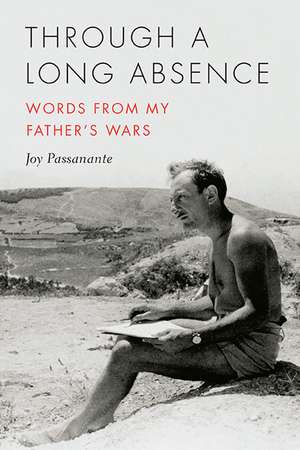

Through a Long Absence: Words from My Father's Wars: 21st Century Essays

Autor Joy Passananteen Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 aug 2017

A 2017 Foreword INDIES Book of the Year Silver Winner for Biography

Against the backdrop of World War II, Joy Passanante’s touching new book, Through a Long Absence: Words from My Father’s Wars, is the saga of a wartime medical unit, a passionate long-distance love, the making of a surgeon, and two first-generation American families. Told through her father’s eyes—drawing on hundreds of his letters to his beloved wife, his four-volume wartime diary, and his paintings—Passanante masterfully recreates his wartime journey and physically retraces his steps more than sixty years later in an attempt to understand a time in her parents’ lives that they’d spoken about very little.

More than just a World War II story, Through a Long Absence delves into one man’s past to explore his personal wars: a stint as a child bootlegger, a marriage between newlyweds separated by continents and strained by years apart, and his struggle late in life with his own mind. The narrative propels readers to surprising places—from a freight train through North Africa to an underground St. Louis distillery during Prohibition, from a young couple’s forbidden courtship to the chaos of surgical tents under fire in Normandy, from an underground trove of priceless artwork hidden by the Nazis to Jewish New Year services in Paris a week after its liberation. Through a Long Absence is a love story, an honest look into one man’s life, and a daughter’s moving quest to rediscover her father years later through his own words.

Against the backdrop of World War II, Joy Passanante’s touching new book, Through a Long Absence: Words from My Father’s Wars, is the saga of a wartime medical unit, a passionate long-distance love, the making of a surgeon, and two first-generation American families. Told through her father’s eyes—drawing on hundreds of his letters to his beloved wife, his four-volume wartime diary, and his paintings—Passanante masterfully recreates his wartime journey and physically retraces his steps more than sixty years later in an attempt to understand a time in her parents’ lives that they’d spoken about very little.

More than just a World War II story, Through a Long Absence delves into one man’s past to explore his personal wars: a stint as a child bootlegger, a marriage between newlyweds separated by continents and strained by years apart, and his struggle late in life with his own mind. The narrative propels readers to surprising places—from a freight train through North Africa to an underground St. Louis distillery during Prohibition, from a young couple’s forbidden courtship to the chaos of surgical tents under fire in Normandy, from an underground trove of priceless artwork hidden by the Nazis to Jewish New Year services in Paris a week after its liberation. Through a Long Absence is a love story, an honest look into one man’s life, and a daughter’s moving quest to rediscover her father years later through his own words.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 211

Preț estimativ în valută:

26.89€ • 28.15$ • 22.25£

26.89€ • 28.15$ • 22.25£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254240

ISBN-10: 0814254241

Pagini: 280

Ilustrații: 13 b&w

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814254241

Pagini: 280

Ilustrații: 13 b&w

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 25 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“Armed with a trove of letters . . . the latter-day Passanante explores her father’s recollection of events and retraces his steps on some parts of the journey. She has a good eye for the telling detail.” —Kirkus Reviews

“This intimate and epic portrait of a father from a daughter is both an act of love and of memory, lost and miraculously found. It’s absorbing and affecting in every detail. Through a Long Absence is one from the heart. It’ll take a piece out of you.” —Peter Travers, Rolling Stone

“In this meticulously researched and intricately imagined story, Joy Passanante honors—in the best possible way—the love her parents discovered in their youth, maintained through the long absence of war, and carried to the grave (and one imagines, beyond it). Elegiac and deeply loving in tone, this daughter’s re-creation of her parents’ lives also serves as a reminder of the toll war takes on the human souls of the survivors.” —Pam Houston, author of Contents May Have Shifted

“With skill and devotion, Joy Passanante follows the trail of her father’s youth working for a bootlegger, his passionate courtship of her mother, and his years as a U.S. Army doctor overseas and under fire in World War II. Her book is a remarkable and moving tribute to family love and tradition.” —Alison Lurie, Pulitzer Prize winner

“With poignancy and grace, Joy Passanante has written a love story for the ages: the war-time love between her father and mother; the love the author feels for her parents, her husband, and her own children; and the love she feels for the story that has bound and defined them. With unbridled affection and admiration, Passanante follows the hero’s journey her father undertook as a young husband, soldier, and physician. Her poet’s eye for the telling detail infuses every diary entry, letter, and memory with such vivid imagery and emotion that we find ourselves not only retracing but reliving the hardships of war, just as the author does as she travels back to the battlefields and towns that shaped the man her father would become. A love story, yes, but this book is also a love letter to the author’s father and the many people in war-torn countries whose lives he touched and whose lives touched him. There is a unity of purpose and spirit in this book that will speak to the children and grandchildren of the Greatest Generation. We come away reminded of the focus and sacrifice that, though elevated to myth, happened at the level of the individual. The treasury of memories this book contains is a gift that informs and inspires not only the author and her family but all of us in our shared experience of fear, loss, hope, devotion, and survival. —Kim Barnes, Pulitzer Prize Finalist for In the Wilderness: Coming of Age in Unknown Country

“Through a Long Absence is bursting at the seams with the real stuff of life. War, love, loss, family—all these play out in the classic American context of an immigrant striving toward that hard-won place in the sun. Joy Passanante’s wise and passionate memoir is a moving testament not just to her family but also to the deep thing in all of us that keeps turning–and, on some level, never stops yearning—for the people and places in our past that are the soul’s true home.” —Ben Fountain, National Book Critics Circle Award winner

“With insight and compassion, Joy Passanante embarks on a journey to investigate one of the great and often unsettling mysteries of life—who were our parents before we came into their lives?” —John Sayles, novelist and filmmaker

Notă biografică

Joy Passanante has been publishing in three genres for five decades. She is the author of The Art of Absence, My Mother’s Lovers, and Sinning in Italy.

Extras

Chevy Chase, St. Louis, Missouri, the 1990s

Every morning of my yearly summer visit, before the sun could warm the water, I’d wake up in the room of my youth in the bed with the blue ball-fringed canopy and dust ruffle and immediately don my bathing suit. I’d sail downstairs, out the recreation room door, toward the pool. By then, my father, Bart Passanante, had already hosed down the patio and tile that rimmed the water and moved the redwood lounge I’d been occupying for a score or so of summer visits. He’d place the lounge close to but not under the shade of the Japanese maple in the pool garden. That way, he could maximize my sunlight before the heat and humidity could sink their teeth into my skin, scorch and drain me in turns. As the heat deepened, he’d pull my perch into the shade so that my view would be the daylilies that trumpeted out every day with the precision of a metronome.

Whenever he entered the pool garden on his rounds with his bucket and hose and rubber fishing boots and hoes and weeders, I stared at him, relishing his idiosyncrasies. He poked his grass here and there with what looked like a pronged stick. When he glanced up from his work and saw me looking at him, he dimpled up. He paused from time to time to straighten his back and admire his zinnias and cacti garden, and, if I was there in June, the daisies, which were my wedding flower and which he always timed to bloom when I was back in St. Louis. Occasionally he gestured to show me a plump worm of the sort he used to dig up when he took me fishing, or a sprig of poison ivy. We smiled at each other, and I was happy to be in his presence.

From this seamless-seeming bank of pleasure-days, my memory proffers me two hours in particular, both scenes tinted with the preternatural brilliance of Technicolor. Scene 1: I am perched on the lounge next to a small redwood table, a splintered leg of which my father has bound up with a generous hunk of the adhesive tape he once used in dressing the wounds of his patients. He is nearly deaf by then, and I usually need a pad and pencil to communicate clearly. Though I always keep these supplies at hand when I know I will be with him, and they are now on the table, I seldom use them. We never seemed to need to say much to each other. Writing away on an idea for a novel, I’m only vaguely aware that he has ducked into the house. When he returns to the patio, he’s toting a stack of worn-looking books. He sets aside my notepad and pencil and lays down the books. At first I don’t recognize them.

“Did I ever show you my war diaries?” he asks, his voice a little uncertain since he can’t hear how loud he’s talking. I shake my head, feeling the sting of shame at remembering a Christmas night when our annual holiday party was waning, when he wanted my sisters and me and all our friends to listen to him read from his diaries, and we, deafened by our youthful narcissism, chose not to. Shame, too, at the fact that I am relieved that he doesn’t seem to remember. Knowing what I know now, I can hardly believe that I felt relief at the desertion of his memory.

“Would you like to see these?” he asks sheepishly.

“I’d love to,” I say, raising my volume. I pluck a book from the pile. It’s not a diary but a photo album with black-and-whites meticulously organized and labeled, stuck with black photo corners. As I begin to thumb through it, he beams, then resumes his tour of duty around his lawn.

I spend the better part of the month immersed in these books, and, sometimes when I glance at him puttering in his garden, rubbing the moisture from my eyes.

Scene 2: On the last day of that summer’s visit, Diary Volume 4 propped up on my knees, he comes up behind me, startling me.

“I don’t suppose you would want to have these someday, would you?” he asks, pointing to the pile on the table. I look askance. How could he even think I wouldn’t want them?

“Of course,” I shout so he can hear. “We all would. Anyone would.”

He nods, though I’m not sure he has understood my exact words. But he has certainly read my expression.

“Well, if you want them, I’d like you to have them,” he says. Since he can no longer hear his own voice clearly, his words emerge a little unsteady, and some of the syllables crack and lilt up a timbre. Before I can rise from the lounge to throw my arms around his neck and yell directly into his ear, he disappears around the fence.

He still had his memory then, and I like to think he remembered giving me that gift of gifts that afternoon under the Japanese maple even after he could no longer remember my name.

Every morning of my yearly summer visit, before the sun could warm the water, I’d wake up in the room of my youth in the bed with the blue ball-fringed canopy and dust ruffle and immediately don my bathing suit. I’d sail downstairs, out the recreation room door, toward the pool. By then, my father, Bart Passanante, had already hosed down the patio and tile that rimmed the water and moved the redwood lounge I’d been occupying for a score or so of summer visits. He’d place the lounge close to but not under the shade of the Japanese maple in the pool garden. That way, he could maximize my sunlight before the heat and humidity could sink their teeth into my skin, scorch and drain me in turns. As the heat deepened, he’d pull my perch into the shade so that my view would be the daylilies that trumpeted out every day with the precision of a metronome.

Whenever he entered the pool garden on his rounds with his bucket and hose and rubber fishing boots and hoes and weeders, I stared at him, relishing his idiosyncrasies. He poked his grass here and there with what looked like a pronged stick. When he glanced up from his work and saw me looking at him, he dimpled up. He paused from time to time to straighten his back and admire his zinnias and cacti garden, and, if I was there in June, the daisies, which were my wedding flower and which he always timed to bloom when I was back in St. Louis. Occasionally he gestured to show me a plump worm of the sort he used to dig up when he took me fishing, or a sprig of poison ivy. We smiled at each other, and I was happy to be in his presence.

From this seamless-seeming bank of pleasure-days, my memory proffers me two hours in particular, both scenes tinted with the preternatural brilliance of Technicolor. Scene 1: I am perched on the lounge next to a small redwood table, a splintered leg of which my father has bound up with a generous hunk of the adhesive tape he once used in dressing the wounds of his patients. He is nearly deaf by then, and I usually need a pad and pencil to communicate clearly. Though I always keep these supplies at hand when I know I will be with him, and they are now on the table, I seldom use them. We never seemed to need to say much to each other. Writing away on an idea for a novel, I’m only vaguely aware that he has ducked into the house. When he returns to the patio, he’s toting a stack of worn-looking books. He sets aside my notepad and pencil and lays down the books. At first I don’t recognize them.

“Did I ever show you my war diaries?” he asks, his voice a little uncertain since he can’t hear how loud he’s talking. I shake my head, feeling the sting of shame at remembering a Christmas night when our annual holiday party was waning, when he wanted my sisters and me and all our friends to listen to him read from his diaries, and we, deafened by our youthful narcissism, chose not to. Shame, too, at the fact that I am relieved that he doesn’t seem to remember. Knowing what I know now, I can hardly believe that I felt relief at the desertion of his memory.

“Would you like to see these?” he asks sheepishly.

“I’d love to,” I say, raising my volume. I pluck a book from the pile. It’s not a diary but a photo album with black-and-whites meticulously organized and labeled, stuck with black photo corners. As I begin to thumb through it, he beams, then resumes his tour of duty around his lawn.

I spend the better part of the month immersed in these books, and, sometimes when I glance at him puttering in his garden, rubbing the moisture from my eyes.

Scene 2: On the last day of that summer’s visit, Diary Volume 4 propped up on my knees, he comes up behind me, startling me.

“I don’t suppose you would want to have these someday, would you?” he asks, pointing to the pile on the table. I look askance. How could he even think I wouldn’t want them?

“Of course,” I shout so he can hear. “We all would. Anyone would.”

He nods, though I’m not sure he has understood my exact words. But he has certainly read my expression.

“Well, if you want them, I’d like you to have them,” he says. Since he can no longer hear his own voice clearly, his words emerge a little unsteady, and some of the syllables crack and lilt up a timbre. Before I can rise from the lounge to throw my arms around his neck and yell directly into his ear, he disappears around the fence.

He still had his memory then, and I like to think he remembered giving me that gift of gifts that afternoon under the Japanese maple even after he could no longer remember my name.

Descriere

Based on his emotional, honest, and occasionally humorous letters to his wife during World War II, Joy Passanante’s Through a Long Absence: Words from My Father’s Wars tells the story of one man coming of age as a young surgeon performing operations in tents under fire, struggling in St. Louis as a child bootlegger and the son of Sicilian immigrants, and taking up a passionate love affair with his Jewish wife.