and we witness the birth of what was to become a lifelong passion for food. Nigel’s likes and dislikes, aversions and sweet-toothed weaknesses, form a fascinating backdrop to this exceptionally moving memoir of childhood, adolescence, and sexual awakening.

A bestseller (more than 300,000 copies sold) and award-winner in the UK, Toast is sure to delight both foodies and memoir readers on this side of the pond—especially those who made such enormous successes of Ruth Reichl’s Tender at the Bone and Anthony Bourdain’s Kitchen Confidential.

| Toate formatele și edițiile | Preț | Express |

|---|---|---|

| Paperback (3) | 69.04 lei 3-5 săpt. | +6.99 lei 4-10 zile |

| HarperCollins Publishers – 16 apr 2004 | 69.04 lei 3-5 săpt. | +6.99 lei 4-10 zile |

| GOTHAM BOOKS – 31 aug 2011 | 131.34 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Penguin Adult Hc/Tr – 6 oct 2005 | 136.52 lei 3-5 săpt. | |

| Hardback (1) | 107.96 lei 3-5 săpt. | +15.33 lei 4-10 zile |

| HarperCollins Publishers – 17 aug 2023 | 107.96 lei 3-5 săpt. | +15.33 lei 4-10 zile |

Preț: 136.52 lei

Nou

26.12€ • 27.34$ • 21.74£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 10-24 martie

Specificații

ISBN-10: 1592401619

Pagini: 256

Dimensiuni: 135 x 203 x 15 mm

Greutate: 0.33 kg

Editura: Penguin Adult Hc/Tr

Recenzii

ߝThe New York Times

"Many scenes are hilarious and the language is so evocative that it will stimulate your own fond remembrance of meals past."

ߝPeople

"At its sweet heart, *Toast is a stirring tale of a troubled childhood, strung together by memorable meals both appetizing and revolting."

--Entertainment Weekly

"Using prosaic touchstones like milk skin, tinned fruit, and bad apple crumble, Slater recounts his harsh coming-of-age in [...] unsauced sentences. *Toast will leave you with a newfound belief that chef Jamie Oliver, who has proclaimed Slater a genius, has good taste in more than just arugula."

--Elle

"Nigel is a genius."

ߝJamie Oliver, author of Jamie’s Kitchen, The Naked Chef, and Happy Days with the Naked Chef

Notă biografică

Extras

“Write a piece about the food of your childhood, will you?” asked the (then) editor of my weekly food column in London’s Observer newspaper. I liked the idea and went out and bought the candies and puddings that, some thirty years ago, had been such an important part of my diet. Some I still ate as an occasional treat; others I had not had my tongue around for twenty years or more. As I unwrapped each sticky chocolate bar or sucked each brightly colored candy, the memories—surprisingly clear and loud—flooded back. This would be easy, I thought. A painless column to write after several years of penning weekly recipe-led pieces. At first it was all straightforward enough. Oat cookies reminded me of coming home from school; green beans brought back the smell of the farm were I was sent to pick them; Turkish Delight reminded me of Christmas. In that respect it was not dissimilar from other foodie memoirs. But the more I ate the more I realized that not every mouthful produced a memory so sweet. A dish of canned raspberries revisited a violent thrashing from my father that brought me to a point of near collapse (I had spilt them and their scarlet juice on the new gray carpet, and he was distraught from being newly widowed); cream-filled Walnut Whips hit back with an embarrassingly vivid recall of early sexual voyeurism; and the soft pink marshmallows I had not eaten since I was nine I found to be inseparably linked with my late mom’s goodnight kisses.

I decided to take a chance and made the piece uninhibitedly personal. I linked the food not just with events but with feelings, warts and all, and even chucked in a fair helping of sex. I handed the column in.

A half hour later the phone rang. I knew it was my editor even before I picked it up. “It’s about the story,” she said. Immediately I gabbled at her, saying that I was sorry, I knew it was too intimate and was out of style. I offered to rewrite it, taking out all the memoir and sticking strictly to the food. “No,” she insisted, “I love it. I’m going to publish it exactly as it is.”

The morning after the piece, now called “My Life on a Plate,” came out, Louise Haines, my literary editor who had worked on all of my cookbooks, called to say that she had read the story and thought I should write it as a book. We were in the depths of finishing Real Food, my fifth cookbook and one that tied into my television cooking series at the time. Overloaded with work, we put the idea of the memoir on the back burner.

Forget salt and pepper, garlic and lemon. The most successful seasoning for what we eat is a good pinch of nostalgia. Ask anyone about the foods they grew up with and you will unleash a torrent of (mostly) happy memories. I must admit that I knew this when I finally set out to write Toast. To punctuate the story of a childhood memoir with brand names of the chocolate and candy and recipes that were household names at the time would be sure to ring a few bells.

I suppose it is perfectly appropriate that I should have chosen food as the blood in my memoir’s veins. I have always worked with the stuff; first in restaurant kitchens, and then as a food writer. I have had a weekly newspaper cooking column for over a decade, written for glossy magazines, and have published several cookbooks, the first of which, Real Fast Food, is now in its twenty-eighth printing. Food has been my career, my hobby, and, it must be said, my escape.

Yet most people were more than a little surprised that I should write such a personal book at all. Despite my work being well known in the UK, I had never taken (and never will take) the celebrity route. I had devoutly refused to play the game, to attend food symposiums, join writers’ guilds, present cooking demonstrations, or do the cooking circuit. I would go to any length to avoid a photo shoot or a seminar and would rather eat feathers than attend an awards ceremony. Even when I was up for a medal.

There were times, especially toward the end of writing, when I questioned the appropriateness of such a project. When a cooking writer pens his autobiography it is invariably written with a freshly baked, rosy glow. Tales of baking at their mother’s knee is what is expected. Then there is the obligatory early morning trip to the market with your wicker basket complete with vignettes of the woman at the charming little cheese stall and going home with a laden basket and a crusty French loaf. Yet I had not written about any of that. I had waxed lyrical not about the vast cups of steaming café au lait and light-as-a-feather croissants, but of the canned meat pies my father unsuccessfully attempted to bake; the fried eggs with which I was force-fed until I vomited; and the cookbooks that, as an adolescent, I used in lieu of pornography. At one point in the book, more food seemed to come up rather than go down. In addition to that, the manuscript was tinged with sadness. Both my editor and my agent, the only two people to see the then-unfinished manuscript, admitted they had both been brought to tears.

Perhaps I should take the “chocolate-chip-cookie memoir” route instead? And there was another salient point. Why would anyone who worked so hard at keeping a low profile and preserving their privacy choose to write a book that could, at the very least, be described as “intimate”? Revelations, indiscretions, and recollections that even my most devout supporters might file under “too much information.” I don’t know what made me finish it. All I know is that I did.

True to plan, when the book finally came out I was not entirely surprised that so much of the food involved in my upbringing brought back memories for others. What I had not expected was the level of recognition of the backbone of my story. The tale behind the food. What I thought was a singularly personal account of a childhood scarred by the death of a parent, the imposition of a seemingly cruel step-mother, the feelings of frustration, exclusion, loneliness, and even sexual confusion, turned out to be anything but. Letters dropped through my mailbox, newspapers pressed for interviews (though rarely got them), people regularly stopped me apologetically in the street. “I’m sorry, but you have written about my childhood!” . . . “It is as if you were there at my side.” . . . “I had thought I was the only one.” . . . they all said. It quickly dawned on me that Toast had set a thousand bells ringing.

The book was neat and small, like a slice of toast itself. The critics were kind and generous, more so than I could ever have dreamed of, and unlike the cookbooks that had come before, the reviews of Toast appeared on the literary pages. It made the bestseller lists and stayed there for several weeks; then there was a flurry of inquiries about the film rights and they were eventually sold. I was amazed, delighted, and more than a little embarrassed.

When my agent told me that my little book was to be published in the United States I asked simply, “Will it work there?” I was convinced the brand names, the food references, and, in some way, the lifestyle of middle-class England may seem unfamiliar and distant. After all, few American readers had heard of me. I was hardly Julia Child. And then I remembered the first letter that popped through my door after Toast hit the stores in England. The one that said, “I am a lot younger than you, and we obviously come from different backgrounds. Yet in so many ways we appear to have the same childhood. It is like you have written my story.”

-Nigel Slater

London, 2004

Toast 1

My mother is scraping a piece of burned toast out of the kitchen window, a crease of annoyance across her forehead. This is not an occasional occurrence, a once-in-a-while hiccup in a busy mother’s day. My mother burns the toast as surely as the sun rises each morning. In fact, I doubt if she has ever made a round of toast in her life that failed to fill the kitchen with plumes of throat-catching smoke. I am nine now and have never seen butter without black bits in it.

It is impossible not to love someone who makes toast for you. People’s failings, even major ones such as when they make you wear short trousers to school, fall into insignificance as your teeth break through the rough, toasted crust and sink into the doughy cushion of white bread underneath. Once the warm, salty butter has hit your tongue, you are smitten. Putty in their hands.

Christmas Cake

Mum never was much of a cook. Meals arrived on the table as much by happy accident as by domestic science. She was a chops-and-peas sort of a cook, occasionally going so far as to make a rice pudding, exasperated by the highs and lows of a temperamental cream- and-black Aga and a finicky little son. She found it all a bit of an ordeal, and wished she could have left the cooking, like the washing, ironing, and dusting, to Mrs. P., her “woman what does.”

Once a year there were Christmas puddings and cakes to be made. They were made with neither love nor joy. They simply had to be done. “I suppose I had better DO THE CAKE,” she would sigh. The food mixer—she was not the sort of woman to use her hands—was an ancient, heavy Kenwood that lived in a deep, secret hole in the kitchen work surface. My father had, in a rare moment of do-it-yourselfery, fitted a heavy industrial spring under the mixer so that when you lifted the lid to the cupboard the mixer slowly rose like a corpse from a coffin. All of which was slightly too much for my mother, my father’s quaint Heath Robinson craftsmanship taking her by surprise every year, the huge mixer bouncing up like a jack-in-the-box and making her clap her hands to her chest. “Oh heck!” she would gasp. It was the nearest my mother ever got to swearing.

She never quite got the hang of the mixer. I can picture her now, desperately trying to harness her wayward Kenwood, bits of cake mixture flying out of the bowl like something from an I Love Lucy sketch. The cake recipe was written in green biro on a piece of blue Basildon Bond and was kept, crisply folded into four, in the spineless Aga Cookbook that lived for the rest of the year in the bowl of the mixer. The awkward, though ingenious, mixer cupboard was impossible to clean properly, and in among the layers of flour and icing sugar lived tiny black flour weevils. I was the only one who could see them darting around. None of which, I suppose, mattered if you were making Christmas pudding, with its gritty currants and hours of boiling. But this was cake.

Cooks know to butter and line the cake tins before they start the creaming and beating. My mother would remember just before she put the final spoonful of brandy into the cake mixture, then take half an hour to find them. They always turned up in a drawer, rusty and full of fluff. Then there was the annual scrabble to find the brown paper, the scissors, the string. However much she hated making the cake we both loved the sound of the raw cake mixture falling into the tin. “Shhh, listen to the cake mixture,” she would say, and the two of us would listen to the slow plop of the dollops of fruit and butter and sugar falling into the paper-lined cake tin. The kitchen would be warmer than usual and my mother would have that I’ve-just-baked-a-cake glow. “Oh, put the gram on, will you, dear? Put some carols on,” she would say as she put the cake in the top oven of the Aga. Carols or not, it always sank in the middle. The embarrassing hollow, sometimes as deep as your fist, having to be filled in with marzipan.

Forget scented candles and freshly brewed coffee. Every home should smell of baking Christmas cake. That, and warm freshly ironed tea towels hanging on the rail in front of the Aga. It was a pity we had Auntie Fanny living with us. Her incontinence could take the edge off the smell of a chicken curry, let alone a baking cake. No matter how many mince pies were being made, or pine logs burning in the grate, or how many orange-and- clove pomanders my mother had made, there was always the faintest whiff of Auntie Fanny.

Warm sweet fruit, a cake in the oven, woodsmoke, warm ironing, hot retriever curled up by the Aga, mince pies, Mum’s 4711. Every child’s Christmas memories should smell like that. Mine did. It is a pity that there was always a passing breeze of ammonia. Cake holds a family together. I really believed it did. My father was a different man when there was cake in the house. Warm. The sort of man I wanted to hug rather than shy away from. If he had a plate of cake in his hand I knew it would be all right to climb up onto his lap. There was something about the way my mother put a cake on the table that made me feel that all was well. Safe. Secure. Unshakable. Even when she got to the point where she carried her Ventolin inhaler in her left hand all the time. Unshakable. Even when she and my father used to go for long walks, walking ahead of me and talking in hushed tones and he would come back with tears in his eyes.

When I was eight my mother’s annual attempt at icing the family Christmas cake was handed over to me. “I’ve had enough of this lark, dear, you’re old enough now.” She had started to sit down a lot. I made only marginally less of a mess than she did, but at least I didn’t cover the table, the floor, the dog with icing sugar. To be honest, it was a relief to get it out of her hands. I followed the Slater house style of snowy peaks brought up with the flat of a knife and a red ribbon. Even then I wasn’t one to rock the boat. The idea behind the wave effect of her icing was simply to hide the fact that her attempt at covering the cake in marzipan resembled nothing more than an unmade bed. Folds and lumps, creases and tears. A few patches stuck on with a bit of apricot jam.

I knew I could have probably have flat-iced a cake to perfection, but to have done so would have hurt her feelings. So waves it was. There was also a chipped Father Christmas, complete with a jagged lump of last year’s marzipan around his feet, and the dusty bristle tree with its snowy tips of icing. I drew the line at the fluffy yellow Easter chick.

Baking a cake for your family to share, the stirring of cherries, currants, raisins, peel and brandy, brown sugar, butter, eggs, and flour, for me the ultimate symbol of a mother’s love for her husband and kids, was reduced to something that “simply has to be done.” Like cleaning the loo or polishing the shoes. My mother knew nothing of putting glycerine in with the sugar to keep the icing soft, so her rock-hard cake was always the butt of jokes for the entire Christmas. My father once set about it with a hammer and chisel from the shed. So the sad, yellowing cake sat around until about the end of February, the dog giving it the occasional lick as he passed, until it was thrown, much to everyone’s relief, onto the lawn for the birds.

Bread-and-Butter Pudding

My mother is buttering bread for England. The vigor with which she slathers soft yellow fat onto thinly sliced white pap is as near as she gets to the pleasure that is cooking for someone you love. Right now she has the bread knife in her hand and nothing can stop her. She always buys unwrapped, unsliced bread, a pale sandwich loaf without much of a crust, and slices it by hand.

My mother’s way of slicing and buttering has both an ease and an awkwardness about it. She has softened the butter on the back of the Aga so that it forms a smooth wave as the butter knife is drawn across it. She spreads the butter onto the cut side of the loaf, then picks up the bread knife and takes off the buttered slice. She puts down the bread knife, picks up the butter knife, and again butters the freshly cut side of the loaf. She carries on like this till she has used three-quarters of the loaf. The rest she will use in the morning, for toast.

The strange thing is that none of us really eats much bread and butter. It’s like some ritual of good housekeeping that my mother has to go through. As if her grandmother’s dying words had been “always make sure they have enough bread and butter on the table.” No one ever sees what she does with all the slices we don’t eat.

I mention all the leftover bread and butter to Mrs. Butler, a kind, gentle woman whose daughter is in my class at school and whose back garden has a pond with newts and goldfish, crowns of rhubarb, and rows of potatoes. A house that smells of apple crumble. I visit her daughter Madeleine at lunchtime and we often walk back to school together. Mrs. Butler lets me wait while Madeleine finishes her lunch.

“Well, your mum could make bread-and-butter pudding, apple charlotte, eggy bread, or bread pudding,” suggests Mrs. Butler, “or she could turn them into toasted cheese sandwiches.”

I love bread-and-butter pudding. I love its layers of sweet, quivering custard, juicy raisins, and puffed, golden crust. I love the way it sings quietly in the oven; the way it wobbles on the spoon.

You can’t smell a hug. You can’t hear a cuddle. But if you could, I reckon it would smell and sound of warm bread-and-butter pudding.

Sherry Trifle

My father wore old, rust-and-chocolate checked shirts and smelled of sweetbriar tobacco and potting compost. A warm and twinkly-eyed man, the sort who would let his son snuggle up with him in an armchair and fall asleep in the folds of his shirt. “You’ll have to get off now, my leg’s gone to sleep,” he would grumble, and turf me off onto the rug. He would pull silly faces at every opportunity, especially when there was a camera or other children around. Sometimes they would make me giggle, but other times, like when he pulled his monkey face, they scared me so much I used to get butterflies in my stomach.

His clothes were old and soft, which made me want to snuggle up to him even more. He hated wearing new. My father always wore old, heavy brogues and would don a tie even in his greenhouse. He read the Telegraph and Reader’s Digest. A crumpets-and-honey sort of a man with a tight little moustache. God, he had a temper though. Sometimes he would go off, “crack,” like a shotgun. Like when he once caught me going through my mother’s handbag, looking for barley sugars, or when my mother made a batch of twelve fairy cakes and I ate six in one go.

My father never went to church, but said his prayers nightly kneeling by his bed, his head resting in his hands. He rarely cursed, apart from calling people “silly buggers.” I remember he had a series of crushes on singers. First, it was Kathy Kirby, although he once said she was a “bit ritzy,” and then Petula Clark. Sometimes he would buy their records and play them on Sundays after I had listened to my one and only record—a scratched forty-five of Tommy Steele singing “Little White Bull.” The old man was inordinately fond of his collection of female vocals. You should have seen the tears the day Alma Cogan died.

The greenhouse was my father’s sanctuary. I was never sure whether it smelled of him or he smelled of it. In winter, before he went to bed, he would go out and light the old paraffin stove that kept his precious begonias and tomato plants alive. I remember the dark night the stove blew out and the frost got his begonias. He would spend hours down there. I once caught him in the greenhouse with his dick in his hand. He said he was just “going for a pee. It’s good for the plants.” It was different, bigger than it looked in the bath and he seemed to be having a bit of a struggle getting it back into his trousers. He had a bit of a thing about sherry trifle. That and his dreaded leftover turkey stew were the only two recipes he ever made. The turkey stew, a Boxing Day trauma for everyone concerned, varied from year to year, but the trifle had rules. He used ready-made Swiss rolls. The sort that come so tightly wrapped in cellophane you can never get them out without denting the sponge. They had to be filled with raspberry jam, never apricot because you couldn’t see the swirl of jam through the glass bowl the way you could with raspberry. There was much giggling over the sherry bottle. What is it about men and booze? They only cook twice a year but it always involves a bottle of something. Next, a tin of peaches with a little of their syrup. He was meticulous about soaking the sponge roll. First the sherry, then the syrup from the peaches tin. Then the jelly. To purists the idea of jelly in trifle is anathema. But to my father it was essential. If my father’s trifle was human it would be a clown. One of those with striped pants and a red nose. He would make bright yellow custard, Bird’s from a tin. This he smoothed over the jelly, taking an almost absurd amount of care not to let the custard run between the Swiss roll slices and the glass. A matter of honor no doubt.

Once it was cold, the custard was covered with whipped cream, glacé cherries, and whole, blanched almonds. Never silver balls, which he thought common, or chocolate vermicelli, which he thought made it sickly. Just big fat almonds. He never toasted them, even though it would have made them taste better. In later years my stepmother was to suggest a sprinkling of multicolored hundreds and thousands. She might as well have suggested changing his daily paper to the Mirror.

The entire Christmas stood or fell according to the noise the trifle made when the first massive, embossed spoon was lifted out. The resulting noise, a sort of squelch-fart, was like a message from God. A silent trifle was a bad omen. The louder the trifle parped, the better Christmas would be. Strangely, Dad’s sister felt the same way about jelly—making it stronger than usual just so it would make a noise that, even at her hundredth birthday tea, would make the old bird giggle.

You wouldn’t think a man who smoked sweet, scented tobacco, grew pink begonias, and made softly-softly trifle could be scary. His tempers, his rages, his scoldings scared my mother, my brothers, the gardener, even the sweet milkman who occasionally got the order wrong. Once, when I had been caught not brushing my teeth before going to bed, his glare was so full of fire, his face so red and bloated, his hand raised so high that I pissed in my pajamas, right there on the landing outside my bedroom. For all his soft shirts and cuddles and trifles I was absolutely terrified of him.

The Cookbook

The bookcase doubled as a drinks cabinet. Or perhaps that should be the other way around. Three glass decanters with silver labels hanging around their necks boasted Brandy, Whisky, and Port, though I had never known anything in them, not even at Christmas. Dad’s whisky came from a bottle, Dimple Haig, that he kept in a hidden cupboard at the back of the bookcase where he also kept his Canada Dry and a jar of maraschino cherries for when we all had snowballs at Christmas. The front of the drinks cabinet housed his entire collection of books.

The family’s somewhat diminutive library had leatherette bindings and bore Reader’s Digest or The Folio Society on their spines. Most were in mint condition, and invariably “condensed” or “abridged.” Six or so of the books were kept in the cupboard at the back, with the Dimple Haig and a bottle of advocaat; a collection of stories by Edgar Allan Poe, a dog-eared Raymond Chandler, a Philip Roth, and a neat pile of National Geographics. There was also a copy of Marguerite Patten’s All Color Cookbook.

It was a tight fit in between the wall and the back of the bookcase. Dad just opened the door and leaned in to get his whisky; it was more difficult for me to get around there, to wriggle into a position where I could squat in secret and turn the pages of the hidden books. I don’t know how Marguerite Patten would feel knowing that she was kept in the same cupboard as Portnoy’s Complaint, or that I would flip excitedly from one to the other. I hope my father never sells them. “For sale, one copy each of Marguerite Patten’s All Color Cookery and Philip Roth’s Portnoy’s Complaint, first edition, d/w, slightly stained.”

“I don’t know what you want to look at that for,” said Mum once, coming home early and catching me gazing at a photograph of Gammon Steaks with Pineapple and Cherries. “It’s all very fancy, I can’t imagine who cooks like that.” There was duck à l’orange and steak- and-kidney pudding, fish pie, beef Wellington and rock cakes, fruit flan and crème caramel. There was page after page of glorious photographs of stuffed eggs, sole with grapes, and a crown roast of lamb with peas and baby carrots around the edge, parsley sprigs, radish roses, cucumber curls. Day after day I would squeeze around and pore over the recipes fantasizing over Marguerite’s deviled kidneys and Spanish chicken, her prawn cocktail and sausage rolls. Just as I would spend quite a while fantasizing over Portnoy’s way with liver.

The Lunch Box

Josh, Mum and Dad’s new gardener, was cool. He had a black motorbike, a Triumph something or other, and used to bring his lunch neatly packed in a tin box. He licked his cigarette papers, tiny things with barely a pinch of tobacco in them, and rolled them into short flat cigarettes while he sat on his bike. Everyone liked Josh, Mum thought he was “such a good-looking young man, as bright as a button,” and Dad seemed more happy with him than he had been with the older guys who used to leave almost as soon as they had started. One was fired just because the frost got at Dad’s dahlias.

Unlike the other gardeners, Josh used to let me turn the compost with the long-handled, two-pronged fork that no one else let me touch and empty the mower box onto the heap. He let me weed the front of the borders where we had planted daisy-faced mesembryanthemums that only came out in the sun and balls of alyssum and drifts of pink and white candytuft. I watched the way he tied the clematis up when the string broke once in the wind, and when he used to pee on the compost. “Better not tell your dad I do that, it’s my secret way of getting the compost to work,” he would say, turning as he shook himself and did up his buttons.

My father smiled, beamed almost, when I called plants by their proper names. Antirrhinum instead of snapdragon and Muscari instead of grape hyacinth. He gave a tired but amused little snuffle when I once corrected him about the name of a rose that he had called Pleasure when I knew it was Peace. Josh would take me around the borders, getting me to name as many plants as I could and would tease me when I confused azaleas and rhododendrons. Sometimes he would hoist me up on to his bare shoulders and charge around the garden making airplane noises and pretending to crash into the trees. We played football once, but my saves were so bad that the ball, an orange one belonging to my brothers, kept crashing into the marguerites and knocking them flat. I liked the way Josh would let me sit and talk to him while he took a strip-wash in the outside toilet and changed back into his motorbike leathers. The way he would let me choose a biscuit—a Bourbon, a ginger nut, even a caramel wafer—from his lunchbox and the way he never turned his back on me when he was drying himself with his frayed green-and-white-striped towel.

Jam Tarts

A great deal was made of my being tucked in at night. “I’ll come up and tuck you in” was as near as my mother ever got to playing with me. Tucking me in was her substitute for playing ball, going to the park to play on the slide, being there on sports day, playing hide-and-seek, baking cakes, giving me chocolate kisses, ice cream, toffee apples, making masks, and carving Halloween pumpkins. “I’ll come up and tuck you in” was fine. It’s when she forgot that it wasn’t.

Every few weeks my mother and I would make jam tarts. She had small hands with long, delicate fingers. Gentle, like her name, Kathleen, and that of her siblings, Marjorie and Geoffrey. They say there was some Irish blood somewhere, but like my mother’s asthma no one ever spoke of it.

She would weigh the flour, the butter, the bit of lard that made the pastry so crumbly, and let me rub them all together with my fingertips in the big cream mixing bowl. She poured in cold water from a glass and I brought the dough together into a ball. Her hands started work with the rolling pin, then, once the ball of pastry was flat, I would take over, pushing the pastry out into a great thin sheet. We took the steel cookie cutters, rusty, dusty, and cut out rings of pastry and pushed them into the shallow hollows of an even rustier patty tin.

Mother didn’t like cooking. She did this for me. When she met my father she was working as a secretary to the mayor at the town hall and had never made so much as a sandwich. My father’s first marriage had lasted only a matter of months and was never, ever discussed. (By sheer chance, an old acquaintance of my father’s asked my brother if he was from the first or second marriage. Otherwise we would never have known.) She fell pregnant with me fifteen years after my brother Adrian was born and five years after they adopted his schoolfriend John. That’s when the asthma came on. When she was expecting me.

There had to be three different jams in the tarts. Strawberry, blackcurrant, and lemon curd. It wasn’t till later I learned that plum, damson, and marmalade made the best fillings. I put a couple of spoonfuls of jam into each pastry case, not so much that they would boil over and stick to the tin, but enough that there was more jam than pastry. My father loved a jam tart and would put one in whole and swallow it like a snake devouring a bird’s egg. Despite training as a gunsmith, he now owned a factory where they made parts for Rover cars, a factory that smelled of oil, where the machines were black and stood in pools of oily water. “A man was killed in that one there—he got his overall caught in the roller and it pulled him straight through, flat as a pancake,” my father told me one day as we walked through the black hangar at dusk, its iron roof dripping and the stench of rust around us.

The tarts went in the top oven of the Aga until the edges of the pastry cases turned the pale beige of a Lincoln biscuit and the jam had caramelized around the edges. As the kitchen became hotter and more airless my mother would take her inhaler from the top drawer and take long deep puffs, turning her face away as she did so. Sometimes, she would hold her hand to her chest and close her eyes for a few seconds. A few seconds in which the world seemed to stop.

My mother was polite, quietly spoken, but not timid. I once heard her telling off the delivery boy from Percy Salt’s the grocer because there was something on the bill that shouldn’t have been. I never heard her raise her voice. I am not sure she could have done so if she wanted to. She certainly never did to me.

One day my father came home from work, and even before he had taken off his coat he grabbed one of our jam tarts from the wire cooling rack. He couldn’t have known they had come from the oven only a minute or two before. His hands flapped, his face turned a deep raspberry red, beads of sweat formed like warts on his brow, he danced a merry dance. As he tried to swallow and his eyes filled with the sort of tears a man can only summon when he has boiling lemon curd stuck to the roof of his mouth, I am sure that I saw the faintest of smiles flicker across my mother’s face.

Spaghetti Bolognese

“We . . . are . . . going to have . . . spaghetti, no, SPAGHETTI . . . just try a bit of it. You don’t have to eat it if you DON’T LIKE it.” Mum is yelling into Auntie Fanny’s “good” ear. Quite why she thinks there is a good one and a bad one is a mystery. Everyone knows the old bat is deaf as a post in both.

Neither Fanny nor Mum has eaten spaghetti before, and come to think of it neither have I. Dad is waiting for the water to boil on the Aga. The sauce is already warm, having been poured from its tin a good half-hour ago and is sitting on the cool plate of the Aga, giving just the occasional blip-blop.

When the water finally boils my father shakes the strands of pasta out of the blue sugar paper that looks for all the world like a great long firework, and stands them in the bubbling water. They splay out like one of those fiber-optic lights we saw at the Ideal Home Exhibition on the BBC. As the water comes back to the boil he tries to push the spikes under the water. “They’ll never all go in,” he snaps, trying to read the packet, which, even when read with bifocals, is in Italian. Some of the brittle sticks break in half and clatter over the hot plate.

“Will I like it, Daddy?” I ask, half hoping he’ll change his mind and Mum will cook us all some chops.

“Just try it,” he says, a somewhat exasperated tone creeping in to his voice. “Just try it.” “I think you should put some salt in,” chirps in Mum.

Auntie Fanny is looking down at her lap. “Do I have to have some?” I think she is going to cry.

“I think it must be done now,” says my father twenty minutes later. He drains the slithery lengths of spaghetti in a colander in the sink. Some are escaping through the holes and curling up in the sink like nests of worms. “Quick, get the plates, they’re getting away.” We all sit there staring at our tumbling piles of pasta on our glass Pyrex plates. “Oh, Kathleen, I don’t think I can,” sobs Auntie Fanny, who then picks up a long sticky strand with her fingers and pops it into her mouth from which it hangs all the way down to her lap.

“No, wait for the sauce, Fanny,” Mother sighs, and then quite out of character, “Come on, Daddy, hurry up.” Dad spoons the sauce, a slurry of reddy-brown mince that smells “foreign,” over the knots and twirls of pasta. Suddenly it all seems so grown-up, so sophisticated.

Mum wraps the strands around her fork, “like this, do it like this,” then shovels it toward Fanny’s wet, pink little lips. Most of the pasta falls down Fanny’s skirt, a little of the sauce gets caught on her bottom lip. She licks it off and shudders. “It’s horrible, it’s horrible. He’s trying to poison me,” she wails. We all know she would have said the same even if it had been the most delectable thing she had ever eaten.

Ignoring Fanny’s little tantrum, I do as Mother bids, twirling the pasta around my fork while shoveling the escaping pieces back on with my spoon. I rather like it, the feel of the softly slippery noodles, the rich sauce which is hot, salty, and tastes partly of tomato, partly of Bovril. I wouldn’t mind eating this every day. Unexpectedly, my father takes out a cardboard drum of grated Parmesan cheese and passes it to me to open.

“What’s that you’ve got there?” asks Mum.

“It’s grated cheese, Percy Salt said you have to sprinkle it over the top, it doesn’t work if you don’t.” Now we’re talking. I peel away the piece of paper that is covering the holes and shake the white powder over my sauce. I pass it to my father who does the same. Mum declines as she usually does with anything unusual. There is no point in asking Auntie Fanny, who is by now quietly wetting her pants.

Dad shakes the last of the cheese over his pasta and suddenly everyone goes quiet. I’m looking down but I can see my father out of the corner of my right eye; he has stopped, his fork in midair, a short strand of spaghetti hanging loose. His eyes have gone glassy and he puts his fork back down on his plate.

“Daddy, this cheese smells like sick,” I tell him.

“I know it does, son, don’t eat it. I think it must be off.”

We never had spaghetti bolognese or Parmesan cheese again. Or for that matter, ever even talked about it.

Arctic Roll

There were only three of us at school whose house wasn’t joined to the one next door. Number 67 Sandringham Road, always referred to as “York House,” had mock-Tudor wooden beams, a double garage of which one half doubled as a garden shed and repository for my brothers’ canoes, and a large and crumbling greenhouse. I was also the only one ever to have tasted Arctic Roll. While my friends made do with the pink, white, and brown stripes of a Neapolitan ice cream brick, my father would bring out this newfangled frozen gourmet dessert. Arctic Roll was a sponge-covered tube of vanilla ice cream, its USP being the wrapping of wet sponge and ring of red jam so thin it could have been drawn on with an architect’s pen.

In Wolverhampton, Arctic Roll was considered to be something of a status symbol. It contained mysteries too. Why, for instance, does the ice cream not melt when the sponge defrosts? How is it possible to spread the jam that thin? How come it was made from sponge cake, jam, and ice cream yet managed to taste of cold cardboard? And most importantly, how come cold cardboard tasted so good?

As treats go, this was the big one, bigger even than a Cadbury’s MiniRoll. This wasn’t a holiday or celebration treat like trifle. This was a treat for no obvious occasion. Its appearance had nothing to do with being good, having done well in a school test, having been kind or thoughtful. It was just a treat, served with as much pomp as if it were a roasted swan at a Tudor banquet. I think it was a subtle reminder to the assembled family and friends of how well my father’s business was doing. Whatever, there was no food that received such an ovation in our house. Quite an achievement for something I always thought tasted like a frozen carpet.

Pancakes

Mum never failed to make pancakes on Shrove Tuesday. Light they were, except for the very first one which was always a mess, though for some reason always the best. Mum made thin pancakes, in a battered old frying pan that was black on the outside and smelled of sausages, and we ate them with granulated sugar and Jif lemon. I loved the way the lemon soaked the sugar but never quite dissolved it, so you got the soft pancake, gritty sugar, and sharp lemon all at once.

It was the best day of the year really, especially when she got going and they would come out of the pan as fast as we could eat them. Toward the end Mum would let me flip one. I always contrived it so that it landed on the floor, then she would say, “That’s enough,” and that would be it till next year.

Flapjacks

On crackling winter mornings, with icicles hanging from the drainpipes, Mother would make flapjacks, stirring them in a thick, pitted aluminum pan and leaving them to settle on the back of the Aga. She would use a metal spoon, which acted as an effective alarm clock as it was scraped against the side of the old pan. They were one of the very few treats my mother ever made for us. My father would eat one or two, probably to encourage her rare attempts at homemaking. While I would have to be held back from eating the entire tray. It was their chewy, salty sweetness I loved. Anyone who has never put a really large pinch of salt in with the oats, syrup, and brown sugar is missing a trick. Sometimes, she would leave a flapjack out for Josh too, and we would sit on his motorbike and eat them together. One bitterly cold day, I came home to a hall that smelled of warm biscuits. As I opened the kitchen door I smelled smoke and caught my mother tossing a batch of blackened flapjacks into the bin. There was a bit of charred shrapnel clinging to the edge of the tin which I tried unsuccessfully to prise off. Now they were being tipped into the pedal bin, tray and all. “I’m sorry, darling,” she said, shaking her head. There were tears and something along the lines of “How could you do that, let the flapjacks burn? You’re hopeless, now there won’t be any for Josh tomorrow,” and then I remember stomping into the greenhouse and telling my father he should get a new wife. One who didn’t burn everything.

Percy Salt

If you walked along Penn Road past the fish shop and toward the stately pile that is the Royal School for Boys, you came to Percy Salt’s the grocer’s. It was two shops really, a butcher’s on the right and on the left a cool, tiled grocer’s that had sawdust on the floor and where my mother did most of her shopping. It was here she bought the ham that the young assistants in long white aprons would cut to order from the bone; slices of white- freckled tongue for Dad and tins of peaches and thick Nestlé’s cream for us all. This was where we came for streaky bacon, for sardines, and, at weekends, for cartons of double cream.

Percy Salt’s was the only place where my mother ran a tab. It was the custom for the better-off clientele, as was having their purchases delivered. This was where I would stand while Mum asked to taste the Cheddar or the Caerphilly and where she would pick up round boxes of Dairylea cheeses for me. Sometimes there would be little foil-wrapped triangles of processed cheese flavored with tomato, celery (my favorite), mushroom, and blue cheese. This was also where we came for butter and kippers, salad cream and honey, eggs and tea.

I loved our visits to Salt’s like nothing else. It was the smell of the shop as much as anything, a smell of smoked bacon and truckles of Cheddar, of tomatoes in summer and ham hocks in winter. At Christmas the windows would light up with clementines in colored foil, biscuits in tins with stagecoaches on the lids, fresh pineapples, whole peaches in tins, trifle sponges, and packets of silver balls and sugared almonds. Mother would buy wooden caskets of Turkish delight and crystallized figs, sugared plums, and jars of cherries in brandy. It was here too that she would collect the brandy for the brandy butter, the bottles of Mateus Rosé, the cartons of icing sugar, and the chocolate Christmas decorations that we hung on the tree and that I would sneak one by one over the holidays. Never was I happier than in Percy Salt’s at Christmas, even if my mother did once say he was getting “terribly dear.”

“Dear,” when used in connection with money, was one of the expressions for which my mother would lower her voice, just as she did when she found someone “rather coarse” or when someone had “trodden in something.” “Have you trodden in something” was my mother’s discreet way of asking if you had farted. No surprise then that while Mr. Salt called most of his customers “love” he would always, always call my mother Mrs. Slater.

Sweets, Ices, Rock, and Politics

It would be wrong to say we were wealthy. “Comfortably off” might be nearer the mark, though without the implied smugness. There were tinned peaches and salmon on the shopping list but Mum still checked Percy Salt’s delivery scrupulously, running her finger down the list and ticking things off with a blue biro. Dad took cuttings and planted seeds—yellow snapdragons, nemesia the color of boiled sweets, and those daisy-faced mesembryanthemums that only opened up when the sun shone—because it was cheaper than buying ready-grown bedding plants. Needless to say I had no more pocket money than any of my school friends.

I bought the odd book, annuals mostly, a few singles, “Can’t Buy Me Love” or Dusty Springfield’s “I Only Want to be with You,” and once, a stick insect, but most of my pocket money went on sweets. Buying sweets, chocolate, even ice cream, was shot through with more politics than an eight-year-old should have had to contend with. Sweets could put a label around a child’s neck in much the same way as a particular choice of newspaper could to an adult. For a boy certain things were off-limits. Fry’s Chocolate Creams and Old English Spangles were considered adult territory; Love Hearts and Fab ice creams were for girls. Parma Violets were for old ladies and barley sugars were what your parents bought you for long car journeys. Cones filled with marshmallow and coated in chocolate were considered naff by pretty much everyone, though I secretly liked them, and no one over six would be seen dead with a flying saucer. Sherbet Fountains were supposed to be strictly girly material, an idea which even then I refused to buy into. Milky Ways were what parents bought for their kids, which gave them a sort of goody-goody note as did Jacob’s Orange Clubs. Selection boxes were what you were given at Christmas by the sort of people who weren’t relatives but who nevertheless you called Auntie.

We never really bought the penny chews that Mr. Dixon had loose on the counter, though I did nick the odd licorice chew, the ones that came in blue-and-white-striped paper, when his back was turned. Dad’s favorites were Callard &Bowser’s Butterscotch, which came in thin packs like cigarettes, and Pascall’s oblong Fruit Bonbons with gooey centers. He also loved peanut brittle, which he ate by the barful. Mine were sweet cigarettes, which may not have given me lung cancer but made up for it with fillings. At Christmas, Dad bought himself metal trays of Brazil nut toffee with their own little hammer from Thorntons, while I got more cigarettes, this time made of chocolate wrapped in paper which went soggy when you put it in your mouth. Dad said they were expensive. END

Descriere

'Remarkable' Observer

'Acutely observed, poignant and beautifully written' Daily Telegraph

'My mother is scraping a piece of burned toast out of the kitchen window, a crease of annoyance across her forehead. This is not an occasional occurrence. My mother burns the toast as surely as the sun rises each morning.' Toast is Nigel Slater's award-winning biography of a childhood remembered through food.

Whether recalling his mother's surprisingly good rice pudding, his father's bold foray into spaghetti and his dreaded Boxing Day stew, or such culinary highlights as Arctic Roll and Grilled Grapefruit (then considered something of a status symbol in Wolverhampton), this remarkable memoir vividly recreates daily life in 1960s suburban England. Likes and dislikes, aversions and sweet-toothed weaknesses form a fascinating backdrop to Nigel Slater's incredibly moving and deliciously evocative portrait of childhood, adolescence and sexual awakening.