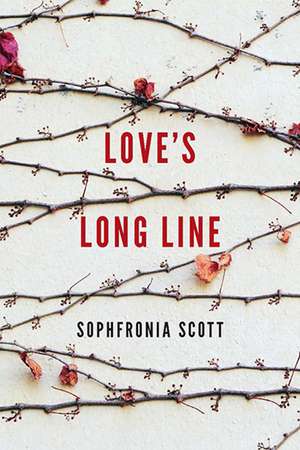

Love’s Long Line: 21st Century Essays

Autor Sophfronia Scotten Limba Engleză Paperback – 10 feb 2018

Sophfronia Scott turns an unflinching eye on her life to deliver a poignant collection of essays ruminating on faith, motherhood, race, and the search for meaningful connection in an increasingly disconnected world.

In Love’s Long Line, Scott contemplates what her son taught her about grief after the shootings at his school, Sandy Hook Elementary; how a walk with Lena Horne became a remembrance of love for Scott’s illiterate and difficult steelworker father; the unexpected heartache of being a substitute school bus driver; and the satisfying fantasy of paying off a mortgage. Scott’s road is also a spiritual journey ignited by an exploration of her first name, the wonder of her physical being, and coming to understand why her soul must dance like Saturday Night Fever’s Tony Manero.

Inspired by Annie Dillard’s observation in Holy the Firm that we all “reel out love’s long line alone . . . like a live wire loosed in space to longing and grief everlasting,” Scott’s essays acknowledge the loneliness, longing, and grief exacted by a fearless engagement with the everyday world. But she shows that by holding the line, there is an abundance of joy and forgiveness and grace to be had as well.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 221

Preț estimativ în valută:

28.15€ • 29.47$ • 23.29£

28.15€ • 29.47$ • 23.29£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 01-07 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254639

ISBN-10: 0814254632

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814254632

Pagini: 240

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.27 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“Sophfronia Scott’s beautiful collection of essays is wise and ruminative, a pleasure to read. Whether she’s writing of the deeply personal or the culture at large, she makes us care and gives us a good long look at what this loud and calamitous world would have us ignore: hope.” —Bret Lott

“Sophfronia Scott has written a book of truth and grace. Clear-sighted in every way, Love’s Long Line has much to teach us about family, about the challenges the world gives us, about the journeys we make toward forgiveness. This is a book for the mind and the soul.” —Lee Martin, author of Pulitzer Prize finalist The Bright Forever

Notă biografică

Sophfronia Scott is a novelist and former writer for Time and People. She is the author of four books of fiction and nonfiction, including Unforgivable Love and All I Need to Get By.

Extras

In the weeks following the shootings at my son’s school, the children of Sandy Hook Elementary did not play outside. That January they started classes in an old middle school building the next town over. “Mothballed,” officials had called it, forsaken for a new facility, constructed next door, several years earlier. To accommodate the Sandy Hook children the old building needed to be brought up to code. And, since it had been a school for older students, it had no playground. The work on a new playground began despite the cold. Tain, then eight and a third grader, was excited by the prospect of a fresh slide and untouched swings. He would come home and report on the progress he viewed in glimpses from the school bus or classroom windows. But I got the sense that no one was in a hurry to have the children outside. Police officers stood vigilant at the school’s entrance and also at the driveway near the road. The prying eyes of the media, so hot in the days after the shootings they threatened to melt every ounce of patience and resolve the town had left, still roamed. As for the children—many were sensitive to loud noises, and some were afraid to go upstairs in their own homes.

After a few weeks Tain grew tired of the indoor recesses, and one day at home he told me he wanted to play outside. I was surprised—he didn’t ask me or his father to go out with him, and I knew he didn’t particularly like playing outside alone in the cold. But I was glad he wanted to go. I helped him bundle up in his coat and boots. I pulled a knit cap down over his thick black curls and drew a stick of balm over his pink lips. Then he went out into the yard. I took my laptop into the family room where I could keep an eye on him through the windows while I worked. At first he walked around in the yard, stomping lightly as though he were testing the frozen ground beneath his feet. He went over to the swing set and slid down the slide and sat on one of the blue plastic swings. I focused on my computer screen and wrote a few lines. When I looked up again Tain was in the woods, climbing the stony slope behind our house. I knew where he was going—to the plateau where a huge fallen tree served as both bridge and fort. In the summer the leaves of the trees close off this space from the view of the house and it becomes a giant, adventure-ready playroom. I usually sit on the deck and monitor Tain and his friends by listening. On that cold day I moved my laptop to the kitchen table and cracked open the sliding glass doors off the deck just enough so I could hear him. After a while Tain’s voice did come floating through the screen door. He was kind of singing, kind of talking, and I smiled, thinking he was talking to himself. He seemed to be telling a story from the Club Penguin game he often played on our kitchen computer. But who was he telling it to? Then I realized—maybe he wasn’t really alone.

This was how he had played with his friend Ben. Ben was among the young victims of the shooting, his classroom just a few hundred feet down the hall from Tain’s. Was Tain in search of his friend in their special place in the woods? Could he feel Ben’s presence as he walked over the smooth trunk of the fallen tree? I felt a strange comfort in the possibility. I knew he was grieving and if he could connect in some way with a feeling of Ben then that would tell me he was working his own process. Only Tain knew and knows the depth of his loss and the shock of realizing a child even younger than himself can die. He has few words for the magnitude of what’s happened, and perhaps it is adult folly to think I can accurately describe a void where love once stood. But I can ponder and I can hope. If he was walking through the soft shadows of his grief, even if accompanied by a kind of ghost, I knew he would have the best chance of emerging on the other side.

After a few weeks Tain grew tired of the indoor recesses, and one day at home he told me he wanted to play outside. I was surprised—he didn’t ask me or his father to go out with him, and I knew he didn’t particularly like playing outside alone in the cold. But I was glad he wanted to go. I helped him bundle up in his coat and boots. I pulled a knit cap down over his thick black curls and drew a stick of balm over his pink lips. Then he went out into the yard. I took my laptop into the family room where I could keep an eye on him through the windows while I worked. At first he walked around in the yard, stomping lightly as though he were testing the frozen ground beneath his feet. He went over to the swing set and slid down the slide and sat on one of the blue plastic swings. I focused on my computer screen and wrote a few lines. When I looked up again Tain was in the woods, climbing the stony slope behind our house. I knew where he was going—to the plateau where a huge fallen tree served as both bridge and fort. In the summer the leaves of the trees close off this space from the view of the house and it becomes a giant, adventure-ready playroom. I usually sit on the deck and monitor Tain and his friends by listening. On that cold day I moved my laptop to the kitchen table and cracked open the sliding glass doors off the deck just enough so I could hear him. After a while Tain’s voice did come floating through the screen door. He was kind of singing, kind of talking, and I smiled, thinking he was talking to himself. He seemed to be telling a story from the Club Penguin game he often played on our kitchen computer. But who was he telling it to? Then I realized—maybe he wasn’t really alone.

This was how he had played with his friend Ben. Ben was among the young victims of the shooting, his classroom just a few hundred feet down the hall from Tain’s. Was Tain in search of his friend in their special place in the woods? Could he feel Ben’s presence as he walked over the smooth trunk of the fallen tree? I felt a strange comfort in the possibility. I knew he was grieving and if he could connect in some way with a feeling of Ben then that would tell me he was working his own process. Only Tain knew and knows the depth of his loss and the shock of realizing a child even younger than himself can die. He has few words for the magnitude of what’s happened, and perhaps it is adult folly to think I can accurately describe a void where love once stood. But I can ponder and I can hope. If he was walking through the soft shadows of his grief, even if accompanied by a kind of ghost, I knew he would have the best chance of emerging on the other side.

Descriere

A rumination on faith, motherhood, race, and human connection after the shooting at her son’s school, Sandy Hook Elementary.