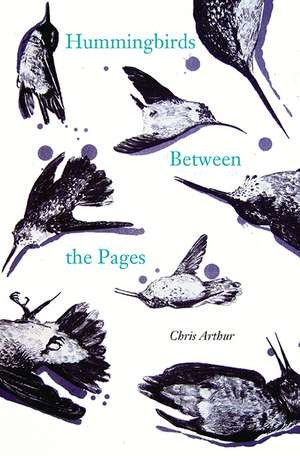

Hummingbirds Between the Pages: 21st Century Essays

Autor Chris Arthuren Limba Engleză Paperback – 23 iul 2018

In his latest collection, Hummingbirds Between the Pages, prizewinning Irish essayist Chris Arthur muses on subjects ranging from Charles Darwin’s killing of a South American fox to the carnal music sounding in a statue of the Buddha, from how Egyptian seashells contain echoes of World War II to a child’s first encounter with death. Whether he’s looking at skipping stones, old photographs, butterflies, the resonance of a remembered phrase, or being questioned at an army checkpoint during Northern Ireland’s Troubles, what gives these unorthodox meditations their appeal is the way in which—with striking lyricism—they tap into unexpected seams of meaning and mystery in our everyday terrain. Arthur explores the moments that have left him spellbound, tying his own experiences as a young boy from Ulster who saw his first hummingbirds in London to the wonder felt by early settlers to America who sent pressed hummingbirds across the ocean to the communities they had left behind. Through rumination on the seemingly quotidian, Arthur’s lyrical prose exposes new layers of possibility just beneath the surface of the expected.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 160.80 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei -

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.06 lei

Preț: 166.06 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.25 lei

Preț: 170.25 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 145.35 lei

Preț: 145.35 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.50 lei

Preț: 173.50 lei -

Preț: 172.69 lei

Preț: 172.69 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 267

Preț estimativ în valută:

34.08€ • 35.45$ • 28.14£

34.08€ • 35.45$ • 28.14£

Carte tipărită la comandă

Livrare economică 10-16 aprilie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814254844

ISBN-10: 0814254845

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814254845

Pagini: 264

Dimensiuni: 140 x 216 x 18 mm

Greutate: 0.32 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad Creek Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“The voice that speaks in all his work is quiet, yet lyrical, both self-effacing and slyly self-conscious. . . . [W]hat Chris Arthur has done here is show us, in the pressing of his thoughts to paper, how the individual life takes flight each time we snatch it from the air and stamp it to the page.” —Northwords Now

“In Chris Arthur’s masterful, elegant essay collection Hummingbirds Between the Pages, expansive and granular meditations on time, language, nature, mortality, and Northern Ireland capture wonder in the everyday. . . . Through singular phrasing and meticulous descriptions, these essays return again and again to the unlikely miracle of being alive.” —Foreword Reviews

“The essay, in Chris Arthur’s hands, proclaims its outsider status, its subversive momentum, its effortless inclusivity and freedom from trammels of the imagination, attaining an embodiment which is civilized, idiosyncratic and rare.” —Times Literary Supplement

"Together these essays take on a near-cosmic view of how we got here and where we are going. It's a stunning collection that reveals a depth and nimbleness of thinking that is a joy to read." —Shelf Awareness

“Arthur is proof that the art of the essay is flourishing.” —Publishers Weekly

"Arthur is a gifted observer, and these finely crafted essays will surprise and delight." —Publishers Weekly

“Among the very best essayists in the English language today.” —Robert Atwan, founder and series editor of The Best American Essays

Notă biografică

Chris Arthur is an Irish writer whose seven previous essay collections include Reading Life, On the Shoreline of Knowledge, and Words of the Grey Wind.

Extras

How Many Words Do You Need to Describe a Woodpigeon?

Being a writer, I suppose it’s not surprising that I’m intrigued by the relationship between language and the natural world, or that I try to craft as close a fit as possible between my sentences and whatever it is I’m using them to word into being on the page. I’ve always liked the advice given by Japan’s great master of haiku poetry, Matsuo Basho (1644–1694): “Let not a hair’s breadth separate your mind from what you write.” I know how hard it is to close that hair’s breadth, but I also appreciate what a rich and flexible resource the English language is for effecting precisely this kind of closure and precision. Yet, even though I sometimes feel I’ve succeeded in saying more or less exactly what I have in mind, I know that there’s a massive disparity between the actuality of the natural world and how we express our experience of it. In fact, the way we talk—and write—about nature tends to happen at a level of such simplification, so far removed from its sumptuous complexities, that it can seem as if we’re talking about something else entirely.

Aristotle famously said that philosophy begins with wonder. I believe that responsible attitudes to the natural world have a similar point of origin. My worry is that the way in which we routinely apply language to that world may be a contributory factor leading to the mindset that allows us to wreak such damage on our environment. Verbal simplifications, and the superficial perceptions—or rather misperceptions—they foster, undermine the sense of wonder on which respect for nature is founded.

In case this all sounds too vague and abstract, let me tie these generalizations down to a specific example. It’s tempting to go for something rare, beautiful, and endangered—a snow leopard, perhaps, or a quetzal—but I think the point is better made by something more mundane. So, let’s take the woodpigeon that landed the other morning on the lawn just outside my window. Watching it strut and peck its way across the grass helped to crystallize the realization of how impoverished the verbal strategies are that we normally call into play and how often they make what’s extraordinary seem ordinary.

Woodpigeons are common birds, of course, pests in the eyes of many farmers and gardeners. From such perspectives they’re not deserving of any special use of language. Surely all that needs to be said in order to describe the moment is something like: “There’s a woodpigeon on the lawn.” What’s wrong with leaving it at that? At one level, nothing whatsoever—it provides a workable enough account in rough-and-ready terms of what happened at a certain time and place. My concern is that we too seldom recognize such statements for what they are: radical attenuations, disguised abbreviations, excerpts telling so little of the story that they only provide a massively diluted taste of the world’s flavors.

In J. A. Baker’s The Peregrine, a book which shows how language and nature can be brought into a far more potent alignment than we normally allow, the author observes that “the hardest thing of all to see is what is really there.” That comment came back to me as I tried to find a way of catching in words what was involved when the woodpigeon landed on my lawn. On reflection, the phrases I’d normally use to describe it all seemed designed to hide, rather than to see—still less to celebrate—what was really there.

The more I thought about it, all the words I normally rely on seemed badly flawed. Letting that commonsense statement “There’s a woodpigeon on the lawn” stand as representative of our ordinary diction, it was as if it encountered four waves of assault. Each wave eroded its credibility. But the impact of these waves wasn’t merely destructive; they also broke into a more encompassing vision, sweeping me towards what is, I hope, a less blinkered account than the one offered by our usual modes of discourse.

Being a writer, I suppose it’s not surprising that I’m intrigued by the relationship between language and the natural world, or that I try to craft as close a fit as possible between my sentences and whatever it is I’m using them to word into being on the page. I’ve always liked the advice given by Japan’s great master of haiku poetry, Matsuo Basho (1644–1694): “Let not a hair’s breadth separate your mind from what you write.” I know how hard it is to close that hair’s breadth, but I also appreciate what a rich and flexible resource the English language is for effecting precisely this kind of closure and precision. Yet, even though I sometimes feel I’ve succeeded in saying more or less exactly what I have in mind, I know that there’s a massive disparity between the actuality of the natural world and how we express our experience of it. In fact, the way we talk—and write—about nature tends to happen at a level of such simplification, so far removed from its sumptuous complexities, that it can seem as if we’re talking about something else entirely.

Aristotle famously said that philosophy begins with wonder. I believe that responsible attitudes to the natural world have a similar point of origin. My worry is that the way in which we routinely apply language to that world may be a contributory factor leading to the mindset that allows us to wreak such damage on our environment. Verbal simplifications, and the superficial perceptions—or rather misperceptions—they foster, undermine the sense of wonder on which respect for nature is founded.

In case this all sounds too vague and abstract, let me tie these generalizations down to a specific example. It’s tempting to go for something rare, beautiful, and endangered—a snow leopard, perhaps, or a quetzal—but I think the point is better made by something more mundane. So, let’s take the woodpigeon that landed the other morning on the lawn just outside my window. Watching it strut and peck its way across the grass helped to crystallize the realization of how impoverished the verbal strategies are that we normally call into play and how often they make what’s extraordinary seem ordinary.

Woodpigeons are common birds, of course, pests in the eyes of many farmers and gardeners. From such perspectives they’re not deserving of any special use of language. Surely all that needs to be said in order to describe the moment is something like: “There’s a woodpigeon on the lawn.” What’s wrong with leaving it at that? At one level, nothing whatsoever—it provides a workable enough account in rough-and-ready terms of what happened at a certain time and place. My concern is that we too seldom recognize such statements for what they are: radical attenuations, disguised abbreviations, excerpts telling so little of the story that they only provide a massively diluted taste of the world’s flavors.

In J. A. Baker’s The Peregrine, a book which shows how language and nature can be brought into a far more potent alignment than we normally allow, the author observes that “the hardest thing of all to see is what is really there.” That comment came back to me as I tried to find a way of catching in words what was involved when the woodpigeon landed on my lawn. On reflection, the phrases I’d normally use to describe it all seemed designed to hide, rather than to see—still less to celebrate—what was really there.

The more I thought about it, all the words I normally rely on seemed badly flawed. Letting that commonsense statement “There’s a woodpigeon on the lawn” stand as representative of our ordinary diction, it was as if it encountered four waves of assault. Each wave eroded its credibility. But the impact of these waves wasn’t merely destructive; they also broke into a more encompassing vision, sweeping me towards what is, I hope, a less blinkered account than the one offered by our usual modes of discourse.

Descriere

An acclaimed writer’s ruminations on the layer beneath life’s quotidian moments, from Darwin to Buddha and back.