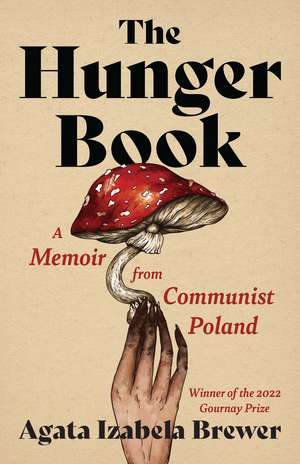

The Hunger Book: A Memoir from Communist Poland: 21st Century Essays

Autor Agata Izabela Breweren Limba Engleză Paperback – 29 sep 2023

In The Hunger Book, Agata Izabela Brewer evokes her Polish childhood under Communism, where the warmth of her grandparents’ love and the scent of mushrooms drying in a tiny apartment are as potent as the deprivations and traumas of life with a terrifyingly unstable, alcoholic single mother. Brewer indelibly renders stories of foraging for food, homemade potato vodka (one of the Eastern Bloc’s more viable currencies), blood sausage, sparrows plucked and fried with linseed oil, and the respite of a country garden plot, all amid Stalinist-era apartment buildings, food shortages, martial law, and nuclear disaster in nearby Ukraine.

Brewer reflects on all of this from her immigrant’s vantage point, as she wryly tries to convince her children to enjoy the mushrooms she gathers from a roadside and grieves when they choose to go by Americanized versions of their Polish names. Hunting mushrooms, like her childhood, carried both reward and mortal peril. The Hunger Book, which includes recipes, is an unforgettable meditation on motherhood and addiction, resilience and love.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 211

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.88€ • 28.06$ • 22.25£

26.88€ • 28.06$ • 22.25£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814258781

ISBN-10: 0814258786

Pagini: 254

Ilustrații: 6 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814258786

Pagini: 254

Ilustrații: 6 b&w images

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.31 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“A searing memoir about growing up behind the Iron Curtain, motherhood, addiction, and finding sustenance in the natural world.…A memorable meditation on hunger for food and love, childhood in a totalitarian regime, and resilience.” —Kirkus

“The Hunger Book is a forthright, tender memoir about intergenerational trauma and the nuances of maternal love.” —Michelle Anne Schingler, Foreword Reviews

“Deeply moving . . . the book evokes viscerally remembered historical moments . . . If memoir writing is about making meaning out of memories, and good nonfiction is about living in someone else’s head for the spell of a narrative, you will be glad you spent time in the thoughtful, insightful mind of Agata Izabela Brewer, digging for meaning.” —Ania Spyra, Chicago Review of Books

“The Hunger Book is vivid, startling, and lush with the smells of wild mushrooms and rose petal jam. This captivating family story reminds us that we hunger for more than food.” —Dinty W. Moore, author of Between Panic & Desire

“What a rare and harrowing pleasure! Agata Izabela Brewer spins a bleak, tender, gorgeously riveting tale from material both sweepingly political and mesmerizingly intimate. The miracle—and our great good fortune—is that she survived, that she is here to tell it.” —Joy Castro, author of One Brilliant Flame

“A fascinating story of one woman’s divided loyalties, an ode and a lament told in brisk and unusual prose. Brewer does a gorgeous job of tying together the toxic and beneficial sides of mushrooms, mothers, and motherlands. A page-turner from which I learned a great deal.” —Jennifer Croft, Booker Prize–winning translator of Olga Tokarczuk’s work

“The Hunger Book is a forthright, tender memoir about intergenerational trauma and the nuances of maternal love.” —Michelle Anne Schingler, Foreword Reviews

“Deeply moving . . . the book evokes viscerally remembered historical moments . . . If memoir writing is about making meaning out of memories, and good nonfiction is about living in someone else’s head for the spell of a narrative, you will be glad you spent time in the thoughtful, insightful mind of Agata Izabela Brewer, digging for meaning.” —Ania Spyra, Chicago Review of Books

“The Hunger Book is vivid, startling, and lush with the smells of wild mushrooms and rose petal jam. This captivating family story reminds us that we hunger for more than food.” —Dinty W. Moore, author of Between Panic & Desire

“What a rare and harrowing pleasure! Agata Izabela Brewer spins a bleak, tender, gorgeously riveting tale from material both sweepingly political and mesmerizingly intimate. The miracle—and our great good fortune—is that she survived, that she is here to tell it.” —Joy Castro, author of One Brilliant Flame

“A fascinating story of one woman’s divided loyalties, an ode and a lament told in brisk and unusual prose. Brewer does a gorgeous job of tying together the toxic and beneficial sides of mushrooms, mothers, and motherlands. A page-turner from which I learned a great deal.” —Jennifer Croft, Booker Prize–winning translator of Olga Tokarczuk’s work

Notă biografică

Agata Izabela Brewer was born and raised in Poland. A teacher, a mother, an activist for immigrant rights, and a Court Appointed Special Advocate, she is Professor of English at Wabash College. Her creative writing has appeared in Guernica and Entropy. The Hunger Book is her first book of creative nonfiction.

Extras

Mother, who taught high school English until her self-destructive behavior made it impossible to show up in class sober, sang Mother Goose nursery rhymes to me as she sat at the kitchen table sipping on her vodka. After an hour or two of drinking, she'd switch to singing Polish revolutionary songs about starving peasants. "Sing a Song of Sixpence" was in her repertoire. Although some say that this rhyme is really about King Henry VIII's break from the Catholic Church, with the birds representing the church, and the maid who appears later in the song representing Ann Boleyn, the dish with live birds really existed. On occasion, cooks would replace birds with frogs, rabbits, or even poetry-reciting dwarfs. Nowadays some bakers use so-called pie birds-hollow ceramic figures of birds placed in the middle of their pie-to provide ventilation and prevent the contents of the pie spilling over as the heat rises.

What was once an elaborate, fancy meal on the tables of nobles in Genoa and Paris and a source of entertainment between dishes became a base form of sustenance in lean postwar Poland, especially in the countryside. Teresa's family bent over the sparrows' boiled flesh sprinkled with salt and with deft fingers picked around the keel-like sternum, the furcula, the humerus, radius, and ulna, stripping the birds of the now-beige meat.

These must have been Eurasian tree sparrows, which, despite their name, often build nests on buildings, like their slightly larger urban cousins, house sparrows. Their chestnut-colored crowns and white cheeks with a contrasting black pattern bob up and down as they search for seeds and worms. With a clutch of about six eggs, they breed fast and used to be plentiful in the Polish countryside, especially before the widespread use of herbicides that now contribute to their declining population. Their high-pitched chirps and cheeps carry a long way from the roof cavities of empty buildings or from pollarded willows. They sometimes breed in nests abandoned by magpies and storks. Their own untidy nests are made of sticks, grass, hay, and wool and are insulated with feathers.

Both parents incubate their small, blotchy eggs. Sparrows are an altricial species, which means that their young are incapable of taking care of themselves. As they emerge from the eggs, young sparrows need to be nurtured and protected as they fledge and before they take flight. The parents guard the little ones against owls and hawks. Some nests are attacked by weasels and rats. In postwar Poland, they were also raided by hungry humans.

Hungry Poles were their predators, but so was Mao Zedong, who ordered 3 million Chinese peasants to eradicate sparrows in the Four Pests Campaign of 1958 to reduce grain crop damage. Sparrows were declared the enemy of Communism. Like bloodsucking capitalists, sparrows stole the products of people's labor, filling their plump bellies without hard work. During the campaign, they mostly died of exhaustion, as the favored weapons against them were pots, pans, and spoons. Sparrows cannot stay in the air for long. They need to perch and rest often. When they cannot do that, their little hearts fail. Humans made so much noise with their cooking utensils in the countryside that sparrows couldn't land in their nests or on trees and eventually dropped dead to the ground. They were also attacked in cities, including Beijing, where the military as well as volunteering schoolchildren killed them en masse. Ironically, some sparrows escaped to the grounds of the Polish embassy in Beijing, which proved a sanctuary for them because the diplomats there refused to let the Chinese enter and kill the birds. In the end, the embassy was surrounded by people with pots and pans, and a few days later, the embassy staff had to shovel out thousands of dead sparrows. As with other campaigns designed to meddle with the environment on a massive scale, this one backfired. The sparrow population diminished in China, and the number of locusts and other insects increased, which contributed to the 1959-61 famine during which 30 million people died. By then, there were almost no sparrows left to eat.

What was once an elaborate, fancy meal on the tables of nobles in Genoa and Paris and a source of entertainment between dishes became a base form of sustenance in lean postwar Poland, especially in the countryside. Teresa's family bent over the sparrows' boiled flesh sprinkled with salt and with deft fingers picked around the keel-like sternum, the furcula, the humerus, radius, and ulna, stripping the birds of the now-beige meat.

These must have been Eurasian tree sparrows, which, despite their name, often build nests on buildings, like their slightly larger urban cousins, house sparrows. Their chestnut-colored crowns and white cheeks with a contrasting black pattern bob up and down as they search for seeds and worms. With a clutch of about six eggs, they breed fast and used to be plentiful in the Polish countryside, especially before the widespread use of herbicides that now contribute to their declining population. Their high-pitched chirps and cheeps carry a long way from the roof cavities of empty buildings or from pollarded willows. They sometimes breed in nests abandoned by magpies and storks. Their own untidy nests are made of sticks, grass, hay, and wool and are insulated with feathers.

Both parents incubate their small, blotchy eggs. Sparrows are an altricial species, which means that their young are incapable of taking care of themselves. As they emerge from the eggs, young sparrows need to be nurtured and protected as they fledge and before they take flight. The parents guard the little ones against owls and hawks. Some nests are attacked by weasels and rats. In postwar Poland, they were also raided by hungry humans.

Hungry Poles were their predators, but so was Mao Zedong, who ordered 3 million Chinese peasants to eradicate sparrows in the Four Pests Campaign of 1958 to reduce grain crop damage. Sparrows were declared the enemy of Communism. Like bloodsucking capitalists, sparrows stole the products of people's labor, filling their plump bellies without hard work. During the campaign, they mostly died of exhaustion, as the favored weapons against them were pots, pans, and spoons. Sparrows cannot stay in the air for long. They need to perch and rest often. When they cannot do that, their little hearts fail. Humans made so much noise with their cooking utensils in the countryside that sparrows couldn't land in their nests or on trees and eventually dropped dead to the ground. They were also attacked in cities, including Beijing, where the military as well as volunteering schoolchildren killed them en masse. Ironically, some sparrows escaped to the grounds of the Polish embassy in Beijing, which proved a sanctuary for them because the diplomats there refused to let the Chinese enter and kill the birds. In the end, the embassy was surrounded by people with pots and pans, and a few days later, the embassy staff had to shovel out thousands of dead sparrows. As with other campaigns designed to meddle with the environment on a massive scale, this one backfired. The sparrow population diminished in China, and the number of locusts and other insects increased, which contributed to the 1959-61 famine during which 30 million people died. By then, there were almost no sparrows left to eat.

Cuprins

Mushrooms

Birds

Roots

Lard

Bread

Blood

Carp

Vodka

Mushrooms II

Hunger

Birds

Roots

Lard

Bread

Blood

Carp

Vodka

Mushrooms II

Hunger

Descriere

Essays, with recipes, about food, deprivation, and resilience during a childhood under the last years of Poland’s Communist regime as the daughter of an unstable, alcoholic mother.