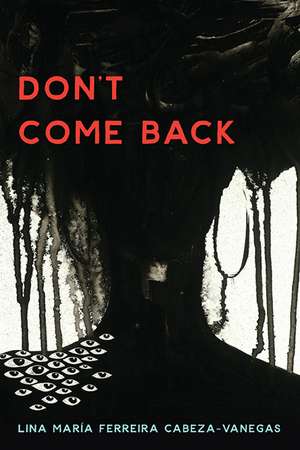

Don’t Come Back: 21st Century Essays

Autor Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegasen Limba Engleză Paperback – 20 ian 2017

In this collection of linked lyrical and narrative essays, experimental translations, and reinterpreted myths, Lina Maria Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas launches into an exploration of home and identity, family history and belonging, continually examining what it means to feel familiarity but never really feel at home.

Don’t Come Back intermixes translations of Spanish adages and adaptations of major Colombian myths with personal essays about growing up amidst violence, magic, and an unyielding Andean sun. Home is place and time and people and language and history, and none of these are ever set in stone. Attempting to reconcile the irreconcilable and translate the untranslatable—to move smoothly and cohesively between culture, language, and place—Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas is torn between spaces, between the aunt who begs her to return to Colombia and the mother who tells her, “There’s nothing here for you, Lina. Don’t come back.” Don’t Come Back is an exploration of home and identity that constantly asks, “If you really could go back, would you?”

Don’t Come Back intermixes translations of Spanish adages and adaptations of major Colombian myths with personal essays about growing up amidst violence, magic, and an unyielding Andean sun. Home is place and time and people and language and history, and none of these are ever set in stone. Attempting to reconcile the irreconcilable and translate the untranslatable—to move smoothly and cohesively between culture, language, and place—Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas is torn between spaces, between the aunt who begs her to return to Colombia and the mother who tells her, “There’s nothing here for you, Lina. Don’t come back.” Don’t Come Back is an exploration of home and identity that constantly asks, “If you really could go back, would you?”

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 216

Preț estimativ în valută:

27.62€ • 28.83$ • 22.86£

27.62€ • 28.83$ • 22.86£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814253953

ISBN-10: 0814253954

Pagini: 253

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814253954

Pagini: 253

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.38 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“In Don’t Come Back, Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas chronicles the immigrant’s ever-present tug of family and the familiar—what is left behind—and the equally strong pull of the new land with its lure of stability and security. Told in a lyrical and well-crafted style, Lina’s story asks readers to venture into the migrant heart’s dilemma—to go back or to stay in the new country.” —Norma E. Cantú

“Lina Ferreira is a shape-shifter of an essayist, never predictable. The worlds she inhabits are as big as legend and as small as a family in Colombia navigating the large and small cruelties of life. To try to define this book would be to kill it—the essays leap over formal boundaries in prose (by turns, moving, hilarious, and brutal) that can only ignite and inspire the imagination and intellect of the sympathetic reader.” —Robin Hemley, author of Nola: Memoir of Faith, Art, and Madness

“Don't Come Back is a gathering of images, memories, history, and myths that encircle the present in an attempt to make sense of a fragmented inheritance. Only Ferreira could make a dying cat, a torn and hanging lip, or a dissected lover beautiful. This book wounds and soothes in turn, disturbs and seduces at once.” —Angela Pelster-Wiebe, author of Limber (winner of the GLCA New Writers Award in Nonfiction)

“An extraordinary, shockingly good collection from a brilliant young writer, it perfectly fuses the carnal and the spectral, tenderness and unflinching grit, wry humor and recovered sorrow. This book exemplifies the role of imagination in nonfiction. Lina Ferreira’s sophisticated prose will surprise, delight, disconcert, entertain, dazzle, and move you.” —Phillip Lopate

Notă biografică

Lina María Ferreira Cabeza-Vanegas is the winner of the 2016 Rona Jaffe Foundation Writers’ Award, author of Drown/Sever/Sing, and Visiting Assistant Professor at The Ohio State University.

Extras

The hamsters were dead.

My sister still insists that I am to blame, and I may still wonder. Because this is certainly likely.

If you drop and throw a thing enough times, parts will eventually come loose inside it. Even if you name your hamster Little She-Rambo. Even if you slip on little bandoliers, and smear its face with mud, and drop it in a backyard-jungle obstacle course of dandelions and broken glass. Especially if you try to tie a miniature bandana around its head.

Words and reenactment are insufficient alchemy.

Tiny skulls need only tiny cracks for tiny swells and leaks to end tiny lives.

Regardless, it wasn’t me. (Probably.)

More likely it was the cold slipping in from under the door with a half-rotten board nailed to it. I remember, because I was there the night my father drove in the nails.

I held my green plastic hammer as he swung his, and I kept watch for the things I thought my father meant to keep out with wooden planks and bent nails. A board over a slit between the metal door and tile floor, wood like tape over rust-covered lips. And I turned my green hammer in my hands and waited—for the devil in the backyard, for the god of rats in the oven, for the men with rifles deep inside the mountains. For all of them to kick in the board, rip off the tape, and slip in through the crack beneath the door.

Mostly, however, “rats.” My father insisted, “Big rats, Lina.”

So, “Yes, Dad,” I said, “rats.” Except I said, “Si,” and I said, “Si, Papi,” because I was five and I didn’t speak English then and words are still insufficient alchemy—but here I am. “Yes, Dad, ratas.” And I spun my green hammer in my hands and planned on killing myself a rat. A good fat one, “Una ratisima ratota.”

Just for practice, just for when the others slipped in.

A brown-fur devil I saw peeking behind the tamarillo tree in the backyard one night, or the men in the news carrying AK-47s, or even the soldiers they shot at who stacked bricks of cocaine in front of the screen and seemed to me, back then, to be no different one from the other. Or, rather, the three-tailed god of rats my aunt Chiqui swears she saw once in the yard, covered in purple-black feathers and yellow spikes, running on two legs and leaping into the oven as it howled.

So I imagined it. Turned my hammer in my hands and heard the coconut skull crack of many heads beneath my swing. Just like my father did when the rats squeezed under the thin slit, swinging tiny feet and shaking black fur heads until they were inside and their little claws made plick-plack noises on the tile floor. Then he’d swing precisely and finally. A broomstick like a spear or a hammer like a sling. Swift and sure, down like a paperweight atop a flattened, soggy head while tails and feet twitched as if a mad wind were trying blow the whole thing away.

So in went the nails. To keep some things in and others out. Because some are pets and some are not, it’s hard to tie a leash around a tamarillo tree devil and ill-advised to let the men from the mountain in and lure the rat god out.

Though, of course, they all make it inside eventually. And I carry them with me all my life.

But not yet. Right there, right then, my father had a plan.

Hammer, wood, nails.

Out rats, in hamsters.

Out the conflict, in his children.

A man crouching beside a hamster cage swinging a hammer, driving in nails and keeping out rats.

“Because rats eat hamsters, too,” my mother explained. “They eat everything.” As she scrunched up her nose as if there were whiskers under her skin trying to sprout through her pores. “Disgusting.” And I turned my hammer again and again, picturing rats sitting cross-legged in a circle, pulling on hamster bodies like they were trying to fold bed sheets. One on each end, tug-tug-tugging until hamsters came apart and all went down rat hatches—legs, fur, whiskers, and bellies.

It was not the rats, however. It was the cold.

That’s what killed them. Because a wooden plank can only hold back so much.

My sister still insists that I am to blame, and I may still wonder. Because this is certainly likely.

If you drop and throw a thing enough times, parts will eventually come loose inside it. Even if you name your hamster Little She-Rambo. Even if you slip on little bandoliers, and smear its face with mud, and drop it in a backyard-jungle obstacle course of dandelions and broken glass. Especially if you try to tie a miniature bandana around its head.

Words and reenactment are insufficient alchemy.

Tiny skulls need only tiny cracks for tiny swells and leaks to end tiny lives.

Regardless, it wasn’t me. (Probably.)

More likely it was the cold slipping in from under the door with a half-rotten board nailed to it. I remember, because I was there the night my father drove in the nails.

I held my green plastic hammer as he swung his, and I kept watch for the things I thought my father meant to keep out with wooden planks and bent nails. A board over a slit between the metal door and tile floor, wood like tape over rust-covered lips. And I turned my green hammer in my hands and waited—for the devil in the backyard, for the god of rats in the oven, for the men with rifles deep inside the mountains. For all of them to kick in the board, rip off the tape, and slip in through the crack beneath the door.

Mostly, however, “rats.” My father insisted, “Big rats, Lina.”

So, “Yes, Dad,” I said, “rats.” Except I said, “Si,” and I said, “Si, Papi,” because I was five and I didn’t speak English then and words are still insufficient alchemy—but here I am. “Yes, Dad, ratas.” And I spun my green hammer in my hands and planned on killing myself a rat. A good fat one, “Una ratisima ratota.”

Just for practice, just for when the others slipped in.

A brown-fur devil I saw peeking behind the tamarillo tree in the backyard one night, or the men in the news carrying AK-47s, or even the soldiers they shot at who stacked bricks of cocaine in front of the screen and seemed to me, back then, to be no different one from the other. Or, rather, the three-tailed god of rats my aunt Chiqui swears she saw once in the yard, covered in purple-black feathers and yellow spikes, running on two legs and leaping into the oven as it howled.

So I imagined it. Turned my hammer in my hands and heard the coconut skull crack of many heads beneath my swing. Just like my father did when the rats squeezed under the thin slit, swinging tiny feet and shaking black fur heads until they were inside and their little claws made plick-plack noises on the tile floor. Then he’d swing precisely and finally. A broomstick like a spear or a hammer like a sling. Swift and sure, down like a paperweight atop a flattened, soggy head while tails and feet twitched as if a mad wind were trying blow the whole thing away.

So in went the nails. To keep some things in and others out. Because some are pets and some are not, it’s hard to tie a leash around a tamarillo tree devil and ill-advised to let the men from the mountain in and lure the rat god out.

Though, of course, they all make it inside eventually. And I carry them with me all my life.

But not yet. Right there, right then, my father had a plan.

Hammer, wood, nails.

Out rats, in hamsters.

Out the conflict, in his children.

A man crouching beside a hamster cage swinging a hammer, driving in nails and keeping out rats.

“Because rats eat hamsters, too,” my mother explained. “They eat everything.” As she scrunched up her nose as if there were whiskers under her skin trying to sprout through her pores. “Disgusting.” And I turned my hammer again and again, picturing rats sitting cross-legged in a circle, pulling on hamster bodies like they were trying to fold bed sheets. One on each end, tug-tug-tugging until hamsters came apart and all went down rat hatches—legs, fur, whiskers, and bellies.

It was not the rats, however. It was the cold.

That’s what killed them. Because a wooden plank can only hold back so much.