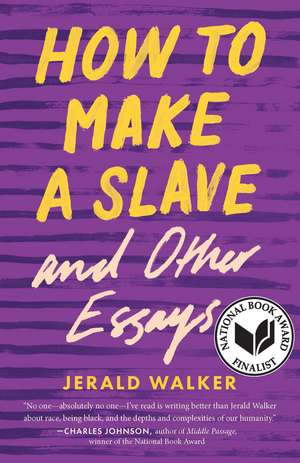

How to Make a Slave and Other Essays: 21st Century Essays

Autor Jerald Walkeren Limba Engleză Paperback – 30 oct 2020 – vârsta ani

Winner, Massachusetts Book Award

A Book of the Year pick from Kirkus, BuzzFeed, and Literary Hub

“The essays in this collection are restless, brilliant and short.…The brevity suits not just Walker’s style but his worldview, too.…Keeping things quick gives him the freedom to move; he can alight on a truth without pinning it into place.” —Jennifer Szalai, the New York Times

For the black community, Jerald Walker asserts in How to Make a Slave, “anger is often a prelude to a joke, as there is broad understanding that the triumph over this destructive emotion lay in finding its punchline.” It is on the knife’s edge between fury and farce that the essays in this exquisite collection balance. Whether confronting the medical profession’s racial biases, considering the complicated legacy of Michael Jackson, paying homage to his writing mentor James Alan McPherson, or attempting to break free of personal and societal stereotypes, Walker elegantly blends personal revelation and cultural critique. The result is a bracing and often humorous examination by one of America’s most acclaimed essayists of what it is to grow, parent, write, and exist as a black American male. Walker refuses to lull his readers; instead his missives urge them to do better as they consider, through his eyes, how to be a good citizen, how to be a good father, how to live, and how to love.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 156

Preț estimativ în valută:

19.85€ • 20.72$ • 16.43£

19.85€ • 20.72$ • 16.43£

Carte indisponibilă temporar

Doresc să fiu notificat când acest titlu va fi disponibil:

Se trimite...

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814255995

ISBN-10: 081425599X

Pagini: 152

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 081425599X

Pagini: 152

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.2 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“The essays in this collection are restless, brilliant and short.…The brevity suits not just Walker’s style but his worldview, too.…Keeping things quick gives him the freedom to move; he can alight on a truth without pinning it into place.” —Jennifer Szalai, the New York Times

“[These] powerful essays offer an incisive glimpse into life as a Black man in America. Walker demonstrates the keen intellect and direct style that characterized his acclaimed 2010 memoir, Street Shadows….Crafted with honesty and wry comedic flair, these essays are both engaging and enraging.” —Kirkus (starred review)

“Walker … delivers a stylish and thought-provoking collection of reflections on his personal and professional life.…[His] rich compilation adds up to a rewardingly insightful self-portrait that reveals how one man relates to various aspects of his identity.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“In these absorbing essays, Jerald Walker adds race to the commonplace (a little girl helping her younger brother with his homework, a job interview, a family dining out, a teenager crashing the family car) and shows us something knotty, fraught, and unforgettable, not just about race and the commonplace, ‘living while black,’ but about living while human. Walker is furious and funny. He is talking to himself about his life and allows us to listen in.”—Judges’ citation, 2020 National Book Awards

“How to Make a Slave and Other Essays by South Side native Jerald Walker was one of the year’s smartest sleepers, an often hilarious roundup of stories about the obliviousness of white liberals, race and restaurant seating, and the writer’s own mentor.”—Chicago Tribune

“These aren’t essays. This is hypnosis, a spell of enchantment cast over the reader by a masterful writer whose crystal-clear vision is not only original but revelatory. I laughed out loud, nodded at Jerald Walker’s delivery of so much truth, and just shook my head at how gracefully he achieves so much so quickly in every piece in How to Make a Slave. All I can say is, ‘Wow.’ And you can’t just consume one; you’ll find yourself gobbling down every essay here and hungering for more. No one—absolutely no one—I’ve read is writing better than Jerald Walker about race, being black, and the depths and complexities of our humanity.”

—Charles Johnson, author of Middle Passage, winner of the National Book Award

“This piercing and restless collection slices through this country’s agitated racial landscape with the tenacity of a thunderbolt. Walker manages to be all of us—we are all the college English department’s pet token, we are all the potential Whole Foods crime wave, we are all the Negro middle American agonizing over a return trip to the implosive inner city from whence we came. These fresh, revelatory snippets of black life deserve a rollicking collective Amen! and an audience of both the converted and the curious.”

—Patricia Smith, author of Incendiary Art

“I’ve been waiting for this, the first collection of essays by one of our best essayists, for years. Jerald Walker’s How to Make a Slave is notable for its persistence of vision. These essays are relentlessly humane even as they stare into America’s split, racist heart. And like America and Americans, this book is both funny and fucked up, and neither can exist without the other.”

—Ander Monson, author of I Will Take the Answer

“[These] powerful essays offer an incisive glimpse into life as a Black man in America. Walker demonstrates the keen intellect and direct style that characterized his acclaimed 2010 memoir, Street Shadows….Crafted with honesty and wry comedic flair, these essays are both engaging and enraging.” —Kirkus (starred review)

“Walker … delivers a stylish and thought-provoking collection of reflections on his personal and professional life.…[His] rich compilation adds up to a rewardingly insightful self-portrait that reveals how one man relates to various aspects of his identity.”—Publishers Weekly (starred review)

“In these absorbing essays, Jerald Walker adds race to the commonplace (a little girl helping her younger brother with his homework, a job interview, a family dining out, a teenager crashing the family car) and shows us something knotty, fraught, and unforgettable, not just about race and the commonplace, ‘living while black,’ but about living while human. Walker is furious and funny. He is talking to himself about his life and allows us to listen in.”—Judges’ citation, 2020 National Book Awards

“How to Make a Slave and Other Essays by South Side native Jerald Walker was one of the year’s smartest sleepers, an often hilarious roundup of stories about the obliviousness of white liberals, race and restaurant seating, and the writer’s own mentor.”—Chicago Tribune

“These aren’t essays. This is hypnosis, a spell of enchantment cast over the reader by a masterful writer whose crystal-clear vision is not only original but revelatory. I laughed out loud, nodded at Jerald Walker’s delivery of so much truth, and just shook my head at how gracefully he achieves so much so quickly in every piece in How to Make a Slave. All I can say is, ‘Wow.’ And you can’t just consume one; you’ll find yourself gobbling down every essay here and hungering for more. No one—absolutely no one—I’ve read is writing better than Jerald Walker about race, being black, and the depths and complexities of our humanity.”

—Charles Johnson, author of Middle Passage, winner of the National Book Award

“This piercing and restless collection slices through this country’s agitated racial landscape with the tenacity of a thunderbolt. Walker manages to be all of us—we are all the college English department’s pet token, we are all the potential Whole Foods crime wave, we are all the Negro middle American agonizing over a return trip to the implosive inner city from whence we came. These fresh, revelatory snippets of black life deserve a rollicking collective Amen! and an audience of both the converted and the curious.”

—Patricia Smith, author of Incendiary Art

“I’ve been waiting for this, the first collection of essays by one of our best essayists, for years. Jerald Walker’s How to Make a Slave is notable for its persistence of vision. These essays are relentlessly humane even as they stare into America’s split, racist heart. And like America and Americans, this book is both funny and fucked up, and neither can exist without the other.”

—Ander Monson, author of I Will Take the Answer

Notă biografică

Jerald Walker is the author of The World in Flames: A Black Boyhood in a White Supremacist Doomsday Cult and Street Shadows: A Memoir of Race, Rebellion, and Redemption, winner of the 2011 PEN New England Award for Nonfiction. He has published in magazines such as Creative Nonfiction, Harvard Review, Missouri Review, River Teeth, Mother Jones, Iowa Review, and Oxford American, and he has been widely anthologized, including four times in The Best American Essays. The recipient of James A. Michener and National Endowment for the Arts fellowships, Walker is Professor of Creative Writing at Emerson College.

Extras

I was at a Christmas party with a man who wanted me to hate him. I should hate all whites, he felt, for what they have done to me. I thought hard about what whites have done to me. I was forty, old enough to have accumulated a few unpleasant racial encounters, but nothing of any lasting significance came to mind. The man was aston- ished at this response. “How about slavery?” he asked. I explained, as politely as I could, that I had not been a slave. “But you feel its effects,” he snapped. “Racism, dis- crimination, and prejudice will always be a problem for you in this country. White people,” he insisted, “are youroppressors.” I glanced around the room, just as one of my oppressors happened by. She was holding a tray of cana- pés. She offered me one. I asked the man if, as a form of reparations, I should take two.

It was midway through my third year in academia. I had survived mountains of papers, apathetic students, cantankerous colleagues, boring meetings, sleep deprivation, and two stalkers, and now I was up against a man who had been mysteriously transported from 1962. He even looked the part, with lavish sideburns and solid, black-rimmed glasses. He wasn’t an academic, but rather the spouse of one. In fact, he had no job at all, a dual act of defiance, he felt, against a patriarchal and capitalistic society. He was a fun person to talk with, especially if, like me, you enjoyed driving white liberals up the wall. And the surest way to do that, if you were black, was to deny them the chance to pity you.

He’d spotted me thirty minutes earlier while I stood alone at the dining room table, grazing on various appe- tizers. My wife, Brenda, had drifted off somewhere, and the room buzzed with pockets of conversation and laughter. The man joined me. I accepted his offer of a gin and tonic. We talked local politics for a moment, or rather he talked and I listened, because, being relatively new to this small town, it wasn’t something I knew much about, before moving on to the Patriots, our kids, and finally my classes. He was particularly interested in my African Amer- ican Literature course. “Did you have any black students?” he inquired.

“We started with two,” I said, “but ended with twenty- eight.” I let his puzzled expression linger until I’d eaten a stuffed mushroom. “Everyone who takes the course has to agree to be black for the duration of the semester.”

“Really?” he asked, laughing. “What do they do, smear their faces with burnt cork?”

“Not a bad idea,” I said. “But for now, they simply have to think like blacks, but in a way different from what they probably expect.” I told him that black literature is often approached as records of oppression, but that my stu- dents don’t focus on white cruelty but rather its flip side: black courage. “After all,” I continued, “slaves and their immediate descendants were by and large heroic, not pathetic, or I wouldn’t be standing here.”

The man was outraged. “You’re letting whites off the hook,” he said. “You’re absolving them of responsibility, of the obligation to atone for past and present wrongs . . .” He went on in this vein for a good while, and I am pleased to say that I goaded him until he stormed across the room and stood with his wife, who, after he’d spoken with her, glanced in my direction to see, no doubt, a traitor to the black race. That was unfortunate. I’d like to think I betray whites too.

It was midway through my third year in academia. I had survived mountains of papers, apathetic students, cantankerous colleagues, boring meetings, sleep deprivation, and two stalkers, and now I was up against a man who had been mysteriously transported from 1962. He even looked the part, with lavish sideburns and solid, black-rimmed glasses. He wasn’t an academic, but rather the spouse of one. In fact, he had no job at all, a dual act of defiance, he felt, against a patriarchal and capitalistic society. He was a fun person to talk with, especially if, like me, you enjoyed driving white liberals up the wall. And the surest way to do that, if you were black, was to deny them the chance to pity you.

He’d spotted me thirty minutes earlier while I stood alone at the dining room table, grazing on various appe- tizers. My wife, Brenda, had drifted off somewhere, and the room buzzed with pockets of conversation and laughter. The man joined me. I accepted his offer of a gin and tonic. We talked local politics for a moment, or rather he talked and I listened, because, being relatively new to this small town, it wasn’t something I knew much about, before moving on to the Patriots, our kids, and finally my classes. He was particularly interested in my African Amer- ican Literature course. “Did you have any black students?” he inquired.

“We started with two,” I said, “but ended with twenty- eight.” I let his puzzled expression linger until I’d eaten a stuffed mushroom. “Everyone who takes the course has to agree to be black for the duration of the semester.”

“Really?” he asked, laughing. “What do they do, smear their faces with burnt cork?”

“Not a bad idea,” I said. “But for now, they simply have to think like blacks, but in a way different from what they probably expect.” I told him that black literature is often approached as records of oppression, but that my stu- dents don’t focus on white cruelty but rather its flip side: black courage. “After all,” I continued, “slaves and their immediate descendants were by and large heroic, not pathetic, or I wouldn’t be standing here.”

The man was outraged. “You’re letting whites off the hook,” he said. “You’re absolving them of responsibility, of the obligation to atone for past and present wrongs . . .” He went on in this vein for a good while, and I am pleased to say that I goaded him until he stormed across the room and stood with his wife, who, after he’d spoken with her, glanced in my direction to see, no doubt, a traitor to the black race. That was unfortunate. I’d like to think I betray whites too.

Cuprins

Contents

How to Make a Slave

Dragon Slayers

Before Grief

Inauguration

Kaleshion

The Heritage Room

Unprepared

Feeding Pigeons

Breathe

The Heart

Balling

Testimony

Smoke

Wars

Simple

The Designated Driver

Strippers

Thieves

Once More to the Ghetto

Race Stories

Advice to a Family Man

Acknowledgments

How to Make a Slave

Dragon Slayers

Before Grief

Inauguration

Kaleshion

The Heritage Room

Unprepared

Feeding Pigeons

Breathe

The Heart

Balling

Testimony

Smoke

Wars

Simple

The Designated Driver

Strippers

Thieves

Once More to the Ghetto

Race Stories

Advice to a Family Man

Acknowledgments

Descriere

A bracing and often humorous examination by one of America’s most acclaimed essayists of what it is to grow, parent, write, and exist as a black American male.