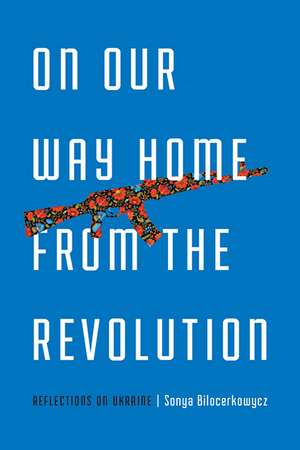

On Our Way Home from the Revolution: Reflections on Ukraine: 21st Century Essays

Autor Sonya Bilocerkowyczen Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 sep 2019 – vârsta ani

In 2014 Sonya Bilocerkowycz is a tourist at a deadly revolution. At first she is enamored with the Ukrainians’ idealism, which reminds her of her own patriotic family. But when the romantic revolution melts into a war with Russia, she becomes disillusioned, prompting a return home to the US and the diaspora community that raised her. As the daughter of a man who studies Ukrainian dissidents for a living, the granddaughter of war refugees, and the great-granddaughter of a gulag victim, Bilocerkowycz has inherited a legacy of political oppression. But what does it mean when she discovers a missing page from her family’s survival story—one that raises questions about her own guilt? In these linked essays, Bilocerkowycz invites readers to meet a swirling cast of post-Soviet characters, including a Russian intelligence officer who finds Osama bin Laden a few weeks after 9/11; a Ukrainian poet whose nose gets broken by Russian separatists; and a long-lost relative who drives a bus into the heart of Chernobyl. On Our Way Home from the Revolution muddles our easy distinctions between innocence and culpability, agency and fate.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.06 lei

Preț: 166.06 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 170.25 lei

Preț: 170.25 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 145.35 lei

Preț: 145.35 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.50 lei

Preț: 173.50 lei -

Preț: 172.69 lei

Preț: 172.69 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 223

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.46€ • 30.92$ • 23.92£

28.46€ • 30.92$ • 23.92£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 17-23 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814255438

ISBN-10: 0814255434

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814255434

Pagini: 232

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 36 mm

Greutate: 0.3 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

"The granddaughter of Ukrainian refugees growing up in Ukrainian diasporic communities, Bilocerkowycz inherited a legacy of political oppression. In these linked essays, the Ukrainian American writer unpacks that legacy and the evolution of her patriotism and national identity growing up in the U.S." —Barbara VanDenburgh, USA Today

“An emotionally urgent personal reckoning … The granddaughter of Ukrainian refugees, [Bilocerkowycz] grew up steeped in the myths, the language, and the fierce politics of her Ukrainian-American community. On Our Way Home from the Revolution … opens on the moment when some of these myths and political convictions begin to fray. The subsequent book-length unraveling becomes an affecting meditation on how our identities are formed, and to whom we are responsible.” —John Dixon Mirisola, Los Angeles Review of Books

"Through these intimate reflections, Bilocerkowicz interweaves post-Soviet narratives and family mythology, creating a tapestry of interconnected essays that illuminate the complexity and responsibility of being a child of the Ukrainian diaspora. A tender and fearless read." —Kalani Pickhart, Electric Literature

“The essays build to a shocking discovery that provides a thud of misunderstanding about our collective pasts—our very ideas of ourselves—that is so profound that I have a hard time imagining a reader who will not feel equally stunned and seen.…[A] magnificent debut.”—Annie McGreevy,Chicago Review of Books

“A fierce, lyrical book that achieves a rare balance between the burden and beauty of heritage. A powerfully American book even as it travels to post–Cold War Ukraine. The best use of memoir is not a how-I-got-to-be-me story, but a book like this—a courageous effort to pierce the secrets of a vexed political and cultural history.” —Patricia Hampl

“Part mythology, part personal essay, and part historical fact-finding mission that circles her family’s patriotic devotion to Ukraine, Sonya Bilocerkowycz asks what it means to love a country that struggles to confront its complicated history and wonders what to make of the incomplete narrative she inherited as a child. Tender, probing, and deeply honest.” —Angela Pelster

Notă biografică

Sonya Bilocerkowycz’s work has appeared in Guernica, Colorado Review, The Southampton Review, Image, Ninth Letter, and Crab Orchard Review. She has served as a Fulbright grantee in Belarus, an educational recruiter in the Republic of Georgia, and an instructor at Ukrainian Catholic University. She is a 2022 National Endowment for the Arts Creative Writing Fellow.

Extras

Excerpt from the essay "Bloodlines (Or, Although a Good Man, a Muscovite)"

When I graduated from high school, my father took me on a long-awaited, much-anticipated trip to Ukraine. He and I would visit our relatives Marina and Yarosh in the village, but mostly we would just be tourists, stay in Western hotels in the major cities, eat at the best restaurants, sightsee, souvenir shop, inject dollars into the local economy and understand that we are being useful to someone. Diaspora families are always doing this.

My father bought for us what was, in 2007, the only English-language guidebook available for Ukraine. It was published by Lonely Planet, and the cover photo was of a castle, situated over a craggy cliff that dropped into what appeared to be a vast ocean. The castle had gothic windows, spires with flags, and princess balconies, all the whimsical features one associates with Disney, and the scene was filtered orange by a low sun. It looked majestic, but I didn’t know then that the castle is actually a miniature, roughly the square footage of a small house. In the cover photo, there was no way to measure for scale.

I remember studying the picture and information inside—“The Swallow’s Nest is one of several châteaux fantastiques located near Yalta on the Crimean peninsula”—and comprehending, perhaps for the very first time, that Ukraine had an entire border made of water. Chorne More, the Black Sea. Palaces and oceans must not have been part of my grandmother’s Ukraine, or surely I would have heard about them. All I ever heard about were the pigs, the potatoes, the purling river Ikva. I was taken by the orange Swallow’s Nest, but the idea of this bigger thing—the Black Sea—piqued my interest primarily because of how it might supplement our vacation: I was a teenage girl who wanted to lie on the beach and come home with a tan.

Tato, why don’t we go to Crimea? I asked my father.

We don’t want to go there, he said. It’s heavily Russified.

So what?

Just trust me, he waved his hand, the way people do when swatting a fly.

I dropped the issue without a fight and didn’t think about that conversation again until a few years later, around the time when this awareness started to emerge that our family was more afraid of something than other families—at least, it seemed, more afraid than the mostly white middle-class families that formed the periphery of my childhood. Or perhaps our family’s fear was more specific. It was fear manifested as quiet contempt.

On that first trip in 2007, I bought a t-shirt from the souvenir vendors in Lviv’s Vernisage Market. I slept in it every night for a month because it was so soft. I saw nothing wrong with the shirt, and neither, apparently, did my father. In large purple letters it read:

Дякую тобі боже що я не Москаль.

Thanks be to God that I’m not a Moskal.

+++

My attempts to assign more complex vocabulary to this phenomenon have not felt entirely fruitful. This isn’t xenophobia, because after decades of occupation, oppression, murder, surveillance, a state-engineered famine, and the current ongoing invasion, my family’s distaste for Russia isn’t exactly irrational, as the definition suggests it should be. In Greek xenos refers to the strange, foreign, or unfamiliar, and that part isn’t so cut-and-dry either. Though western Ukrainians especially tend to “otherize” Russians, it is also true that by most visible markers—culture, religion, physical attributes, lifestyle—the groups aren’t so different at all. Both Busia and my father speak Russian in addition to Ukrainian. This is not a straightforward case of hating the unfamiliar.

Maybe bigotry is closer, but that term places special emphasis on opinions and ideas. Is it bigoted to dislike those who march through the world with imperial aims? Those who seem incapable of treating you without condescension?

Instead, it might best be characterized as enmity—“a very deep unfriendly feeling.” The word enmity conjures up a hostility of biblical proportions: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, between your offspring and hers.” In this analogy, the Russians are, of course, the dust-eating serpent. Enmity is a literary word, one that implies hatred left over from some long-ago circumstance. There is also an element of passivity. It has been this way since before we were born. It has always been like this. This is part of us.

Taras Shevchenko, the 19th-century poet who wrote Kateryna, meant the poem as an allegory. Soldier Ivan represents the Russian Empire, while Kateryna is the feminized, virginal, and subjugated Ukrainian nation. Shevchenko himself was born an imperial serf and didn’t have his freedom purchased until age 24, when, interestingly, a Russian poet was able to use his influence in Shevchenko’s favor. Luckily, Shevchenko was a talented artist.

Today Shevchenko is considered the father of modern Ukrainian literature and a useful national symbol. He remains highly venerated in Ukraine and his face appears on the 100 hryven bill. Busia and my father both have embroidered portraits of the mustachioed poet in their living rooms. Many Ukrainians do.

When I graduated from high school, my father took me on a long-awaited, much-anticipated trip to Ukraine. He and I would visit our relatives Marina and Yarosh in the village, but mostly we would just be tourists, stay in Western hotels in the major cities, eat at the best restaurants, sightsee, souvenir shop, inject dollars into the local economy and understand that we are being useful to someone. Diaspora families are always doing this.

My father bought for us what was, in 2007, the only English-language guidebook available for Ukraine. It was published by Lonely Planet, and the cover photo was of a castle, situated over a craggy cliff that dropped into what appeared to be a vast ocean. The castle had gothic windows, spires with flags, and princess balconies, all the whimsical features one associates with Disney, and the scene was filtered orange by a low sun. It looked majestic, but I didn’t know then that the castle is actually a miniature, roughly the square footage of a small house. In the cover photo, there was no way to measure for scale.

I remember studying the picture and information inside—“The Swallow’s Nest is one of several châteaux fantastiques located near Yalta on the Crimean peninsula”—and comprehending, perhaps for the very first time, that Ukraine had an entire border made of water. Chorne More, the Black Sea. Palaces and oceans must not have been part of my grandmother’s Ukraine, or surely I would have heard about them. All I ever heard about were the pigs, the potatoes, the purling river Ikva. I was taken by the orange Swallow’s Nest, but the idea of this bigger thing—the Black Sea—piqued my interest primarily because of how it might supplement our vacation: I was a teenage girl who wanted to lie on the beach and come home with a tan.

Tato, why don’t we go to Crimea? I asked my father.

We don’t want to go there, he said. It’s heavily Russified.

So what?

Just trust me, he waved his hand, the way people do when swatting a fly.

I dropped the issue without a fight and didn’t think about that conversation again until a few years later, around the time when this awareness started to emerge that our family was more afraid of something than other families—at least, it seemed, more afraid than the mostly white middle-class families that formed the periphery of my childhood. Or perhaps our family’s fear was more specific. It was fear manifested as quiet contempt.

On that first trip in 2007, I bought a t-shirt from the souvenir vendors in Lviv’s Vernisage Market. I slept in it every night for a month because it was so soft. I saw nothing wrong with the shirt, and neither, apparently, did my father. In large purple letters it read:

Дякую тобі боже що я не Москаль.

Thanks be to God that I’m not a Moskal.

+++

My attempts to assign more complex vocabulary to this phenomenon have not felt entirely fruitful. This isn’t xenophobia, because after decades of occupation, oppression, murder, surveillance, a state-engineered famine, and the current ongoing invasion, my family’s distaste for Russia isn’t exactly irrational, as the definition suggests it should be. In Greek xenos refers to the strange, foreign, or unfamiliar, and that part isn’t so cut-and-dry either. Though western Ukrainians especially tend to “otherize” Russians, it is also true that by most visible markers—culture, religion, physical attributes, lifestyle—the groups aren’t so different at all. Both Busia and my father speak Russian in addition to Ukrainian. This is not a straightforward case of hating the unfamiliar.

Maybe bigotry is closer, but that term places special emphasis on opinions and ideas. Is it bigoted to dislike those who march through the world with imperial aims? Those who seem incapable of treating you without condescension?

Instead, it might best be characterized as enmity—“a very deep unfriendly feeling.” The word enmity conjures up a hostility of biblical proportions: “I will put enmity between you and the woman, between your offspring and hers.” In this analogy, the Russians are, of course, the dust-eating serpent. Enmity is a literary word, one that implies hatred left over from some long-ago circumstance. There is also an element of passivity. It has been this way since before we were born. It has always been like this. This is part of us.

Taras Shevchenko, the 19th-century poet who wrote Kateryna, meant the poem as an allegory. Soldier Ivan represents the Russian Empire, while Kateryna is the feminized, virginal, and subjugated Ukrainian nation. Shevchenko himself was born an imperial serf and didn’t have his freedom purchased until age 24, when, interestingly, a Russian poet was able to use his influence in Shevchenko’s favor. Luckily, Shevchenko was a talented artist.

Today Shevchenko is considered the father of modern Ukrainian literature and a useful national symbol. He remains highly venerated in Ukraine and his face appears on the 100 hryven bill. Busia and my father both have embroidered portraits of the mustachioed poet in their living rooms. Many Ukrainians do.

Cuprins

Contents Note on the Text The Village (Fugue) On Our Way Home from the Revolution Bloodlines (or, Although a Good Man, a Muscovite) Instructions for Parents in Upbringing Children Duck and Cover Word Portrait Veselka Article 54 of the Criminal Code of the Ukrainian SSR Samizdat The Village (Interlude) Encyclopedia of Earthly Things Swing State The Village (Reprise) I Saw the Sunshine, Melting The Village (Da Capo) Acknowledgments Notes Works Consulted

Descriere

Following the 2014 Ukrainian revolution, a child of the Ukrainian diaspora challenges her formative ideologies, considers innocence and complicity, and questions the roots of patriotism.