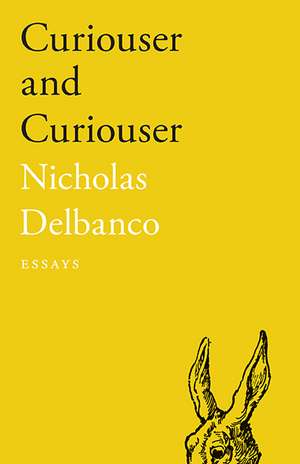

Curiouser and Curiouser: Essays: 21st Century Essays

Autor Nicholas Delbancoen Limba Engleză Paperback – 27 iul 2017

A miscellany of sorts, preeminent author and critic Nicholas Delbanco’s Curiouser and Curiouser attests to a lifelong interest in music and the visual arts as well as both “mere” and “sheer” literature. With essays ranging from the restoration of his father-in-law’s famed Stradivarius cello—known throughout the world as “The Countess of Stanlein”—to a reimagining of H. A. and Margaret Rey’s lives and the creation of their most beloved character, Curious George, Delbanco examines what it means to live and love with the arts.

Whether exploring the history of personal viewing in the business of museum-going, musing on the process of rewriting one’s earliest published work, or looking back on the twists and turns of a life that spans the greater part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Delbanco’s Curiouser and Curiouser invites adventurous readers to follow him down the rabbit hole as he reflects on life as a student, an observer, a writer, a lover, a father, a teacher, and most importantly, a participant in the everyday experiences of human life.

Whether exploring the history of personal viewing in the business of museum-going, musing on the process of rewriting one’s earliest published work, or looking back on the twists and turns of a life that spans the greater part of the twentieth century and into the twenty-first, Delbanco’s Curiouser and Curiouser invites adventurous readers to follow him down the rabbit hole as he reflects on life as a student, an observer, a writer, a lover, a father, a teacher, and most importantly, a participant in the everyday experiences of human life.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 159.59 lei

Preț: 159.59 lei -

Preț: 143.27 lei

Preț: 143.27 lei -

Preț: 107.37 lei

Preț: 107.37 lei -

Preț: 139.50 lei

Preț: 139.50 lei -

Preț: 104.37 lei

Preț: 104.37 lei -

Preț: 111.66 lei

Preț: 111.66 lei -

Preț: 105.41 lei

Preț: 105.41 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 126.49 lei

Preț: 126.49 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 142.93 lei

Preț: 142.93 lei -

Preț: 103.13 lei

Preț: 103.13 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.35 lei

Preț: 145.35 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 169.63 lei

Preț: 169.63 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 141.82 lei

Preț: 141.82 lei -

Preț: 165.55 lei

Preț: 165.55 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 102.95 lei

Preț: 102.95 lei -

Preț: 118.29 lei

Preț: 118.29 lei -

Preț: 149.03 lei

Preț: 149.03 lei

Preț: 110.43 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 166

Preț estimativ în valută:

21.14€ • 21.79$ • 17.82£

21.14€ • 21.79$ • 17.82£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 06-20 februarie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254165

ISBN-10: 0814254160

Pagini: 184

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814254160

Pagini: 184

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 10 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“[Delbanco’s] latest essay collection . . . reveals itself as a musical composition, with repetitions and variations of thematic material weaving in and out of its unfolding.” —Provincetown Arts

“Delbanco has a fine intellect and a sharp pen, and he wields both with precision.” —Harvard Review

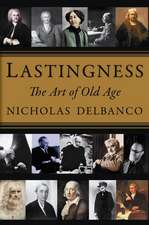

“The Art of Youth is a brilliant book about the power of youth to make great art, itself suffused with youthfulness, with wisdom and diligence and hope. . . .Dazzling in detail and amazingly well informed.” —Paul Theroux, author of Deep South

“Engaging . . . [The Lost Suitcase is] distinguished by its technical virtuosity, self-reflexive perspective, and an improvisational modus operandi.” —Andy Brumer, New York Times Book Review

Notă biografică

Nicholas Delbanco is the author of thirty books of fiction and nonfiction, including the novels The Years, The Count of Concord, and Spring and Fall and his nonfiction works The Art of Youth: Crane, Carrington, Gershwin, and the Nature of First Acts, The Countess of Stanlein Restored, and The Lost Suitcase: Reflections on the Literary Life.

Extras

The Countess of Stanlein Restored

On 22 September 1998, the cellist Bernard Greenhouse drove from his home in Massachusetts the five hours south to Manhattan. On the car’s rear seat reposed his prized possession, named in honor of two of its previous owners: the “Countess of Stanlein ex-Paganini” Stradivarius violoncello of 1707. Strapped down and secure in its carrying case, the instrument traveled wherever he went, and it had done so for years. This afternoon, however, he was planning to realize a long-deferred dream and deposit the “Strad” in New York.

It did require work. There were nicks and scratches scattered on the surface, front and back. The varnish had thickened and darkened in spots; in others the varnish had thinned. Some previous patches needed retouching; in places the edging had cracked. The glue by the sound post—an old repair—leaked. Decades of pressure on the neck and from the downward force of the bridge-feet beneath the taut-stretched strings had warped the f-holes into less than perfect symmetry; the ribs would need to be adjusted and the front plate aligned.

Not all of this was visible, and only the discerning eye would notice or, noticing, object. The instrument had long been famous for both its beauty and tone. But Greenhouse is a perfectionist, and previous repairs had been stopgap and partial, in the service of utility. At the height of his career he performed—with the Bach Aria Group, as a founding member of the Beaux Arts Trio, as soloist and on recordings—more than two hundred times per year. From continent to continent, in all sorts of weather and playing conditions the Countess of Stanlein had been his companion; he carried her on boats and planes, in rented cars and taxicabs and trains, and always in a rush. Now the career was winding down. No longer appearing routinely in concert, he owned several other instruments to practice on at home. At eighty-two, the cellist had the money and unscheduled time and the desire to “give back,” as he put it, “something of value” to the world of music that had given him so much. This was to be, he reasoned, both a good deed and an investment. He knew just the man to do the job—René Morel, on West 54th Street—and the work had been agreed upon and delivery date arranged.

Greenhouse had been a student of the late Pablo Casals. After the Second World War he traveled to Prades, in the French Pyrenees, where the Catalan cellist lived in retirement. As a protest against Generalissimo Franco, Casals accepted no public engagements but continued, in private, to work at his art; there, in the church of San Miguel de Cuxa, he recorded the six Unaccompanied Suites for Violoncello by Johann Sebastian Bach. There too, in 1946, he took on the young American as an apprentice. More than a half century later, that audition stays vivid for Greenhouse:

“He started asking for the repertoire, and he requested many pieces. After an hour or more of my playing—during which he indicated nothing more than the piece and the passage he wanted me to play—he said, ‘All right. Put down your cello, put it away, and we’ll talk.’ He said to me, ‘Well, what you need is an apprenticeship to a great artist. I believe in the apprentice system. Stradivari, Guarneri, Amati: they turned out so many wonderful violin makers. And I believe the same thing can hold true in making musicians. If I knew of a great artist I could send you to, I would do so,’ he said, ‘because my mind is very much occupied with the Spanish Republican cause. But since I don’t know whom to send you to—and if you agree to stay in the village and take a lesson at least once every two days—I will teach you.’”

Such a system of tutelage remains in place today: implicit in the idea of “master classes” and explicit in the trade of the luthier. This is a generic term for those who make and repair bowed stringed instruments, and the enterprise feels nearly medieval in its hierarchy of apprentice, journeyman laborer, master craftsman. Young men still clean the varnish rags or sweep wood shavings from the floor as did their predecessors centuries ago, and under much the same close watchful supervision. Bernard Greenhouse met René Morel in the early 1950s when the luthier was working for the legendary Fernando Sacconi in the New York shop of Rembert Wurlitzer; he commended the Frenchman thereafter to the dealer Jacques Français. In 1994 Morel struck out on his own, as both dealer and restorer. His long and narrow workroom is chock-a-block with wood and tools and objects in molds and on benches; his public rooms display memorabilia—signed concert posters and photographs of virtuosi—from the storied past.

On 22 September 1998, the cellist Bernard Greenhouse drove from his home in Massachusetts the five hours south to Manhattan. On the car’s rear seat reposed his prized possession, named in honor of two of its previous owners: the “Countess of Stanlein ex-Paganini” Stradivarius violoncello of 1707. Strapped down and secure in its carrying case, the instrument traveled wherever he went, and it had done so for years. This afternoon, however, he was planning to realize a long-deferred dream and deposit the “Strad” in New York.

It did require work. There were nicks and scratches scattered on the surface, front and back. The varnish had thickened and darkened in spots; in others the varnish had thinned. Some previous patches needed retouching; in places the edging had cracked. The glue by the sound post—an old repair—leaked. Decades of pressure on the neck and from the downward force of the bridge-feet beneath the taut-stretched strings had warped the f-holes into less than perfect symmetry; the ribs would need to be adjusted and the front plate aligned.

Not all of this was visible, and only the discerning eye would notice or, noticing, object. The instrument had long been famous for both its beauty and tone. But Greenhouse is a perfectionist, and previous repairs had been stopgap and partial, in the service of utility. At the height of his career he performed—with the Bach Aria Group, as a founding member of the Beaux Arts Trio, as soloist and on recordings—more than two hundred times per year. From continent to continent, in all sorts of weather and playing conditions the Countess of Stanlein had been his companion; he carried her on boats and planes, in rented cars and taxicabs and trains, and always in a rush. Now the career was winding down. No longer appearing routinely in concert, he owned several other instruments to practice on at home. At eighty-two, the cellist had the money and unscheduled time and the desire to “give back,” as he put it, “something of value” to the world of music that had given him so much. This was to be, he reasoned, both a good deed and an investment. He knew just the man to do the job—René Morel, on West 54th Street—and the work had been agreed upon and delivery date arranged.

Greenhouse had been a student of the late Pablo Casals. After the Second World War he traveled to Prades, in the French Pyrenees, where the Catalan cellist lived in retirement. As a protest against Generalissimo Franco, Casals accepted no public engagements but continued, in private, to work at his art; there, in the church of San Miguel de Cuxa, he recorded the six Unaccompanied Suites for Violoncello by Johann Sebastian Bach. There too, in 1946, he took on the young American as an apprentice. More than a half century later, that audition stays vivid for Greenhouse:

“He started asking for the repertoire, and he requested many pieces. After an hour or more of my playing—during which he indicated nothing more than the piece and the passage he wanted me to play—he said, ‘All right. Put down your cello, put it away, and we’ll talk.’ He said to me, ‘Well, what you need is an apprenticeship to a great artist. I believe in the apprentice system. Stradivari, Guarneri, Amati: they turned out so many wonderful violin makers. And I believe the same thing can hold true in making musicians. If I knew of a great artist I could send you to, I would do so,’ he said, ‘because my mind is very much occupied with the Spanish Republican cause. But since I don’t know whom to send you to—and if you agree to stay in the village and take a lesson at least once every two days—I will teach you.’”

Such a system of tutelage remains in place today: implicit in the idea of “master classes” and explicit in the trade of the luthier. This is a generic term for those who make and repair bowed stringed instruments, and the enterprise feels nearly medieval in its hierarchy of apprentice, journeyman laborer, master craftsman. Young men still clean the varnish rags or sweep wood shavings from the floor as did their predecessors centuries ago, and under much the same close watchful supervision. Bernard Greenhouse met René Morel in the early 1950s when the luthier was working for the legendary Fernando Sacconi in the New York shop of Rembert Wurlitzer; he commended the Frenchman thereafter to the dealer Jacques Français. In 1994 Morel struck out on his own, as both dealer and restorer. His long and narrow workroom is chock-a-block with wood and tools and objects in molds and on benches; his public rooms display memorabilia—signed concert posters and photographs of virtuosi—from the storied past.