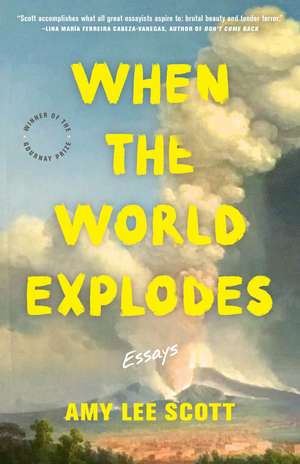

When the World Explodes: Essays: 21st Century Essays

Autor Amy Lee Scotten Limba Engleză Paperback – 6 mar 2025

How do you survive when your world explodes? By the time she was seven, Amy Lee Scott had seen her world end twice: first as an infant, when adoption brought her from Korea to Ohio, and again when her adoptive mother died of cancer. Orphaned twice over, Scott confronts her personal chaos by investigating a litany of historic catastrophes and the disruptions that followed. Witnessing a Cabbage Patch Kid “born” at BabyLand General Hospital inspires a meditation on the history of Korean adoption and her own origins. Recalling her miscarriage as the streets of her Detroit neighborhood flooded, she asks what it means to mourn what would have been. And she remembers her mother’s illness and death amid the 1992 Los Angeles riots. In this haunting debut, Scott gets to the heart of what it means to wrestle with the grief, rage, and anxiety seething in this tender world. Ferocious and true, When the World Explodes probes the space between personal and global calamities—from Krakatoa to the emotional perils of motherhood—to unearth the sharp ridge of hope that hides beneath the rubble.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 157

Preț estimativ în valută:

20.08€ • 20.97$ • 16.62£

20.08€ • 20.97$ • 16.62£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814259177

ISBN-10: 0814259170

Pagini: 192

Ilustrații: 17 black and white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814259170

Pagini: 192

Ilustrații: 17 black and white illustrations

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 23 mm

Greutate: 0.23 kg

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“When the World Explodes is a collection both explosive and tender, epic in its scope yet granular in its concerns. Writing with the precision and wonder of a poet, Amy Lee Scott reaches back in time, excavating science and history alongside her own lost story of origin, to reveal an understanding of the present that feels fierce, loving, and new.” —Sarah Viren, author of To Name the Bigger Lie and Mine

“Spare and unsparing, When the World Explodes quakes with anxiety, simmers with rage, and breaks open with loss after loss. Amy Lee Scott manages to take refuge in research, collecting the fragments of cataclysm and reverberation, while surveying a shifting landscape of tragedy, transformation, and escape. This book knows how to keep its distance, to keep at arm’s length forces that bring us to our knees—yet it takes us again and again to the brink.” —A. Kendra Green, author of No Less Strange or Wonderful: Essays in Curiosity

“More of a dare to live than a meditation on life, When the World Explodes gathers up stories as if it would starve without them. Unblinking and entreating the reader not to blink, it posits that the risk of loss pales in comparison to the risk of a life where nothing was risked. In this book, Scott accomplishes what all great essayists aspire to: brutal beauty and tender terror.” —Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas, author of Don’t Come Back

“When the World Explodes speaks to the vast, haunting layers of transracial adoptee grief. These essays sing forth with lyrical and sensory depth, braided with questions of belonging and selfhood, and tie personal grief—the loss of both of Scott’s mothers—to the trembling world around us. This collection will open your heart.” —Jane Wong, author of How Not to Be Afraid of Everything

“Amy Lee Scott bravely mines the depths of her own grief and emerges with moments of heartbreaking clarity. Blending these personal reflections with explorations of larger-scale cultural traumas, her essays are deeply introspective but never navel-gazing, full of fear and hope and love. A jewel box of grief.” —Tyler Feder, author of Dancing at the Pity Party

"This richly written book is both vulnerable and unflinching; it does not flinch from conflagrations, it does not flinch from joy. Honoring the enormity of disasters as well as the delicacy of flying spiders—and babies—who start life up again after a disaster, Scott’s book thawed my heart, and I felt the miracle of our delicate flying lives." —Amy Leach, author of The Everybody Ensemble

Notă biografică

Amy Lee Scott received an MFA from the University of Iowa Nonfiction Writing Program. Her writing can be found in Tin House Online,Gettysburg Review,Gulf Coast,New Letters,Fourth Genre,Southern Review,Michigan Quarterly Review, and elsewhere.

Extras

I was pregnant before you, once. I could only eat pizza. None of the glorious lomos saltados your father devoured while we hiked around Peru. The air was thin there. I slept a lot. We didn’t know.

When I got home, I took five pregnancy tests because I couldn’t believe the first one. I lined all the plastic sticks up on the bathtub rim and tried to feel anything. I tried to imagine a baby but all I could see were pails of dirty diapers, infinite loads of laundry. I could hear a baby squalling somewhere.

What I haven’t told you is that I never wanted to be a mother.

It was a surprise then, my grief, when the ultrasound turned up empty. What should have been a fig-sized something was a nothing. The doctor called it a blighted ovum, where the placenta develops without an embryo inside.

Apparently, the placenta grew for eight weeks and then stopped. But I kept feeling pregnant even as weeks 7, 8, 9, 10, then 11 chugged by. The empty sac kept telling my body to feel pregnant when all along it was just treading water.

After the news I wondered if it had happened because of my ambivalence. Like somehow the phantom fig knew it wasn’t wanted, at least theoretically. It was only its absence that made me see and miss the child I would never hold.

I obsessed over it: at six weeks 6, Baby is supposed to be the size of a lentil; at eleven weeks 11, the size of a fig. Instead, I had my insides scraped clean. For months afterwards, I cried at inopportune times. I could not stop mourning the loss of my nothing.

When I was a little girl my best friend’s grandmother died. She and her family sat shiva and ate lentils. She didn’t know why. Her mom explained that their round shape symbolized “the circle of life” and she couldn’t help it, my friend giggled, because what did Rafiki thrusting baby Simba into the African sunrise have to do with her dead grandmother?

Hamakom y’nachem etkhem b’tokh sha’ar avelei tzioyon viyrushalayin.

*

I was born with another name in another country to another family. Someone—not my Korean mother—named me Yung Hwa, eternal blossom. It wasn’t until much later, after I had you in fact, that I looked up Korea’s national flower, a hibiscus of many names.

We in America know it as the Rose of Sharon. In Britain it is known as “rose mallow” while in Italy it is St. Joseph’s rod.

In Korea it is called mugunghwa, meaning “eternal blossom that never fades.”

I saw it when we honeymooned in Korea but didn’t have a name for it then. Looking back through photos I see it everywhere: framing homes and government buildings, temples, and UNESCO sites. I can almost smell the perfume wafting from the pink flowers blooming by my orphanage that we somehow found and visited.

The director didn’t speak much English, but she’d been there from the start, when she cared for wWar orphans a lifetime ago. Of course, she didn’t remember me but she beamed and beamed. She looked at me hungrily, like she couldn’t get enough, and kept squeezing my hand. “You are so healthy,” she kept saying, “so, so healthy.”

I thought about how many babies must have passed through this woman’s arms. I wondered how it felt to care for so many babies only to let them all go. She must have felt a weight lifting and descending all at once when a baby left her arms for the final time, just the same as me when they placed you on my chest for the first time, naked and squalling.

When I got home, I took five pregnancy tests because I couldn’t believe the first one. I lined all the plastic sticks up on the bathtub rim and tried to feel anything. I tried to imagine a baby but all I could see were pails of dirty diapers, infinite loads of laundry. I could hear a baby squalling somewhere.

What I haven’t told you is that I never wanted to be a mother.

It was a surprise then, my grief, when the ultrasound turned up empty. What should have been a fig-sized something was a nothing. The doctor called it a blighted ovum, where the placenta develops without an embryo inside.

Apparently, the placenta grew for eight weeks and then stopped. But I kept feeling pregnant even as weeks 7, 8, 9, 10, then 11 chugged by. The empty sac kept telling my body to feel pregnant when all along it was just treading water.

After the news I wondered if it had happened because of my ambivalence. Like somehow the phantom fig knew it wasn’t wanted, at least theoretically. It was only its absence that made me see and miss the child I would never hold.

I obsessed over it: at six weeks 6, Baby is supposed to be the size of a lentil; at eleven weeks 11, the size of a fig. Instead, I had my insides scraped clean. For months afterwards, I cried at inopportune times. I could not stop mourning the loss of my nothing.

When I was a little girl my best friend’s grandmother died. She and her family sat shiva and ate lentils. She didn’t know why. Her mom explained that their round shape symbolized “the circle of life” and she couldn’t help it, my friend giggled, because what did Rafiki thrusting baby Simba into the African sunrise have to do with her dead grandmother?

Hamakom y’nachem etkhem b’tokh sha’ar avelei tzioyon viyrushalayin.

*

I was born with another name in another country to another family. Someone—not my Korean mother—named me Yung Hwa, eternal blossom. It wasn’t until much later, after I had you in fact, that I looked up Korea’s national flower, a hibiscus of many names.

We in America know it as the Rose of Sharon. In Britain it is known as “rose mallow” while in Italy it is St. Joseph’s rod.

In Korea it is called mugunghwa, meaning “eternal blossom that never fades.”

I saw it when we honeymooned in Korea but didn’t have a name for it then. Looking back through photos I see it everywhere: framing homes and government buildings, temples, and UNESCO sites. I can almost smell the perfume wafting from the pink flowers blooming by my orphanage that we somehow found and visited.

The director didn’t speak much English, but she’d been there from the start, when she cared for wWar orphans a lifetime ago. Of course, she didn’t remember me but she beamed and beamed. She looked at me hungrily, like she couldn’t get enough, and kept squeezing my hand. “You are so healthy,” she kept saying, “so, so healthy.”

I thought about how many babies must have passed through this woman’s arms. I wondered how it felt to care for so many babies only to let them all go. She must have felt a weight lifting and descending all at once when a baby left her arms for the final time, just the same as me when they placed you on my chest for the first time, naked and squalling.

Cuprins

When the World Explodes Conflagrations, and the Quelling Of Convergence BabyLand Of Floods and Ruination Field Guide to a Common Pregnancy: Notes on Loss and Growth Theories of Cosmogony Everyone Knows One How Do You Name a Hurricane? How to Survive an Active Attacker Airborne Toxic Events Acknowledgments Selected Sources

Descriere

Excavates both personal and public calamities to explore parental loss, motherhood, and transracial adoptee experience.