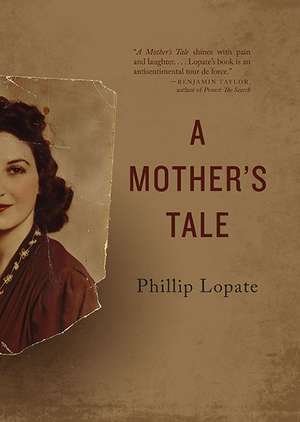

A Mother’s Tale: 21st Century Essays

Autor Phillip Lopateen Limba Engleză Hardback – 15 ian 2017

In 1984, Phillip Lopate sat down with his mother, Frances, to listen to her life story. A strong, resilient, indomitable woman who lived through the major events of the 20th century, she was orphaned in childhood, ran away and married young, then reinvented herself as a mother, war factory worker, candy store owner, community organizer, clerk, actress and singer. But paired with exciting anecdotes are the criticisms of the husband who couldn’t satisfy her, the details of numerous affairs and sexual encounters, and though she succeeded at many of her roles, Fran always felt mistreated, taken advantage of. After the interviews, at a loss for what to do with the tapes, Lopate put them away. But thirty years after, after his mother had passed away, Lopate found himself drawn back to the recordings of this conversation, and thus begins a three-way conversation between a mother, his younger self, and the person he is today. Trying to break open the family myths, rationalizations, and self-deceptions, A Mother’s Tale is about family members who love each other but who can’t seem to overcome their mutual mistrust. Though Phillip is sympathizing to a point, he cannot join her in her operatic displays of self-pity and her blaming his father for everything that went wrong. His detached, ironic character has been formed partly in response to her melodramatic one. The climax is an argument in which he tries to persuade her, using logic, of all things, that he really does love her, and is only partially successful, of course. A Mother’s Tale is about something primal and universal: the relationship between a mother and her child, the parent disappointed with the payback, the child, now fully grown, judgmental. The humor is in the details.

Din seria 21st Century Essays

-

Preț: 144.33 lei

Preț: 144.33 lei -

Preț: 108.17 lei

Preț: 108.17 lei -

Preț: 140.55 lei

Preț: 140.55 lei -

Preț: 111.26 lei

Preț: 111.26 lei -

Preț: 105.16 lei

Preț: 105.16 lei -

Preț: 112.49 lei

Preț: 112.49 lei -

Preț: 106.20 lei

Preț: 106.20 lei -

Preț: 166.05 lei

Preț: 166.05 lei -

Preț: 127.45 lei

Preț: 127.45 lei -

Preț: 108.03 lei

Preț: 108.03 lei -

Preț: 140.47 lei

Preț: 140.47 lei -

Preț: 103.91 lei

Preț: 103.91 lei -

Preț: 155.05 lei

Preț: 155.05 lei -

Preț: 147.11 lei

Preț: 147.11 lei -

Preț: 145.96 lei

Preț: 145.96 lei -

Preț: 174.52 lei

Preț: 174.52 lei -

Preț: 178.10 lei

Preț: 178.10 lei -

Preț: 148.67 lei

Preț: 148.67 lei -

Preț: 170.24 lei

Preț: 170.24 lei -

Preț: 132.52 lei

Preț: 132.52 lei -

Preț: 176.88 lei

Preț: 176.88 lei -

Preț: 143.44 lei

Preț: 143.44 lei -

Preț: 144.05 lei

Preț: 144.05 lei -

Preț: 148.41 lei

Preț: 148.41 lei -

Preț: 149.08 lei

Preț: 149.08 lei -

Preț: 166.85 lei

Preț: 166.85 lei -

Preț: 173.49 lei

Preț: 173.49 lei -

Preț: 172.68 lei

Preț: 172.68 lei -

Preț: 103.72 lei

Preț: 103.72 lei -

Preț: 119.18 lei

Preț: 119.18 lei -

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 104.95 lei

Preț: 160.80 lei

Nou

Puncte Express: 241

Preț estimativ în valută:

30.77€ • 32.12$ • 25.47£

30.77€ • 32.12$ • 25.47£

Carte disponibilă

Livrare economică 15-29 martie

Preluare comenzi: 021 569.72.76

Specificații

ISBN-13: 9780814213315

ISBN-10: 0814213316

Pagini: 200

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad River Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

ISBN-10: 0814213316

Pagini: 200

Dimensiuni: 152 x 229 x 20 mm

Greutate: 0.43 kg

Ediția:1

Editura: Ohio State University Press

Colecția Mad River Books

Seria 21st Century Essays

Recenzii

“I relished this book. From its clash between mother and son emerges a fortifying love, which (I guess like all parental love) has its casualties along with its lush victories.” —Richard Ford

“The gravitational pull of the child toward the mother is so powerful that it persists even in the face of cruelty or neglect. What is finally most affecting about this book is not Frances’s story but her son’s pained efforts to confront it.” —Ruth Franklin, The New York Review of Books

"[A] fascinating and deftly constructed book." —Jerald Walker, The New York Times Book Review

“Lucky for us, the cassettes collected dust in a shoebox in the closet until he was ready to write this entertaining and moving book, which is equal parts reflection, reconstruction, police interrogation, psychiatric evaluation, and, ultimately, tribute to his mother.” —Annabelle Gurwitch, Los Angeles Review of Books

“By offering readers a candid portrait of his mother, Lopate manages precisely what he must: he takes a personal story and turns it outward, and in doing so, he makes it our story, too.” —B. J. Hollar, The Los Angeles Review

“Lopate, who’s made a life out of language, listens back to the woman who first taught him to speak.” —Hayden Bennett, San Francisco Chronicle

“A Mother’s Tale is a nonfiction book that gives Frances a lot of time in the spotlight. . . . Lopate’s mother was a ‘monologist’ who understood the power of narrative, and a person who could captivate and frustrate any audience who was willing to listen to her.” —Michele Filgate, Barnes & Noble Review

“A Mother’s Tale shines with pain and laughter. . . . Lopate’s book is an antisentimental tour de force.”—Benjamin Taylor, author of Proust: The Search

Notă biografică

Phillip Lopate is a central figure in the resurgence of the American essay and the author of The Art of the Personal Essay, Bachelorhood, and Against Joie de Vivre, among others. He is a professor in the graduate nonfiction program at Columbia University.

Extras

Above and beyond any attempt to reach the truth, I know that transcribing these tapes and writing my responses to them has been an attempt to keep my mother “alive” for as long as possible, to get her off the gurney, to hear her voice again, and, in this way, to bring her back to life.

So, in a strange way, we have come full circle: I began by telling about my mother’s futile effort to call out to her father so forcefully as to deter him from passing into the shades, and now here I’ve been doing much the same thing, trying to summon her back from the underworld, largely by quoting her, with the quixotic hope that she will be pleased enough by the sound of her voice to re-emerge, however fleetingly.

Hearing these tapes again was a shock. Her voice filled the room where I write, just as strong and confident as it had always been. At times the things she said were so shocking, I would have to pause the tape and sit there, gasping. Uncle Morris? Really? And when it came to the argument near the end, when I tried to convince her that I did love and care about her, I was flabbergasted, sweating, as though I were still defending my life. Her voice was the original Other, but it was also a part of me. As a baby I had first learned human speech from listening to her, and as a child I had internalized that voice to such an extent that it was hard to say where she left off and my own voice began. That writing voice from which I take dictation, and of which I am so proud, started out being hers. (I still hear her in my head, sixteen years after her death. I don’t hear my father anymore because he was so silent, but when I look in the mirror I see him, especially when I don’t smile—that same grim, stern expression.)

Listening to and transcribing these tapes, I was impressed by the sweep of my mother’s life—all this woman had gone through. Born to European immigrants into in a comfortable middle-class home, she was her parents’ favorite but lost them at such an early age. She was raised by strict, indifferent siblings, a runaway and high school dropout. She was forced to reinvent herself over and over: working at a beauty parlor, becoming a housewife and a mother, running a candy store, working in war factories, starting a photography business and a camera store, clerking for garment companies, going into show business, touring America, doing commercials, going back to school. . . . It was a twentieth century life. Born in 1918, died in 2000, she began to seem to me representative of millions of women who had passed through the same time period: the end of World War I, the Depression, the New Deal, World War II, the Korean War, the civil rights movement, Vietnam and the antiwar movement, gay rights, feminism. Her very discontent seemed emblematic of millions of other women’s experiences, or so I have told myself, while working on this book, trying to quiet the carping voice that said: Who’s going to care about your mother enough to want to read it?

I am well aware that if I had transformed this account into my own prose, it might have read more smoothly, more palatably. My mother could exasperate or get on a reader’s nerves, just as she sometimes did on mine. But I opted for large sections of the transcribed tapes, more or less verbatim, because they graphically showed, to me at least, how one edges toward an insight and then backs away, how we rationalize or shift the blame onto others. I chose to include so much of her testimony verbatim because it seemed a more realistic presentation of the person she was, and the dynamic between us. (Realism, that old, disabused deity.) So yes, there is a scientific streak in me that is curious about the way people talk, and that would be inclined to diagram interactional patterns. The tapes also showed, in spite of the love and goodwill between us, how the wariness between a parent and a grown child might not overcome a certain impasse. The stalemate between us was unbreakable: we were too much alike. When I showed an earlier draft of this manuscript to someone, he was dismayed that there seemed to be no change in my views of my mother from my earlier self to my present one—no softening. This is true. I would have been happy to demonstrate some eureka, some redemptive insight that deepened or warmed my feelings, but in truth there was no On Golden Pond moment during her lifetime when we fell into each other’s arms, and since she is gone I have not found it any easier to embrace her ghost. I was raised by a powerful woman, and the defenses I developed against her have not essentially altered, any more than have the admiration, gratitude, and fascination I feel for her.

So, in a strange way, we have come full circle: I began by telling about my mother’s futile effort to call out to her father so forcefully as to deter him from passing into the shades, and now here I’ve been doing much the same thing, trying to summon her back from the underworld, largely by quoting her, with the quixotic hope that she will be pleased enough by the sound of her voice to re-emerge, however fleetingly.

Hearing these tapes again was a shock. Her voice filled the room where I write, just as strong and confident as it had always been. At times the things she said were so shocking, I would have to pause the tape and sit there, gasping. Uncle Morris? Really? And when it came to the argument near the end, when I tried to convince her that I did love and care about her, I was flabbergasted, sweating, as though I were still defending my life. Her voice was the original Other, but it was also a part of me. As a baby I had first learned human speech from listening to her, and as a child I had internalized that voice to such an extent that it was hard to say where she left off and my own voice began. That writing voice from which I take dictation, and of which I am so proud, started out being hers. (I still hear her in my head, sixteen years after her death. I don’t hear my father anymore because he was so silent, but when I look in the mirror I see him, especially when I don’t smile—that same grim, stern expression.)

Listening to and transcribing these tapes, I was impressed by the sweep of my mother’s life—all this woman had gone through. Born to European immigrants into in a comfortable middle-class home, she was her parents’ favorite but lost them at such an early age. She was raised by strict, indifferent siblings, a runaway and high school dropout. She was forced to reinvent herself over and over: working at a beauty parlor, becoming a housewife and a mother, running a candy store, working in war factories, starting a photography business and a camera store, clerking for garment companies, going into show business, touring America, doing commercials, going back to school. . . . It was a twentieth century life. Born in 1918, died in 2000, she began to seem to me representative of millions of women who had passed through the same time period: the end of World War I, the Depression, the New Deal, World War II, the Korean War, the civil rights movement, Vietnam and the antiwar movement, gay rights, feminism. Her very discontent seemed emblematic of millions of other women’s experiences, or so I have told myself, while working on this book, trying to quiet the carping voice that said: Who’s going to care about your mother enough to want to read it?

I am well aware that if I had transformed this account into my own prose, it might have read more smoothly, more palatably. My mother could exasperate or get on a reader’s nerves, just as she sometimes did on mine. But I opted for large sections of the transcribed tapes, more or less verbatim, because they graphically showed, to me at least, how one edges toward an insight and then backs away, how we rationalize or shift the blame onto others. I chose to include so much of her testimony verbatim because it seemed a more realistic presentation of the person she was, and the dynamic between us. (Realism, that old, disabused deity.) So yes, there is a scientific streak in me that is curious about the way people talk, and that would be inclined to diagram interactional patterns. The tapes also showed, in spite of the love and goodwill between us, how the wariness between a parent and a grown child might not overcome a certain impasse. The stalemate between us was unbreakable: we were too much alike. When I showed an earlier draft of this manuscript to someone, he was dismayed that there seemed to be no change in my views of my mother from my earlier self to my present one—no softening. This is true. I would have been happy to demonstrate some eureka, some redemptive insight that deepened or warmed my feelings, but in truth there was no On Golden Pond moment during her lifetime when we fell into each other’s arms, and since she is gone I have not found it any easier to embrace her ghost. I was raised by a powerful woman, and the defenses I developed against her have not essentially altered, any more than have the admiration, gratitude, and fascination I feel for her.